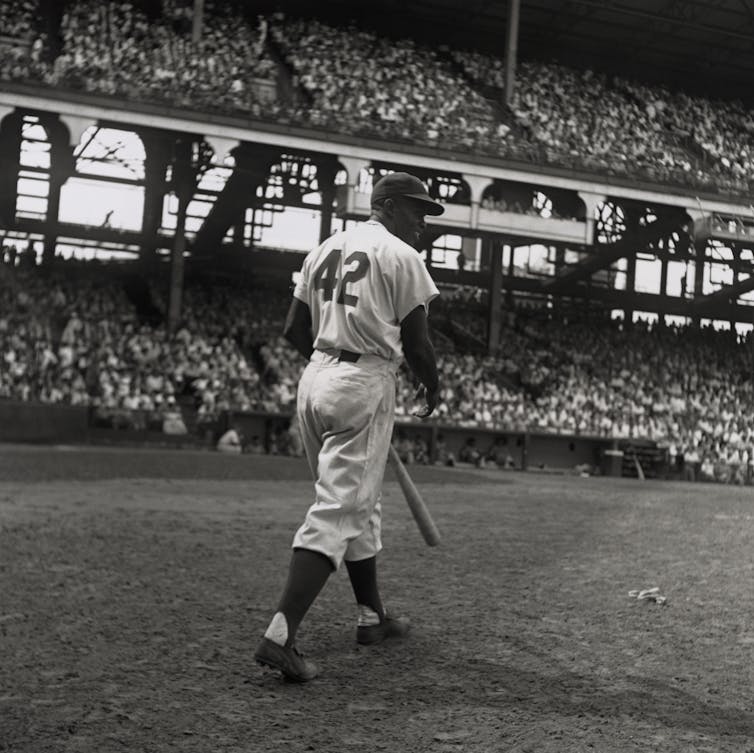

On April 15, 1947, Jackie Robinson played his first game with the Brooklyn Dodgers, forever changing baseball and society.

Robinson was Black, and the integration of all-white major league baseball was perhaps the most important story about civil rights in the years immediately following World War II.

The integration, Jules Tygiel wrote in his groundbreaking book “Baseball’s Great Experiment,” “captured the imagination of millions of Americans who had previously ignored the nation’s racial dilemma.”

As Martin Luther King Jr. famously put it, Robinson “was a sit-inner before sit-ins, a freedom rider before freedom rides.”

Major League Baseball celebrates the 75th anniversary of Robinson’s historic career on April 15, 2022, in stadiums and ballparks across the nation.

But in my view, those celebrations will fall short if they don’t address how Robinson confronted white supremacy with class and dignity during a time before he joined the Dodgers, when his own minor league manager once asked, “Do you really think a nigra is a human being?”

I’ve written or edited four books about Jackie Robinson. When I give a lecture or a talk about him, I often mention that he was a Republican.

Given the modern-day opposition that the Republican Party has toward civil and voting rights protections – and the teaching of racism in American history – this invariably provokes an audible gasp from the audience.

Republican roots

Robinson, who lived from 1919 to 1972, was a Republican when millions of other Blacks were Republicans.

Back in those days, the GOP still hung on to its mantra that it was “the party of Abraham Lincoln,” the president who signed the Emancipation Proclamation.

The proclamation declared “that all persons held as slaves” within the rebellious Southern states that had seceded from the Union “are, and henceforward shall be free.”

Robinson’s parents gave him the middle name Roosevelt in honor of Republican President Teddy Roosevelt, “who expressed disdain about racism,” Arnold Rampersad wrote in his Robinson biography, “before white supremacist power made Roosevelt retreat into conservatism.”

Branch Rickey, the white Dodgers executive who signed Robinson to a contract and became his mentor, was an ardent Republican who believed in racial equality. Robinson supported and then worked for civil rights advocate New York Gov. Nelson Rockefeller.

“If we had one or two governors in the Deep South like Nelson Rockefeller,” King said, “many of our problems could be readily solved.”

