He was his own man, Jack Charlton, a rugged, irascible maverick who scaled unexpectedly rarefied heights as a late-developing footballer, then matured into a charismatic international manager who was practically canonised by his adoptive nation.

As a feistily combative defender he won deathless renown for joining his more famous brother, Bobby, in the England team which lifted the World Cup in 1966, and for his deeds as a colossal cornerstone of Don Revie’s magnificent Leeds United side.

As a boss he earned a second slot in soccer folklore by transforming the Republic of Ireland from attractive but lightweight underachievers into a mighty and much-feared force.

Yet arguably, it is as one of the game’s most colourful characters that Charlton will be remembered most vividly. Earthy and impetuous, cantankerous and tactless, even downright fearsome, he could be all of these things. But he could be wryly, engagingly funny, too, and his honesty was a byword.

Everything about Big Jack was distinctive: the gawky, giraffe-like frame; the rich northeastern tones which could shift from lilting to abrasive in the same sentence; the implacable, take-me-as-I-am personality.

Despite bruising plenty of egos along the way, he remained widely liked and almost universally respected, both within football and, increasingly as his cult-heroism spread, outside it, too.

That stature had been earned the hard way by a lifetime of achievement which had humble origins as the eldest of a miner’s four sons in the enormous pit village of Ashington, just up the road from Newcastle.

Charlton was a member of the footballing Milburn clan – one uncle was the England star, Jackie Milburn, and three more played for League clubs – and his mother, Cissie, was mad about the game.

She it was who coached her sons, her husband not being a soccer man, and quickly it became evident that Bobby, the second-born, was the one imbued with rare natural talent.

Even so Jack, always a strong-willed, tough, adventurous boy, grew into a useful player but spurned an early approach from Leeds because he didn’t want to leave the area and accepted a mining job.

Eventually he quit the pit, having a burning desire to make more of his life, and was on the verge of applying to join the police when Leeds made a second, successful offer.

Tall, bony and unremittingly hard, Charlton was a natural centre-half, commanding in the air and not as clumsy with the ball at his feet as his ungainly gait implied. However, after making his senior debut in 1953, he found himself in the intimidating shadow cast by John Charles, then emerging as one of the world’s finest players.

Fortunately for Charlton, the Welsh giant was deployed frequently as a centre-forward and the young northeasterner became established as first-choice stopper in 1955-56, helping Leeds secure promotion to the top flight.

Then Charles succumbed to the lure of the lira, joining Juventus in 1957, and the younger man’s career – boosted by an appearance for the Football League that year – was expected to blossom. Instead, with a perversity which was to become typical, it marked time, being marred by a series of petty but turbulent clashes with several Elland Road bosses.

A brief spell as captain did not help him and he made clear his desire to leave by causing further ructions, particularly after Leeds were relegated in 1960. He came close to joining Manchester United, then Liverpool, but no move materialised and he returned to work under the Yorkshire club’s new manager, Don Revie.

For a time the problems continued, with uneven performances, endless arguments and disruptive tantrums – on one occasion Charlton hurled a teacup which narrowly missed his boss and shattered against a wall.

Revie tried everything to get the best from his talented but tiresome troublemaker. He dropped him, played him at centre-forward, even offered him for transfer, until in 1963, with Charlton aged 29 and Leeds teetering disturbingly close to the brink of the Third Division, the manager read the riot act one final time.

The burden of Revie’s desperate address was that if Charlton went on doing things his way, soon he would be out of the game; alternatively, if he transformed his attitude, there was no reason why he shouldn’t play for England. That seemed a bit steep but, having persuaded Charlton to accept a new regime encompassing discipline and concentration, the Leeds boss was proved correct within two years.

For all his rebelliousness, Big Jack was an intelligent fellow who had already earned his own coaching qualifications, and Revie’s inspired urgings made sense. Accordingly Charlton knuckled down to improve his own performances and embrace team tactics, with spectacular results.

Meshing effectively with fellow defensive bulwark Norman Hunter, he became a key figure in the team which won the Second Division title in 1964, finished as runners-up in both the League Championship race (to Manchester United) and the FA Cup Final (to Liverpool) the following season, and then grew into one of the most compelling combinations since the war.

