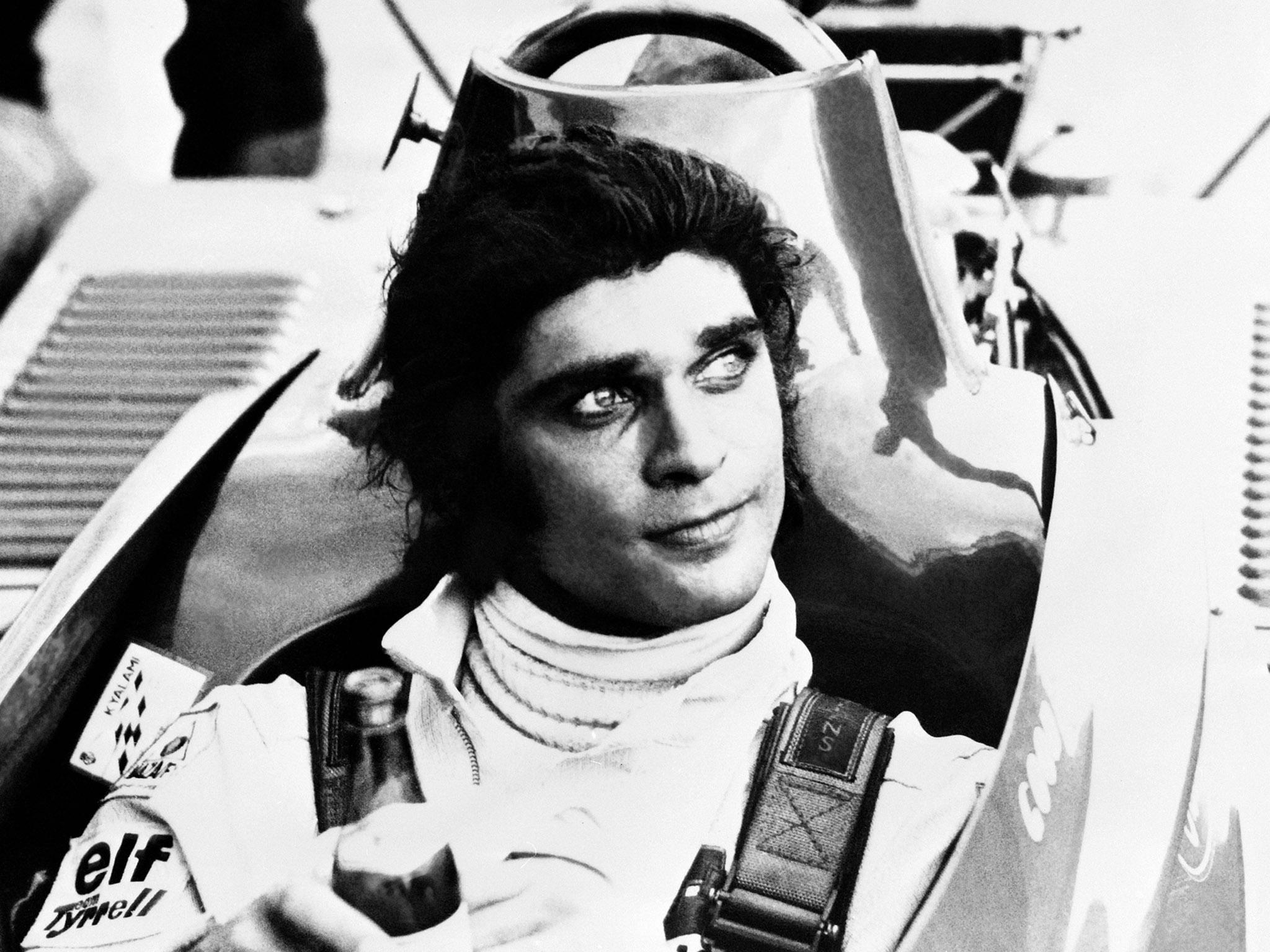

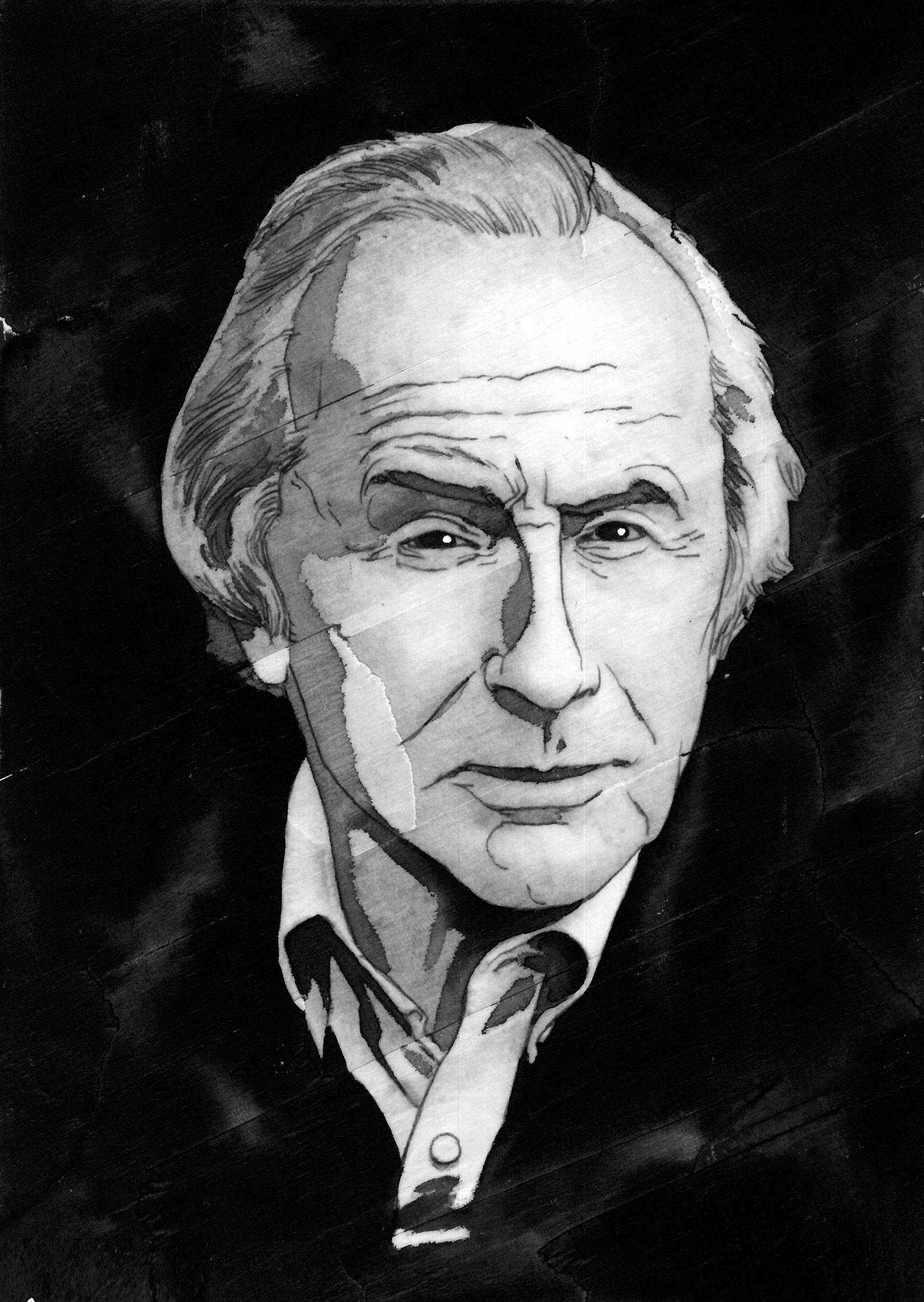

Sir John Young Stewart is one of the all-time motor racing greats. A three-time Formula One world champion, Jackie Stewart’s career statistics make for quite incredible reading. In his 99 starts he finished on the podium in more than 40 per cent of the races he ran. His win ratio sat just shy of one in three. He was the master of his craft and the king of Formula One in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Born in Milton, Dunbartonshire, Scotland, in 1939, he had dyslexia – undiagnosed at that time – and was forced to leave school at 16, when he went to work in his father’s garage as a mechanic. In 1965 he joined Formula One full time with BRM and finished third in the World Championship. Eventually he rejoined Tyrrell, taking the team’s Matra-Ford to glory in 1969. In 1971 he raced Tyrrell’s own car to a second title and repeated the feat again in 1973, all the while competing around the world in disciplines as varied as the Le Mans 24 Hours, European Touring Car Championship, Can-Am and the Indy 500.

