Metallica get the same 365 days as the rest of us, but something happens to them on a trip around the sun that spins time all out of proportion. More happens than seems possible.

When lead guitarist Kirk Hammett speaks to Total Guitar during a rare moment of respite from the band’s remorseless trek across the States, pillaging its largest stadia, he barely pauses for breath as he reels off the highlights from his year.

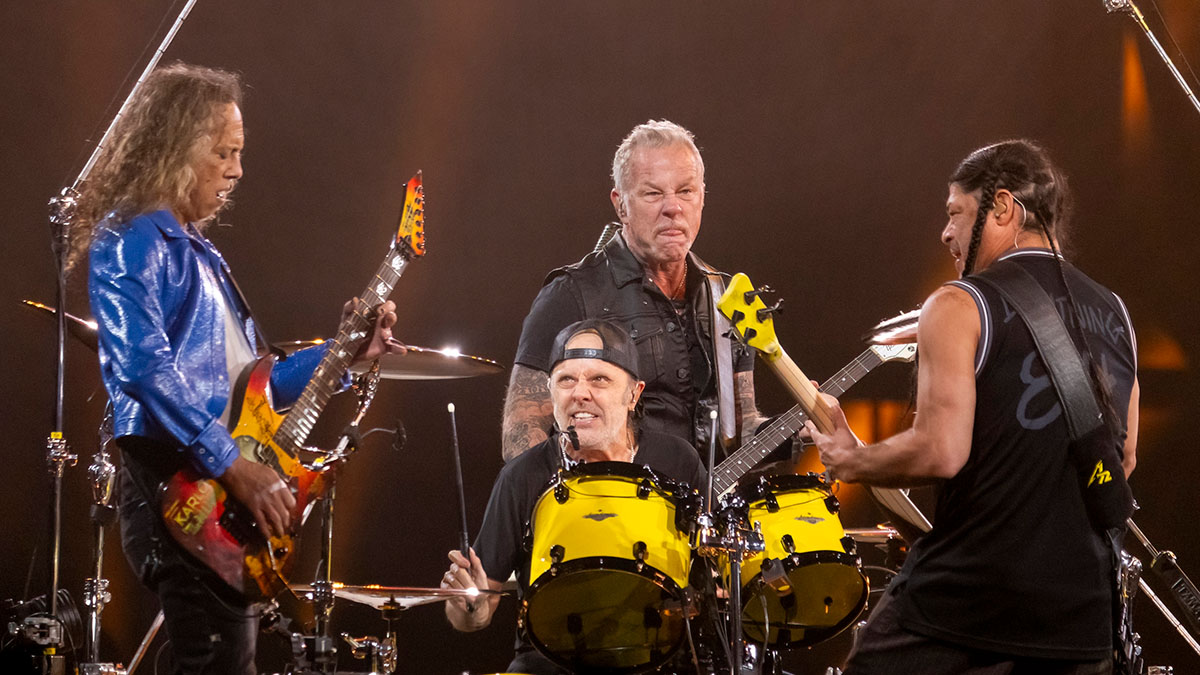

First, the M72 World Tour; two nights in a stadium, no two the same, with no-repeat setlists culled from the most formidable back catalogue in metal. The scale of these shows is on a different level to anything Metallica have attempted before, and the sheer size of the stage has meant that Kirk has had to find a new way of locking in with drummer Lars Ulrich.

“We really had to change our whole approach to playing live because that stage is so goddamn big I am literally 100 feet away from Lars,” Kirk says. “His hi-hat in the count? Sometimes I can’t hear that hi-hat but I can see it, and that is what I have to rely on, and that’s the case with all of us.”

The tour has included festival stop-offs, such as Download and Power Trip – that big shindig in the Californian desert with Iron Maiden, Guns N’ Roses, Tool, AC/DC and Judas Priest.

Kirk has also enjoyed some extra-curricular live engagements: jamming onstage with Journey and trading licks with that band’s founder Neal Schon on their ’70s classic Wheel In The Sky and Metallica’s anthem Enter Sandman; performing with Eric Clapton, Ronnie Wood and more at the Royal Albert Hall to pay tribute to Jeff Beck.

Then there are the guitars of 2023, with Gibson rolling out various replica editions of Greeny, the 1959 Les Paul Standard famously owned by the late Peter Green, latterly the late Gary Moore, and Hammett since 2014.

Kirk’s 1979 Flying V that consecrated Metallica’s thrash sound on the band’s first three albums has enjoyed similar treatment.

ESP has done its bit, too, refreshing Hammett’s signature range with the offset LTD KH-V, offering frontman/rhythm guitarist James Hetfield’s Vulture in Olympic White.

