In 1974, King Crimson released one of their most underrated, at the time, albums. Red, created by the powerhouse trio Robert Fripp, John Wetton and Bill Bruford, didn’t even reach the UK Top 40 and yet it’s now regarded by many as a key work – not only in Crimson’s back catalogue but also as a foundation stone in what would later become known as progressive metal. On its 50th anniversary in 2024, Crimson’s alumni told Prog about the allure of an album that’s reduced some adults to tears.

At the completion of a take on the new instrumental track, Robert Fripp, Bill Bruford and John Wetton down tools and file out of the heavily padded door in Olympic’s Studio Two and into the adjacent control room, where engineer George Chkiantz sits at the 16-track desk. The trio are keen to listen back to their work. George asks his assistant to cue the tape and press play. The chain-mounted Tannoy speakers dangling from the ceiling deliver the music in the confines of the relatively small space with such a punch it feels like being hit by a 10-ton truck.

As the two-inch tape spools through the machine, each player’s attention zeroes in on the tiniest inflection within their respective performances, quality checking at a micro-level for any faults that might have gone unnoticed in the heat of the take. At the same time, they are also considering the macro level, pulling their respective viewpoints to also be able to take in the totality of the bigger picture, assessing the feel and weight of this new composition.

After the final note has died away Fripp asks, “Well, what do you think?”

“I’m not sure,” replies Bruford. “The tune reminds me of Tea For Two, you know? I don’t really get it.

“Well, we don’t have to use it,” offers Fripp.

“No,” says Wetton. “We use it!”

It’s interesting to think that, had the conversation in early July 1974 gone in a different direction, the track Red might not have made it to the record, instead consigned to the vaults or perhaps appearing on a future Fripp solo record.

“Bill did not get the piece Red, where he had just played the defining drum part – one of the highlights of my time working with Bill; he just didn’t get what had happened,” Fripp says with a note of incredulity in his voice. “My response to that, whether at that particular moment or shortly afterward was, ‘Well, look, if you want to use it and yet you don’t know what you’re dealing with, instead of sharing the publishing for writing it on this song, I will claim 100 per cent of the publishing.’ Which was agreed, but never happened. Eventually, sometime in 2007/8, I was in touch with Bill and with John, and we had that finally, as agreed, put in place some 40 years after recording Red.”

Nothing in King Crimson is ever quite as straightforward as it might be, especially when it comes to charting the road to Red. Along the way, the gnawing combination of bone-deep exhaustion, individuals variously in the thrall of a crisis of confidence, spiritual epiphany, substance abuse, and competing aims would snag and eventually unravel the fabric of the band to the point where it all came apart. By its release in October 1974, King Crimson had, in Fripp’s words at the time, “ceased to exist” – and despite positive reviews it failed to make it into the Top 30 album charts, peaking at No.45 for just one week, making it Crimson’s poorest-performing album of the 70s.

Yet in the face of adversity and commercial indifference, Red’s reputation and influence has steadily grown in stature over the 50 years since its recording, and it’s often regarded by many commentators – as well as the band themselves – as King Crimson’s most accomplished album since the wildfire success of their 1969 debut.

When the Islands-era band of Ian Wallace, Boz Burrell and Mel Collins sheared away from Fripp in April of 1972 following a gruelling two-month North American tour, the guitarist threw himself into producing free-jazz acts and Robert Wyatt’s second Matching Mole album, all while considering his next step. What came next was more of a giant leap with the formation of the Larks’ Tongues In Aspic quintet.

Recruiting avant-garde game-changing percussionist Jamie Muir; a young unknown violinist, David Cross; Family bassist Wetton and firebrand Yes drummer Bruford, Fripp rebuilt King Crimson from the ground up with a distinctive emphasis on a harder, precision-tooled sound informed by the ample reserves of musical technique of its eclectic membership. With such an expanded musical vocabulary, Crimson reached comfortably into free-jazz expression as well as the dynamics and asymmetric timbres more akin to contemporary classical music than rock’n’roll.