That Leeds team, in which midfielders Billy Bremner and Johnny Giles were the star performers, was a classic fusion of bone-crunching aggression and silky skill, and really they should have picked up even more honours than they did.

As it was their haul, during Charlton’s Elland Road sojourn, was impressive enough. There were league titles in 1969 and 1971, the FA Cup in 1972, the League Cup in 1968, the Inter Cities Fairs Cup in 1968 and the Uefa Cup in 1971.

There were other near misses in the league and defeats in finals, too, before his epic 20-year playing career ended, marginally short of his 38th birthday, after nearly 800 appearances for Leeds.

But even those exceptional accomplishments were dwarfed by developments on the international front. In 1965 Charlton had been called to his country’s colours for the first time, he and Bobby becoming the first pair of brothers to play together for England in the twentieth century.

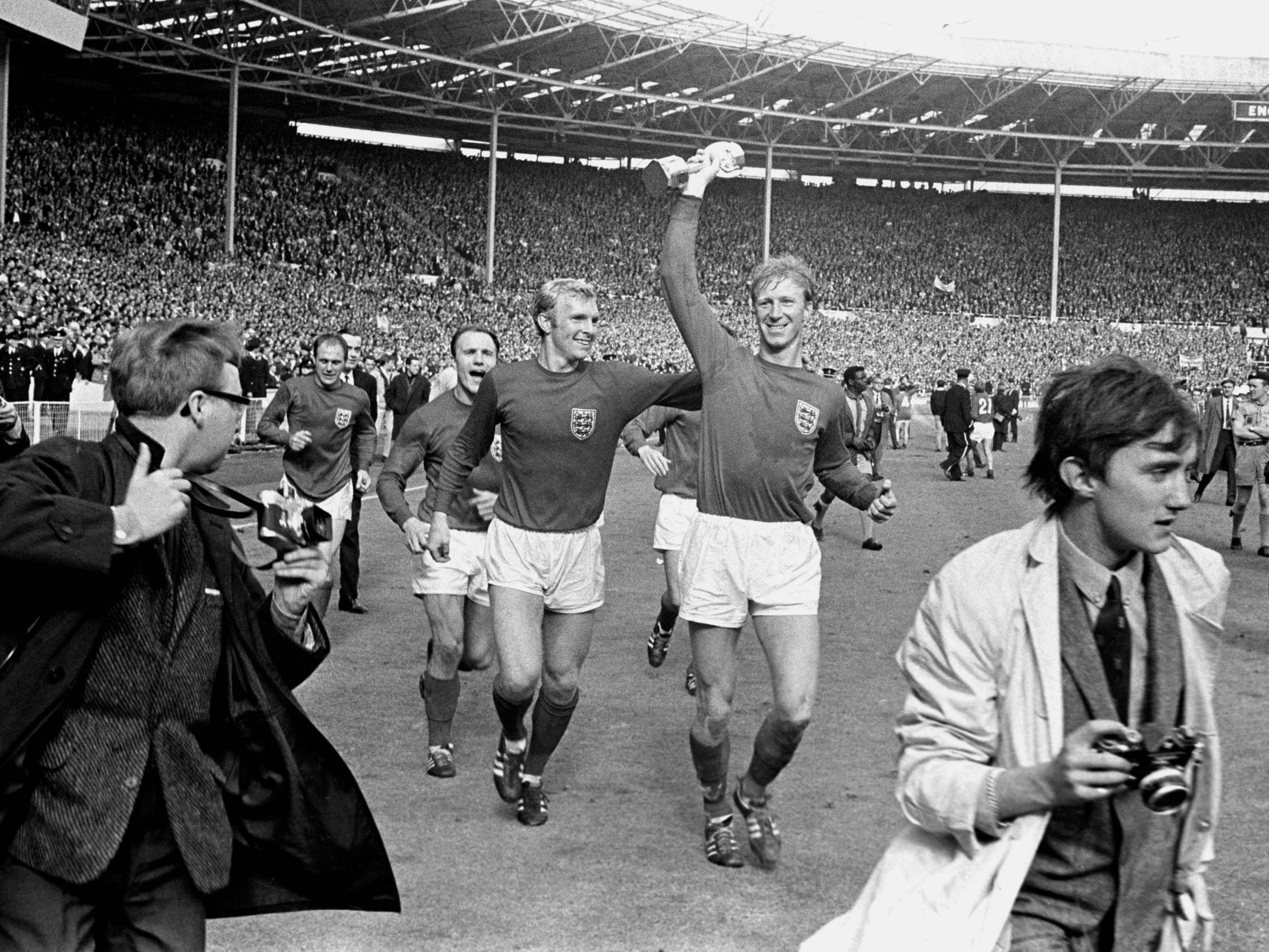

He did well and under the sage guidance of Alf Ramsey he cemented his place, reaching the ultimate pinnacle of his profession when his inspirational dominance helped England to beat West Germany in the World Cup final in 1966.

For many observers, one enduring image of that remarkable afternoon is of the elder Charlton sinking exhausted to his knees when the final whistle blew, a fitting emblem of the work ethic which was integral to Ramsey’s success.