But while Stewart is known and revered as one of the great racing drivers of his age, he is perhaps equally respected for the tireless work and campaigning he undertook to advance driver safety. After an accident in the 1966 Belgian Grand Prix had left him trapped in his car with fuel leaking all around him and no safety crews to extract him from his perilous situation, he took it upon himself to lead what, at times, was a lonely and much-derided campaign. He pushed for the modernisation of circuits, the fitting of barriers and run-off, the advancement of medical facilities, and trained, well-equipped marshals. When it was called for, he led driver boycotts.

His work and the foundations he established have, over the nearly five decades since his retirement, saved the lives of countless drivers the world over. Yet for all of his labour and all of his achievements in the realm of racing safety, the cruellest twist unfurled on what was to be his final ever racing weekend.

Jackie Stewart explains: “In April 1973 I decided that I would retire from Formula One at the end of the season. I was quite comfortable and happy to do so, partly because the last race of the season, the US Grand Prix at Watkins Glen, would have been my 100th race. By the time it came around in October I had already secured my last world championship at Monza in September.

“On the Saturday of what would have been my 100th and final grand prix, my team-mate Francois Cevert was killed in front of us drivers. The accident occurred at a very quick part of the race track. The amount of debris on the circuit was enormous. I thought, my God, what a huge accident. The yellow flags were out, all the cars had to stop because the debris was so extreme on the track. Every driver had obviously got out of their car and had gone to see if they could help, and I was the last to arrive. So I got out of my car and went over to where the rest of the car was. It was a terrible sight and Francois was equally in terrible shape. It was obvious that he was already dead.

“So from, if you like, the euphoria of winning the World Championship, the euphoria of knowing that I was never going to race again, suddenly the last race of my career ended in the worst possible way. It was the worst sight I’ve ever seen in my life. My motor racing career has a lot of high points and a lot of bad points because so many people were killed during that period. Jochen Rindt was killed, Jim Clark, Francois, Piers Courage… and in those days they never stopped the race.

“So even with all the high moments and great moments in my career, these events were horrendous. The current generation wouldn’t understand any of that sort of stuff. The only way I can relate to it, thinking back, is that it must have been like World War Two and the Spitfires and Hurricanes leaving the south coast of England to stop the German Luftwaffe getting to London. They were losing their colleagues on a regular basis. And so were we.”

Will Buxton: After Francois was killed, did you ever get the ability to put yourself back into that situation? Where you could just switch off the emotion and get into that place of calm tranquillity that only comes behind the wheel of a racing car? And if not, how did you deal with the emotion of it all?

Jackie Stewart: “No. I never did again. But it was happening so often that we were used to death. I must have gone to more funerals than any person I know. If Helen and I were at home, now, and we saw the movie of that accident, we’d still be in tears and still be affected by it today. It doesn’t go away. It was such a deep experience.

“Helen and I once counted 57 people that had lost their lives in racing, not just in Formula One. It was the Swinging Sixties, of course, and we joke nowadays that in those days motor racing was dangerous and sex was safe. Racing drivers in those days had an ability, whether it was Graham Hill or Jack Brabham or Chris Amon, to switch off. We were a different animal because we were living with it so regularly. You could say you were being emotionless, but that’s not true. We just dealt with it in different ways.

“But my quest for safety had become by far the most unpopular thing that I was faced with. I don’t think there’s a single corner of any race track in the world called Stewart corner. The organisers, the governing body and the track owners were so angry that somebody who happened to be the world champion was saying that we were not going to race at the Nürburgring or Spa, two of the greatest and most demanding race tracks in the world. If somebody asked me what the best lap I ever drove was, it would be the Nürburgring. Spa wasn’t far behind it.”

“But the organisers wouldn’t do anything. They wouldn’t do one thing. I was chairman and president of the Grand Prix Drivers’ Association, and different drivers were chosen to do track inspections. Jim Clark was killed at Hockenheim the day that I was doing the inspection at Jarama, where the Spanish Grand Prix was held at that time. Jochen did the Nürburgring track inspection because he spoke German, but they wouldn’t do one single thing on that 23km track of 160 or so corners. Not one thing. They said if they made one change then we’d want another and another, so they said no to everything. So, we had no choice. We banned the Nürburgring.”