Perhaps more important than any of this, they had at their disposal a unique and magical chemistry that enabled them to pursue collective improvisation on the turn of a dime. It was in the high-stakes environment during this short-lived incarnation’s only UK tour, in the winter of 1972, that the seeds of the songs Fallen Angel and One More Red Nightmare were planted and left to slowly germinate. With Muir abruptly quitting in 1973 – just before Larks’ Tongues In Aspic’s release – the remaining quartet doubled down on the amount of improvisation within their live shows, integrating written material and spontaneous compositions to the point where audiences were mostly unable to tell them apart.

Examples of this approach can be found on 1974’s Starless And Bible Black, including the diaphanous title track, the pastoral calm of Trio, We’ll Let You Know’s querulous mutant funk, and later, Providence from Red, where the mood shifts from gothic ambiguity to confrontational avant-rock. All of these pieces, especially the last track taken from Crimson’s final tour of the 1970s, demonstrate how important being on the road was for Crimson’s creative process. But it came at a price.

These days the average UK and European touring itinerary of a moderately successful group might stretch to around seven to 10 consecutive days. Fifty years ago that would easily turn into weeks, with only a few days off in between. While Crimson were popular enough in Europe, their American album sales figures were never remotely close to that of Pink Floyd, Jethro Tull, ELP or Yes – but the feeling in much of the Crimson camp was their future lay not in Europe, but firmly across the Atlantic.

Throughout 1973 and the bulk of 1974 they schlepped between the East and West coasts and many points north and south, toiling away in incongruous support slots, slowly but surely pushing their way up to the top of the bill as they diligently worked the college circuit and the larger theatres of the day. In the popular imagination, being on tour might be a glamorous cavalcade of foreign travel, swanky hotels, sightseeing and the ego-stroking payoff of enthusiastic crowds cheering your work to the rafters. Of course, the truth is somewhat more prosaic. Touring then, as now, inevitably took place within the insular bubble of getting from A to B. Back then, hotels for King Crimson were entry-level. The possibility of appreciating the local sights was limited, as a day off would almost always be spent travelling to the next venue, given the distances involved.

Touring largely consists of a lot of waiting around in anonymous airport lounges or the back seats of saloon cars on featureless interstates with a couple of local pit stops. Faced with this unwavering diet, even the well-adjusted can be undermined by the cumulative, potentially destabilising ennui and inertia that gets under a person’s skin. Some deal with it better than others.

Bruford kept busy, reading, attempting yoga, practising saxophone with a sock stuffed down the bell in the privacy of his hotel room. Fripp, who’d also been constantly on the road since 1971, not only systematically practised guitar as much as he could, but also read voraciously and kept a journal. Just as Jamie Muir had quit Crimson in 1973 to pursue a spiritual calling to become a Buddhist monk, during that final American tour Fripp’s encounter with the writings of English mystic JG Bennett deeply and profoundly resonated with him, confirming his sense of needing to alter the course of his life.

Like so many of his contemporaries in rock, Wetton, as a young, single man, eagerly embraced the ‘sex, drugs, rock’n’roll’ lifestyle. In the short term, hedonism was good fun, even though it would sometimes affect his judgement during the recording of Red as he experimented with different substances. In the longer term it became the foundation to Wetton’s well-publicised battle with addiction in later life.

I loved being onstage with that band… The bits I didn’t like were when I let myself down, when I lost heart, when I lost courage

David Cross

For David Cross, life in Crimson was rewarding from a musical viewpoint, although not without its challenges, given his proximity to Wetton’s increasingly louder-by-the-gig bass cabinet and suboptimal onstage monitoring. He felt he was becoming marginalised by the combined force of Wetton and Bruford’s sound, described by Fripp as being akin to a “flying brick wall.” Well before the end of the tour, Cross had decided to quit – unaware of the decision taken by the band to fire him when they returned to the UK.

In between dates performing the Larks’ Tongues In Aspic album in full with his live band Cross, he candidly admits that his last few weeks were extremely difficult. “I loved being onstage with that band, especially when we were improvising and when we were in the zone on stuff, able to really push forward. That was lovely. The bits I didn’t like were when I let myself down, when I lost heart, when I lost courage; I didn’t like that. I suffered from a lot of anxiety, which was probably caused by me drinking a lot.