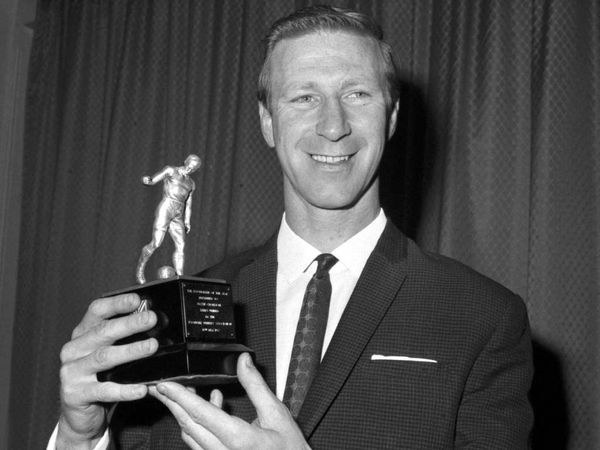

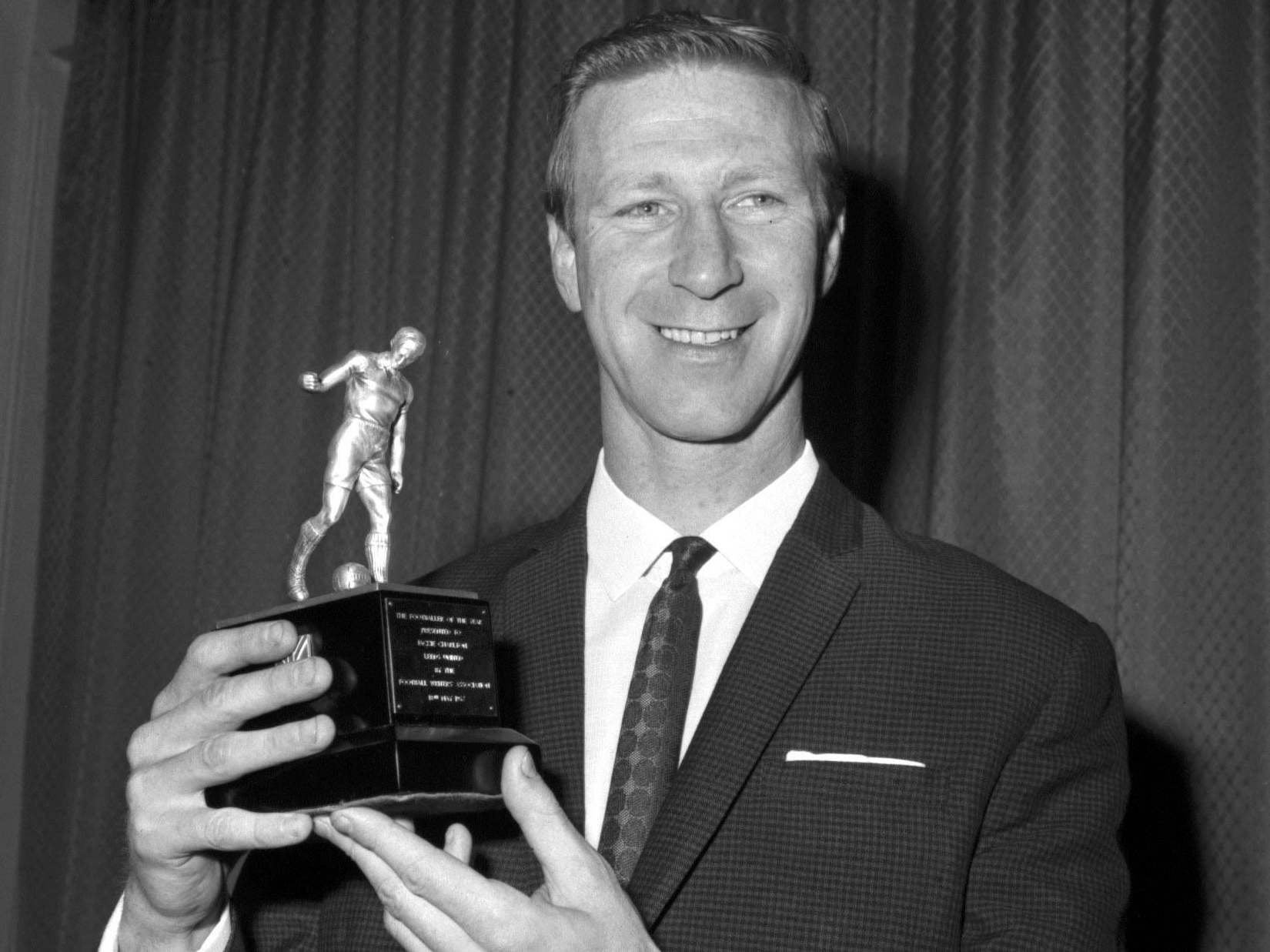

Now Jack Charlton was a celebrity, and in his own gruff, laconic way, he relished it. In 1967 he succeeded his brother as the Football Writers’ Association Footballer of the Year and went on to garner 35 caps before finishing against Czechoslovakia during the 1970 World Cup finals in Mexico.

Don Revie’s perception and motivational powers had been vindicated more comprehensively than even he could have dreamed.

Following his retirement as a player in 1973, Charlton moved directly into management, taking over at Second Division Middlesbrough and earning instant acclaim.

In his first season, Boro raced to the title, clinching promotion by March and eventually topping the table by a swingeing 15-point margin.

Not surprisingly, Charlton was named as manager of the year. He was acclaimed for his acumen in acquiring Scottish playmaker Bobby Murdoch on a free transfer from Celtic and for his tactical nous in employing a winger, Alan Foggon, to run at defences from midfield.

In later years, as he became noted for his employment of the sometimes practical but generally unlovely long-ball game, the tone of many pundits would change.

Charlton, who was awarded the OBE in 1974, went on to establish Middlesbrough as solid mid-table members of the top flight before resigning in April 1977, citing staleness and the need for a change.

Later that year, having been asked to apply for the vacant England job but never receiving a reply to his resultant letter, he took charge of Sheffield Wednesday, traditionally a big club but then languishing in the lower reaches of the Third Division.

Gradually, remorselessly, he pulled the Owls around, leading them to the Second Division in 1980 and missing promotion by only one point in 1982.

Then, having reached the FA Cup semi-finals of 1983 and believing he had taken the club as far as he could, he resigned in May, stating that no manager should remain at the same club for more than five years.

Next came a labour of love which was to end in trauma when, in June 1984, he became boss of Newcastle United, his boyhood favourites.

The Magpies were newly elevated to the top flight but poorly equipped for the challenge and Charlton was neither the first nor the last manager to be unsettled by the ongoing cradle of controversy that is St James’ Park.

Upset by differences with the board after a single disappointing campaign, and stung by terrace criticism, mainly over the sale of local hero Chris Waddle to Spurs, he resigned. After that he vowed never to return to club management and, despite receiving numerous offers, he didn’t.