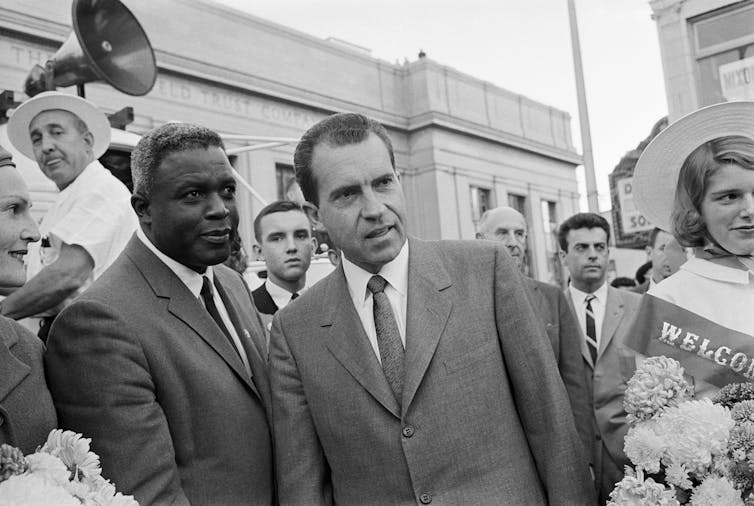

Robinson endorsed Richard Nixon, the Republican candidate for president, in 1960. Nixon, who, like Robinson, was from southern California, convinced Robinson, a former UCLA athlete, that he would support civil rights.

Robinson found Democratic presidential candidate John F. Kennedy, Nixon’s opponent, “insincere” in his tepid support for civil rights.

Kennedy won the presidential election that year.

The white man’s party

In 1964, U.S. Sen. Barry Goldwater of Arizona challenged Rockefeller and other more liberal Republicans for control of what the right wing called “the white man’s party.” He won the party’s presidential nomination.

Though Goldwater lost the presidential election in a landslide to Democratic President Lyndon Baines Johnson, he won the hearts and minds of pro-segregation Democrats, the mostly Southern politicians and their followers who had abandoned the Democratic Party when it endorsed legislation during the late ‘50s and '60s to advance civil rights and voting rights for Blacks.

Those who switched parties included U.S. Sen. Strom Thurmond of South Carolina, who ran for president in 1948 as a segregationist and later filibustered for more than 24 hours to prevent passage of the 1957 Civil Rights Act.

Goldwater, Nixon and others in the GOP used what they called the “Southern strategy” to leverage the grievances and fears of Southern whites over the Democrats’ groundbreaking proposal that Blacks should have equal rights.

By 1968, Robinson was done with the GOP. He refused to support Nixon when he ran for president again in 1968. He also became more active in the civil rights movement and appeared with King on frequent occasions.

Robinson also became a prolific writer, including a column for the Amsterdam News, a weekly Black newspaper, where he further developed his fierce opposition to the Republican Party.

“I suspect that unless the party showed a desire to win our votes,” he wrote in a letter 1968 to Clarence Lee Towns Jr., the leading Black member of the Republican National Committee, “it may rest assured that I and my friends cannot and will not support a conservative.”

Instead, Robinson supported Nixon’s Democratic rival, Hubert Humphrey. “I have my right to remember that I am Black and American before I am Republican,” Robinson wrote in the Amsterdam News. “As such, I will never vote for Mr. Nixon.”

When Nixon won the election, Robinson demonstrated the determination he showed throughout his life.

In one of his last letters to the Nixon White House, Robinson pleaded with special assistant Roland L. Elliott to listen to Black America before racial tensions got out of control.

“Black America has asked so little,” Robinson wrote, “but if you can’t see the anger that comes from rejection, you are treading a dangerous course. We older blacks, unfortunately were willing to wait. Today’s young blacks are ready to explode.”

On Nov. 24, 1972, Robinson died of a heart attack at age 53. Twenty-five years later, Major League Baseball honored him by retiring his number, 42, meaning the number can no longer be worn by any player in the league.

No other baseball player has been given such an honor.

Chris Lamb does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.