Now, can you imagine how unpopular that was? Jackie Stewart was not by any means welcome to any track in the world, because they were always worried about what we’d come up with next. We cancelled Spa, which was the second most respected track in the world. They said they’d run the Belgian race at Zolder instead, but when we went there the track surface was breaking up. We told them they had to resurface during the night and they did it. In those days we had such power, because of the deaths that were happening. The Grand Prix Drivers’ Association was a very powerful group, not like today.”

Will Buxton: In retirement, did you redouble your efforts on safety?

Jackie Stewart: “No. I didn’t think it was my job after I retired. I thought it should be the people who were driving the cars. I thought they were the best authorities, so I never continued that. The governing body wouldn’t have wanted me to either. It’s why I make the point about corner names. I think there is a grandstand named after me in Melbourne. But my safety work had made me very unpopular.

“For 44 years I was the winningest driver in the United Kingdom, but there’s no Stewart corner at Brands Hatch or Silverstone or Oulton Park or even Snetterton. I was the man who was up front, demanding things that were costing money which wasn’t available at the time. I understand that. But we couldn’t have gone on racing as we were. The insurance companies would have stopped it eventually. We didn’t have any facilities to avoid another catastrophe like we’d had even as far back as Le Mans in 1955, where 83 spectators were killed.

“Thank God the current generation don’t have to face the kind of things that we faced. The mood on a starting grid today is totally different than the mood on a starting grid in the 1960s and early 1970s. So many people were losing their lives that there was a different attitude. Nowadays it is fairly relaxed.”

“Eventually Sid Watkins and Max Mosley together continued that work to where we see it today. I think the sport today is fantastic, and it is so safe that, oddly, it is almost too safe. The drivers are permitted to make mistakes today that they could not have made in past years. They’re a lot more flippant today than they were in those days. They can go off the track and there’s run-off areas, and if they go far enough and hit something it is a deformable structure. The cockpit and the survival cell is an incredible thing. The head and neck safety device is brilliant. It is a whole different world. But the camaraderie and the relationships we had back then were fantastic. We holidayed together, we travelled together, the whole atmosphere was totally different.”

Will Buxton: And, I guess, through it all, the one constant, your wife, Helen?

Jackie Stewart: “Helen went through the whole thing. I married her when I was a clay pigeon shooter. She was fantastic. She never once asked me to stop racing, even after all the deaths. In those days the wives were as close to each other as we were. They had a circle called the Dog House Club where they’d all go and have cups of tea when we were with the engineers. We’d always make sure they had a room at the track where they could set up this club; Bette Hill, Helen and all the wives all together. So when one of the drivers was killed, all the other wives had to look after each other. Helen had to look after Nina when Jochen was killed, Sarah when Piers was killed… and she looked after me, too.

“But to have to go and pack the bags of somebody who had just been killed, because their wife couldn’t stand to go back to the hotel room, well Helen had to do that so many times. She went with so many of the wives to the hospital, helping them all in their moment of absolute grief, while I was still driving around in circles. She was so strong.”

Will Buxton: Do you think the death of Francois affected you so much because of the unfulfilled potential?

Jackie Stewart: “I don’t think so. It was just the worst thing that could have happened at that time. It was as if God had said, ‘You’ve had everything, you’ve done everything, you’ve got everything, you’ve won your world championships and you have all the money in the world and everything you want’, and it was as if he’d turned around and clicked his fingers at that moment and said, ‘But don’t you dare take anything for granted’. Francois’ death was the worst thing that could have happened.”

Will Buxton: Do you still think about him?

Jackie Stewart: “Oh, sure. He’s sitting on the left-hand side of the fireplace. I think about him all the time.”

Extracted from My Greatest Defeat by Will Buxton (Evro Publishing); www.evropublishing.co.uk; £19.99, out now

Sir Jackie Stewart is the founder of Race Against Dementia, a charity established to fight against the as yet incurable disease that his beloved wife, Lady Helen, suffers from. It is an illness that will affect one in three of us. For more information, please visit www.raceagainstdementia.com