Once more a grander stage was beckoning. In February 1986 Charlton accepted charge of the Republic of Ireland’s national side and at first, uncharacteristically, he was apprehensive about the reception he would receive as a “foreigner”.

He needn’t have bothered. Soon there blossomed a love affair with the Irish people which genuinely moved the hard-bitten Englishman and, although there were a few rows along the way, it was clear that he had found an ideal niche.

The most fundamental of the disagreements was over his tactics, which involved replacing the sweet-passing midfield approach epitomised by the lavishly gifted Liam Brady in favour of more direct methods.

This meant playing long balls in behind opposition defenders and pressurising opponents in all areas of the field. It wasn’t pretty and it upset purists such as Brady and David O’Leary – but it worked.

After losing his first game to Wales, Charlton assembled a tight-knit squad, which included numerous so-called Anglos (players drafted in under new and less stringent qualification rules) and here again was a bone of contention.

Traditionalists were perturbed by the non-Irish accents which permeated team talks, though they were delighted enough with the success which ensued.

In 1988 Charlton led the Republic to the European Championship finals in West Germany, the first major tournament they had ever reached, and beat England 1-0 in their opening fixture. From that moment he became an Irish folk hero, the team’s narrow failure to reach the semi-finals confirming his popularity.

Even giddier peaks were to follow as the Boys in Green qualified for Italia 90, during which they drew famously with England, reached the quarter-finals via a nerve-shredding penalty shoot-out victory over Romania and bowed out by the only goal to the host nation in the quarter-finals.