Kirk’s personal arsenal has grown. With the help of Joe Bonamassa – a man with a bloodhound’s nose for aged nitrocellulose – Kirk finally got his hands on the ‘Factory Black’ 1959 Les Paul Standard that had eluded him for over a decade, costing him considerable blood and treasure along the way.

“It is so beautiful. I love it,” he says. “I tried to get it once and got ripped off. I tried to work out a deal where I was going to trade 30 guitars for that guitar but ended up getting 30 guitars stolen! I kept my eye on it for a long time. About a year-and-a-half ago, Joe Bonamassa texted me and said, ‘I know you love that black Les Paul. It’s at Carter Vintage right now. Call them ASAP!’

“I called them up that morning and then my second call was to Joe. ‘Joe, thank you so much for alerting me, and, and on top of that, not buying it!’ I’m probably going to be using it in the studio right alongside Greeny as Greeny’s foil. I call it Ella. Ella is going to be the yin to Greeny’s yang.”

But when all is said and done, when the PA powers down at Ford Field in Detroit, Michigan, sending 78,000 sweaty fans into November’s cold night air, placing this pop-cultural juggernaut into park for the year, Metallica’s story of 2023 will be about 72 Seasons. Not for the first time, metal’s own Fab Four had stared into the abyss to be reborn anew, emerging with the guitar album of the year…

If 72 Seasons is by most people’s estimation Metallica’s strongest album of the 21st century then we have the existential funk of 2020 to thank. Thursday Zoom calls under the spectre of cataclysm helped Metallica decide what sort of band they wanted to be.

There would be more trust in one another. There would be riffs. This was an era of stockpiling. In Metallica’s world, it was riffs. “We were all telling each other, ‘You gotta invest, you gotta put a riff into the riff bank!’” Those investments paid off; the riffs gave them something to build on and the rest just flowed.

“We didn’t work on it that much!” continues Hammett. “When we were coming up with the songs, we had all of them in a short space of time. Another thing that was key: because we were all in different geographical spots, the debates and the arguing was brought down to a minimum! It felt good. It was primal. It didn’t feel like there was a lot of second-guessing. Second-guessing amongst band members can lead to arguing.”

You should see it when we are in the rehearsal room working on a part. Man, the riffs fly

The songs soon took shape, some drawing from familiar reference points. Lux Æterna is as NWOBHM as Metallica get. With a less box-office production, it wouldn’t be out of place on The $5.98 E.P. – Garage Days Re-Revisited. Vocally, Hetfield operates right on the frontier of his leonine Metallica persona, redoubtable yet vulnerable. Rhythm-wise, he’s totally on brand; If Darkness Had A Son and Sleepwalk My Life Away are as good as dental records or a fingerprint.

“You should see it when we are in the rehearsal room working on a part. Man, the riffs fly,” Kirk says. “The riffs fly, bro, between James, Rob [Trujillo, bassist] and myself. The whole process is a lot of experimentation, looking for different note patterns, different techniques, different ways to pick the notes, ways to phrase. We are always searching for it.”

Metallica hired producer/engineer Greg Fidelman (Slipknot/RHCP) to play midwife to this creative outpouring. Hetfield and Hammett needed tones. As Fidelman told TG, Hammett would use his signature Randall head, Friedman heads with the fire-breathing HBE channel, a Mesa/Boogie Dual Rectifier combined with a 100-watt master volume Marshall JMP.

Hetfield mixed and matched from his trusty Mesa/Boogie Mark IIC++ – aka, the ‘Crunch Berries’ Master Of Puppets amp – a Marshall Super Lead modded by the legendary José Arredondo, and 100-watt heads from Diezel and Canadian boutique amp brand Wizard.

There were lots of amps, lots of volume, air getting pushed out of the speakers, but not too much gain. This isn’t 1989. Now, the watch word is clarity, and if you’re looking for the secret sauce you’ll find it in the circuit of the SoloDallas Schaffer Replica EX Tower.

“Right on, bro, it’s all about the Tower,” Kirk says. “The first version of the Tower that came out about five or six years ago is built so horribly. It’s flimsy plastic but it’s the best-sounding thing. They have the foot pedals out and the foot pedals are great but for some reason this fucking thing sounds 10 per cent better!”

That Hammett deployed the secret weapon behind the searing tube-heat warmth of Angus Young’s Back In Black tone betrays his thinking. He wanted his leads to have more rhythm, to be conceptually smaller, less about modality and structure, more guided by instinct, just how they did it in the ’70s. Just how Angus Young did it.

“I love Angus’ groove, and over the last couple of years or so I have found a bigger appreciation of his playing because Angus always plays for the song,” Kirk says. “Some of his solos are crazy and wacky and out there but they always, always are in that context of the song, and it never sounded like Angus worked anything out.”