“I started developing height phobia and stuff like that by that stage. That happened in a hotel in Texas. It was one of those first hotels that was built with the balconies looking down inside and I was put up on the 30th floor or something. I just suddenly didn’t like the drop down there as I tried to get to my room, so I got moved down to about the 11th floor. The whole process of my mental health deteriorating like that was in itself frightening anyway. You do feel it’s just happening to you.”

With Cross full of self-doubt and his problems beginning to affect his performances, Wetton in particular argued that what the group needed to boost their chances of really breaking America in 1975 was a stronger instrumentalist. Violinist Wilf Gibson, who had been in the Electric Light Orchestra, was sounded out by EG Management about joining; but he had a young family and did not want to tour. Wetton’s real preference was for Crimson co-founder Ian McDonald to rejoin, leading to the sax player and multi-instrumentalist being invited to guest on One More Red Nightmare and Starless.

In their soundchecks at the time, Fripp would often throw out a chord or a motif which might or might not get picked up on by the others. One of these had been the see-saw riff of Red. Sometimes, however, a more fully fleshed-out idea would be presented in the more formal surroundings of the rehearsal room. Just as the inclusion of the title track had momentarily hung in the balance at Olympic Studios, Starless – one of the most well-regarded and most recognised King Crimson tracks – almost never happened. Wetton and lyricist Richard Palmer-James penned a ballad and presented an early draft at a KC rehearsal in late 1973. Wetton once recalled being crestfallen when his sensitive song was met with polite indifference as the band quickly went on to other things. “Rehearsals were always an icy and rather bleak kind of engagement,” comments Bruford. “There was a lot of floor staring.”

However, what Wetton’s bandmates did like was the line from the song’s chorus, ‘starless and bible black.’ Co-opted by Palmer-James from the opening passage of Dylan Thomas’s 1954 radio play Under Milk Wood, it connected so strongly with Wetton and the other Crims that it was assigned to an instrumental improvisation and used as the title to Larks’ Tongues In Aspic’s follow-up album. However, before its release, by the next bout of writing and rehearsing in February 1974, the quartet revisited Wetton’s ballad. This time it would be augmented by several decisive and transformational new elements. The first came while the band were touring during the tail-end of 1973.

A piano is wonderful… you get a rhythm with a bit of melody, then you give it to John Wetton or Robert Fripp to see what they do with it

Bill Bruford

“I can remember standing onstage in a soundcheck messing around with it, and just trying to trying to find some kind of satisfaction with it,” Cross says of the mournful, woebegone melody, which opens Starless. “I was experimenting with this kind of leap. I was always trying to find a way to get up and come down again. And I wanted to get up the octave and I wanted to feature the ninth of the scale, which is very powerful. I wanted to do it in a satisfying way. So I was always playing around with it, just wearing everybody down around it until we took some notice of it. Robert probably just got bored with listening to me fluffing around with it, and he picked it up and did some stuff with it and probably turned it into a proper tune, or I’d have just kept flapping around with it. He reckoned I started it and he finished it.”

Another feature of the new piece came after Bruford was playing piano at home. “I was interested in music in its totality,” explains Bruford, six decades after he came up with the glowering bass melody that underpins the central section. “A piano is wonderful because you can see the notes and it’s highly rhythmic. So for someone like me, who’s going to do a rhythmic thing, just bang on a note, and out comes a rhythm on a pitch. If you then change some of those notes you get a rhythm with a bit of melody, and then you give it to John Wetton or Robert Fripp to see what they do with it.”

What Fripp ended up doing was to distil all his years of experience, skill and dexterity into one note played across two strings with some pitch bending for over four minutes, something that Steven Wilson would come to describe as “The death of prog solo.” Adding to this already exciting brew was a bass riff that had originally been part of the early versions of Fripp’s Fracture, written and performed during 1973. That fast-moving jazz-rock-style figure, propelled by the bass, provided the platform for the blowing/soloing section before the majestic recapitulation of the main theme brought the whole piece to a thunderous completion.