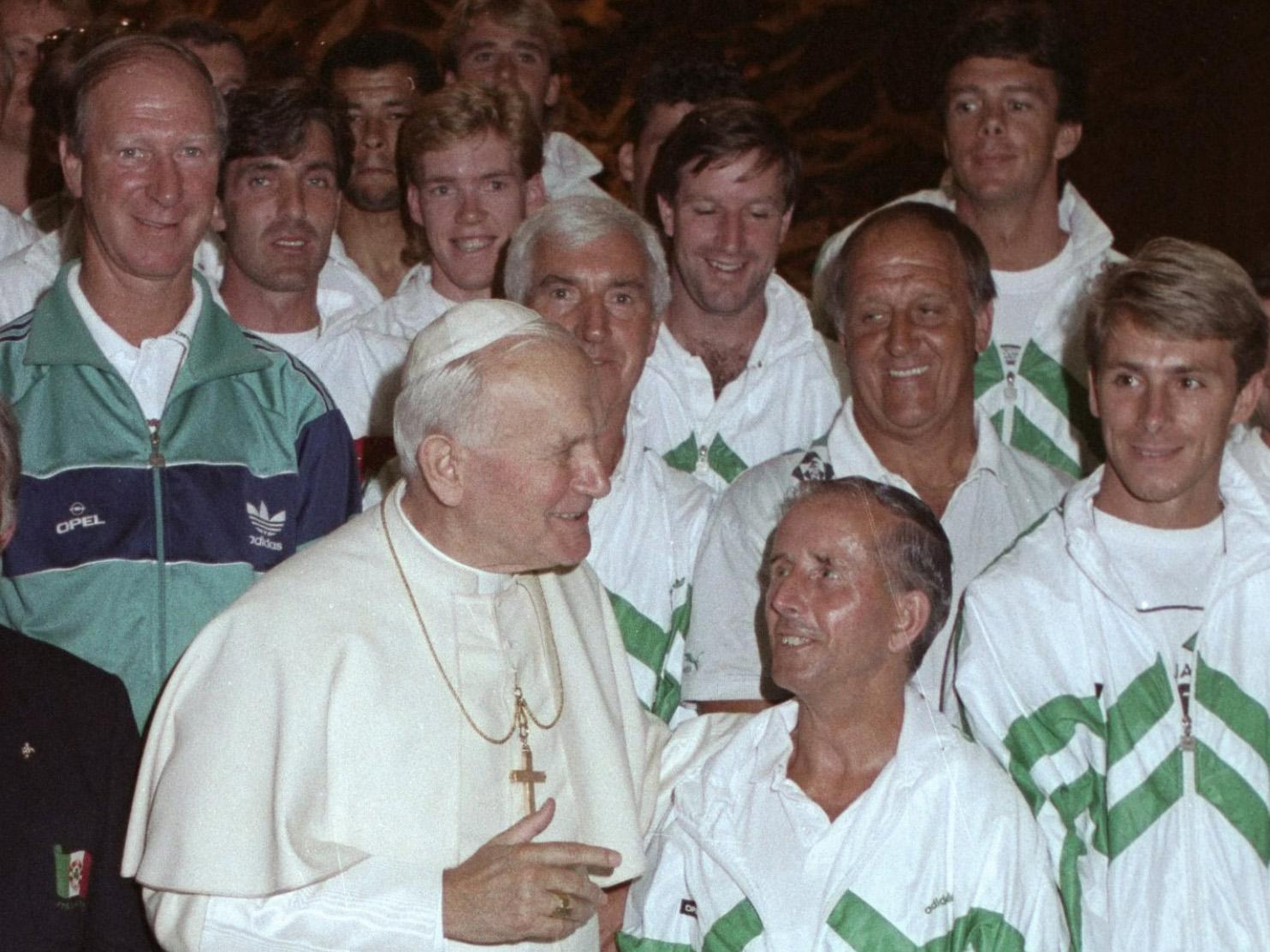

It was during this tournament that the Irish contingent was presented to the Pope, His Holiness John Paul II greeting Charlton with: “I know who you are, you’re the Boss!”

The Republic failed to reach the European Championship finals of 1992, but bounced back by qualifying for USA 94, which they commenced with a stirring 1-0 triumph over Italy, one of the strongest teams and the eventual runners-up.

In the second phase they were eliminated by Holland, but it had been a valiant campaign and one laced with controversy as a testy Charlton had conducted various spats with the organisers, notably about pitchside provision of water for his players against Mexico in the high humidity of Orlando.

Back home, having already become the first Englishman in the twentieth century to be made a Freeman of Dublin, he was lovingly dubbed Saint Jack, a tag he was to retain for life in many quarters.

However, the footballing messiah who had led the Irish from the wilderness to a best position of sixth in the Fifa world rankings was to leave his job within 18 months.

Having failed to reach the 1996 European Championships in England, he attracted inevitable criticism, particularly for what some pundits saw as over-cautious team selection, and he was not disposed to accept it with grace.

Press conferences became increasingly grumpy, even stormy affairs and in December 1995, Charlton resigned after 46 wins and only 17 defeats in 93 games.

Sadly, although he had always intended the Euro 96 campaign to be his last, he felt that he was hustled into his decision by the Football Association of Ireland, which was anxious to look to the future.

Even after that he was mooted as a possible England boss, but that was never likely to be a starter for a 61-year-old who relish the extra time he now found for his beloved fishing and shooting – not that he had ever denied himself these pleasures – and he massaged his income considerably as one of the most in-demand of after-dinner speakers. His family brought him immense pleasure and satisfaction: as well as Pat, whom he married in 1958, he is survived by their children John, Deborah and Peter, grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

Publication of his autobiography in 1996 drew attention to a rift with Sir Bobby Charlton, their relationship apparently having failed to survive a vast gulf in temperament and outlook. It was fractured almost irreparably that year when their mother, Cissie, died and Jack accused “Our Kid” of not visiting her before her death. Bobby had his say a decade later in his own autobiography, castigating his elder brother for remarks made about his wife Norma.

It took the tragic death of fellow World Cup hero Ray Wilson to finally reunite the warring brothers, who put their differences aside to attend his funeral in June 2018. It was a poignant footnote to two lives of exceptional achievement.

Clearly, though, the older brother had no regrets about any aspect of his vigorously conducted past. As he put it when reflecting on both his Irish interlude and his career as a whole: “The crack has been great.”

Jack Charlton could have no more fitting epitaph.

John Charlton, footballer and manager, born Ashington, Northumberland, 8 May 1935, died 10 July 2020