I love Angus’ groove, and over the last couple of years or so I have found a bigger appreciation of his playing because Angus always plays for the song

Hammett didn’t either. He knew the key. Hetfield’s lyrics and vocal set the tone. Whatever happened was all in the moment. He tracked dozens of solos before turning them over to Fidelman and Ulrich.

“It was a huge risk-taking, a huge experiment, and to this day I’m wondering if I pulled it off or not,” Hammett says. “But I had to do it this way because it was how I felt inside. I wanted spontaneity. I didn’t want picture-perfect solos because some of my favourite players’ solos were kind of rag-tag and I love that.

“My solos are a reaction – absolutely 100 per cent – to what’s happening in the song because it was my only point of reference. I purposely didn’t work out anything so that all I had to fall back on was what everyone else can fall back on, which is pure feeling, and that in itself is a challenge.”

You can call 72 Seasons metal, thrash, whatever, but there is a ton of musical information to process before reaching any conclusion. Some songs reference vintage British steel, others are clad in the downcast timbre of Iommi; album closer Inamorata is the sound of Metallica processing Black Sabbath’s influence through the same longform sensibility that brought Orion into this world, complete with a harmony solo Hetfield composed on the spot.

You Must Burn! traffics in a vibe that could be the summer of 1991 re-revisited. Lars Ulrich’s snare sounds like the discharging of a firearm. There’s even a call back to Neal Hefti’s Adam West Batman theme in Shadows Follow. What are Metallica if not a rock ’n’ roll band?

James will play something when he is frigging trying to tune his guitar and Lars starts screaming, ‘Stop! What did you just play!?’ ...It’s all about experimentation

“Thank you for recognising that, because we are,” Kirk says. “That’s really funny because we called that riff ‘The Batman Riff’, and I know exactly what you are talking about.

“One thing I noticed from watching AC/DC at Power Trip is that AC/DC are actually a bunch of different bands. AC/DC is a fucking boogie-woogie blues bar band… a rock band… a hard-rock band… a heavy metal band. They are all those types of bands rolled into one. It goes from ‘Baby, please don’t go’ to fuckin’ Back In Black.”

This could be Metallica, too; a sound and identity so big it spreads itself across categories. The depth of Metallica’s songwriting vocabulary owes much to Ulrich’s restless deportment and uncanny ear. There are few, if any, with a better sense for a song’s raw material.

“Sometimes, I’ll just sit there out of frustration because I can’t come up with a heavy riff, and I’ll start arpeggiating E minor and then muting it, and then Lars will go, ‘Hey! What’s that!?’’ Hammett says.

“And it’s so far away from what I am trying to do, what anyone is trying to do! Or James will play something when he is frigging trying to tune his guitar and Lars starts screaming, ‘Stop! What did you just play!?’ James will start up, ‘I’m just tuning my guitar!’ ‘No, that other thing.’ And James will start teasing Lars. It’s all about experimentation.”

Even if Angus Young was magnetic north as far as inspiration went, and improvisation was the radical modifier guiding his note choices, there is no mistaking the lead guitar on 72 Seasons as anything other than a Hammett solo. They sit high in the mix, like they’re in the room with you.

John McLaughlin is my kind of guy. He is spiritual. He meditates. He does yoga. He’s a vegetarian. Boom!

The squawk of wah still vocalises his phrases but Hammett is a very different player these days. Greeny has a lot to do with it. 72 Seasons was a two-hander between the storied single-cut and Hammett’s ESP Mummy, his best-sounding Strat-style guitar. It is Greeny that leads Hammett down these new paths, as though it has a muscle memory of its own, an intention pressed upon it by its former custodians.

“I play Greeny differently to all the other guitars, and I play Greeny the most out of all my guitars,” Kirk says. “I don’t know what it is but when I play Greeny my approach is different. I want to hear Greeny sing. I want to hear the wood. I love hitting powerchords on Greeny.”

Ella didn’t quite make the cut but shows great potential. “It doesn’t quite have that extra 10 to 15 per cent aggression,” he says. “Greg and I came to the conclusion that it is almost too pretty, but for single lines, single note stuff and leads, oh man, it’s so nice. It sings. It is so well balanced. It is a real blues, jazz, rock guitar.”

Greeny’s history inspired a deep dive into British blues and rock players from the ’60s onwards, another factor colouring Hammett’s lead guitar. Right now John McLaughlin is the one.

“I’ve been on a John McLaughlin tip for the last year or so because his playing is so out there and diverse, and unique,” Kirk says. “I love it. And, as a person, John McLaughlin is my kind of guy. He is spiritual. He meditates. He does yoga. He’s a vegetarian. Boom!”

The biggest change in Kirk Hammett is that he’s left writer’s block behind. He even has a whole methodology that he promises will help pros and six-string noviciates alike.