Receiving its first live airing just days after the arrangements for all these separate instrumental sections had been hastily completed, Starless was a huge hit with the crowds – thanks in part to the simple but incredibly effective lighting cue that suffused the entire stage in an infernal, glowering crimson/red light as the piece relentlessly grew in power and magnitude over that memorable Bruford bass line. As Fripp noted in his diary after the band’s last performance in New York’s Central Park on July 1, 1974: “Lights at the end of Starless really blew the crowd. Rapturous reception... Everyone was pleased with the gig. Conversation with John Wetton – lighting effects like that really make the difference.”

By the time they came to record Starless at Olympic Studios in July 1974, the remaining trio had played the song in concert more than 51 times. The fact that Crimson had at last been able to channel the raw energy of their live performances into the studio environment makes the finality of Red all the more poignant. That it was and remains such a powerful statement is all the more amazing considering what was going on under the psyche of the group.

As the sessions got underway, when Fripp told his colleagues that he was “withdrawing the passing of his opinion,” and that his thoughts didn’t matter any more, Bruford and Wetton decided he was simply “pulling a moody,” and got on with the task in hand. Fripp’s approach was part of what he would later describe as a strategy of radical neutrality, “the doing nothing that enables doing everything.” His avoidance of taking the initiative in the way he had done in previous recordings came in part as a response to reading JG Bennett’s work; and, during the weeks and months out on the road, a growing realisation that the madness and excesses of the music industry of which he’d been a part for five years were inimical with the life he wished to lead. The burden and responsibility of steering King Crimson against the crosswinds of commerciality and artistic compromise was ultimately becoming too much for him.

For me, the most satisfying of Bill’s drumming at any time in King Crimson was on the Red sessions

Robert Fripp

His idea of taking a sabbatical and there being a Frippless Crimson, with Ian McDonald rejoining the group on a permanent basis, was discussed; but ultimately nixed by EG Management, then already lining up another push in North America after Red’s release. Exhausted at the prospect of another year on the treadmill, Fripp increasingly saw the only way out was to put an end to the band. Very little of what was going on both on the inside and outside of Fripp’s world was discussed with Bruford or Wetton. “I think it was probably very hard for them,” Fripp reflects today. Looking back on the making of Red, Bruford agrees with his ex-bandmate’s assessment.

“It was extremely hard to deal with. But I also understand that if you impose these incredibly hard obstacles and hurdles to making something, and people stay in the room, you might just get there. John and I stood our ground and said, ‘All right.’ Well, we said, ‘Sod that – we’ll do whatever we can here to make something up out of this.’ I think John and I were emotionally very, very involved. Finally, towards the end, it got down to the mixing and it was very much John and George Chkiantz who took the baby from the bathwater, wrapped it up and towelled it down. Giving birth to the thing was rough work. I’m glad Robert acknowledges that at least his radical neutrality was quite a creative stimulant.”

The power of the studio recording, with guests from the band’s past including McDonald, oboist Robin Miller, cornet player Mark Charig and Mel Collins, plus subtle orchestral additions such as the cello on Red itself and the four double basses lending the coda extra dramatic heft, is palpable. Even the chance discovery by Bruford of a 20-inch Zilket cymbal, upturned at one side like an Australian bush hat and discarded in a bin at Olympic Studios, inadvertently became one of the defining sounds of the album.

Even now, Fripp is in awe at what they managed to record. “I was simply going with whatever was coming my way. And what was coming my way from John and Bill was startlingly impressive. When we actually played Red, the track, I remember Bill’s playing...” He pauses, momentarily lost in admiration. “It still defines the part with the wonderful cracked cymbal. I mean, fabulous stuff... Bill was at the height of his young powers, and for me, the most satisfying of Bill’s drumming at any time in King Crimson was on the Red sessions.”