He sits down, clears his mind as best he can. He relaxes. Then he plays. Where he is on the fretboard is immaterial. The crucial component is the listening.

“I just listen to the notes and I start getting ideas,” he says. “All of a sudden I have clay to play with. I’ll just play with that little thing for 10 or 15 minutes and if it shapes itself into something then that’s great, if it doesn’t I’ll just move on. It’s a real slow, quiet, very observant sort of awareness.”

You’ve got to be aware if you want to be a musician. There’s music all around us. At home in Hawaii, Hammett has the pulse of the ocean keeping time. He has got the birds in the trees, air traffic…

“I love playing my guitar outside because I love hearing the sounds of nature,” he says. “I love incidental sounds. A plane will be flying over me and I’ll find the pitch. It’s weird. Daimler-Benz, who makes all these airplanes, I think they fucking pitch all the airplane motors because they almost always start in A then modulate down to F#. It’s so crazy, [if] a plane [is] flying over me, I’ll find the tone.

“Sometimes I’ll hear this weird bird do a mating call and I’ll try to mimic it on the guitar. There’s stuff that’s all around you, giving you little nudges towards ideas. You can get ideas anywhere if you just open up your ears and let your creativity flow.”

Metallica are in the memory making business. That’s what spectacles such as the M72 World Tour are for. Such endeavours aren’t without risk. Hammett and Hetfield take precautions, deploying Fractal Axe-Fx units in live rigs for low-noise consistency. They have two monitor engineers between four.

It’s crazy because when I am facing out into the stadium it feels like a stadium show, and when I turn around and see the Snakepit, it feels like we are playing a nightclub!

But for all Metallica’s struggles over the years, fear of failure has never constricted them. Hammett says it is freeing being up onstage, totally exposed and on camera. What else is there to do but to perform and engage the crowd?

“It’s pretty wacky on the technical side but once you go out there and things are sounding good, my guitar is sounding good, I can hear myself, man, there’s something about that stage,” Hammett says.

“There’s nowhere where we can hide. We are exposed all the time, so we make the most of it and we’re just like, ‘Hello, everyone! Here we are!’ And it’s crazy because when I am facing out into the stadium it feels like a stadium show, and when I turn around and face into the inner part of the stage and see the Snakepit, it feels like we are playing a nightclub!”

The triumph of the M72 World Tour is that it has all the spectacle that a stadium show implies and yet it feels as though it could be ’83 and you’re down the front at The Metro in Chicago. This intimacy makes such memories indelible.

Even Hammett flubbing the intro to Nothing Else Matters and restarting the song creates a special moment for audience. Band and crowd alike, we are all human.

I don’t take myself that seriously. I’m not going to go up there and say I’m some f**king perfect machine

“What you definitely are doing is setting yourself up for a lot of comments afterwards!” Kirk says. “But I didn’t care, man. In that moment, I was like, ‘Fuck! Y’know I’m going to play that for you decently because you guys deserve to hear it correctly!’ Yeah, I fucked it up. So what!? I don’t take myself that seriously. I’m not going to go up there and say I’m some fucking perfect machine.”

It did momentarily freak him out, shaking his hands post-show to see what was up. “Then I thought, ‘Fuck! I’m dehydrated,” he says. “That’s why. I’m not as limber as I usually am. Playing in dry heat, in the middle of the desert, I just didn’t drink enough water.”

Hammett has another one if you want to follow Metallica into the memory-making business. All that time you spend on solos? It’s all for nothing if you don’t have a song.

“I hate to say it for all your readers out there, but non-musicians, who are the majority of the fucking listening world, they are not going to remember guitar solos,” he says. “But yeah, they are gonna helluva remember a great melody, and they’re really gonna remember a great song – especially a song that’s gonna bring them to a different place from where they were five minutes previously.”

I hate to say it for all your readers out there, but non-musicians, who are the majority of the f*cking listening world, they are not going to remember guitar solos

His advice? Start writing songs. It doesn’t matter how bad you suck. This is where it all starts. Trust him. Kirk Hammett has been there.

“I figured it out when I was 15 years old,” he says, recalling a conversation he had with his childhood friend John Marshall, who ended up being Kirk’s tech for many years, as well as playing guitar for Metallica as an emergency stand-in for James Hetfield during two tours – first in 1986, after Hetfield broke his wrist, and again in 1992, when James was suffering from burns following an onstage pyro accident.

As Kirk remembers it: “John Marshall and myself had literally been playing guitar for six months when I said to him, ‘We need to start writing tunes. Look at KISS, they write all their own songs… and Aerosmith, Van Halen.’ So John and I started writing music. And it was a lot of crap, but it was something!”

- 72 Seasons is out now via Rhino/Blackened Recordings.