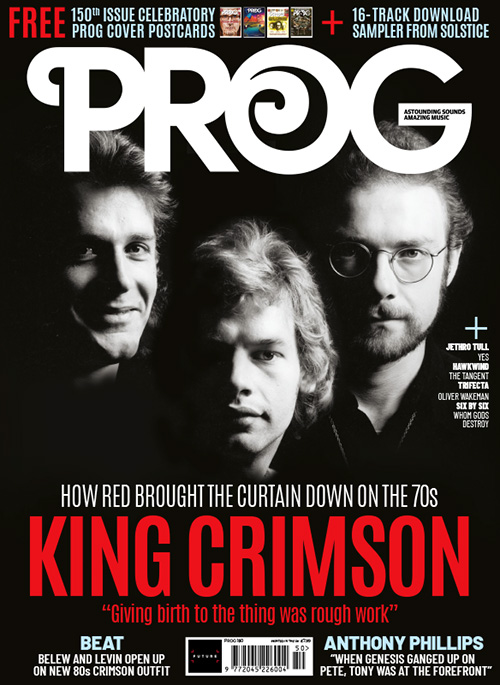

If the aim of all that touring had been aimed at building momentum and visibility, it’s no accident that Red was the first Crimson album to feature the band themselves on its front cover – something that EG Management and Wetton had pushed for. Coupled with the individual shots taken by Gered Mankowitz (who in a spooky coincidence had taken the publicity shots for Giles, Giles And Fripp six years earlier), Wetton came up with the idea to have the back cover photo of a VU meter crashing into the red-etched No.7, symbolising that this was the album that was going to push Crimson into the next level. “I totally loved that cover,” says Bruford. “It suited the particular feel of the album: these three fairly stern faces, obviously in some kind of relationship; the good, the bad, and the ugly, appearing so starkly on the front. It suited the entire vibe so very well.”

It’s such a little album in many ways, but it seems to have leapt out of its box of progressive rock and become greater than that

Bill Bruford

Fripp hated it in 1974, but in keeping with his policy of radical neutrality, kept his misgivings to himself. These days, he’s more forthcoming describing it as, “fucking appalling. Why was it fucking appalling? Because one of the powers of King Crimson’s artwork was the anonymity of the players. What’s important is the music, King Crimson, not the members of the band.”

When asked to choose his favourite of the three studio albums released in the 1970s, Wetton chose Red without any hesitation. It’s the same for Bruford, who has been lecturing to university students since gaining his doctorate in 2016, and notes that he has seen the appeal of the record – along with some of the others he was involved with half a century ago – finding favour with a younger audience.

“Quite why it has longevity, and these little albums somehow seem to become greater than they’re supposed to be, is odd and something to do with cultural change, I think,” the drummer says. “Young people seem to appreciate the old stuff, parroting their parental opinion that the new stuff is over-processed, over-regulated and corporate. Red seems to point in the direction in which music might be other than that, or continue to be other than that. In modern terms, it’s fairly unprepossessing stuff. I mean, the album has five tracks, of which there are only three songs on it, the other two being instrumental. It’s such a little album in many ways, but it seems to have leapt out of its box of progressive rock and become greater than that.”

After Crimson split in 1974, it was seven years before the title track got its first live outing as a surprise inclusion on the setlist of the 1980s incarnation. That, though, is nothing compared to the 40 years that elapsed before Starless was played again, from 2014 onwards. This latter period of the band’s life also saw Fallen Angel and One More Red Nightmare – both numbers for which Fripp harboured a particular affection – finally make their live debut.

“All of the written pieces on Red were stunning,” he says. “The Discipline quartet played Red, but not properly, in my view. We did a good version of it but didn’t have the weight that the seven- and eight-piece had to bring to those pieces. Red was an instrumental, so you didn’t need a vocalist. Jakko Jakszyk could deliver authentic versions of all that early material. Astonishingly good versions.”

I’ve said before, and I’ll say it again – the musician doesn’t write the music; music writes the musician

Robert Fripp

During that period when Starless was performed, it was common to see some audience members moved to tears. “There were times playing it live where I was in tears,” agrees Fripp. One admittedly crude measure of the way the song has continued to grow and resonate with new audiences and generations alike are the 14 million hits of the 2015 live performance notched up on YouTube, easily outstripping 21st Century Schizoid Man as King Crimson’s most popular number.

Fripp is at a loss to explain the track’s mass popularity. “I can’t speak for the multitude who pile onto YouTube, but I’ve said before, and I’ll say it again – the musician doesn’t write the music; music writes the musician. And if you’re fortunate and manage to get yourself out of the way, sometimes music like that can happen.”