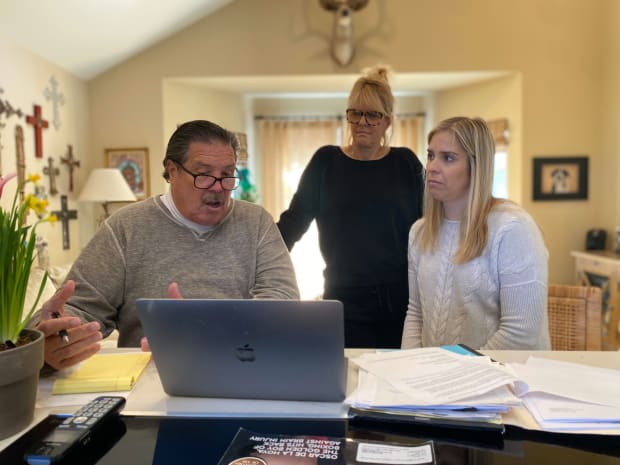

Terry and Betsy Brennan gather around a laptop in the kitchen of their home in Irvine, Calif., alongside their daughter, Chanel Brennan Brewster, as they log in to a Zoom meeting. They’re about to find out whether their son and Chanel’s older brother, former Hawai‘i football superstar quarterback Colt Brennan, died with chronic traumatic encephalopathy, the degenerative brain disease brought on by blows to the head.

Chanel, who is a few months pregnant with her second daughter, says she’s naming her after Colt—Marley James. Bob Marley was Colt’s favorite artist, and James was Colt’s middle name. A framed jersey hangs on the wall beside them, commemorating Hawai‘i’s retirement of Colt’s No. 15.

Brandon Sneed

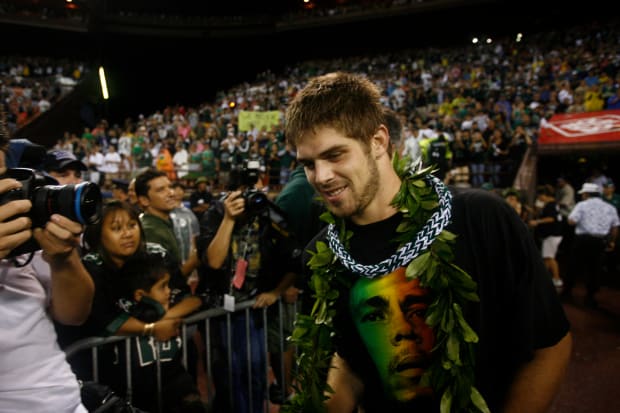

Colt had been one of the best quarterbacks college football had ever seen. During his junior year at Hawai‘i, he set the NCAA single-season record for passing touchdowns with 58 and was projected to be an early pick in the NFL draft. He chose instead to return for his senior year in 2007, when he led the Rainbow Warriors to their first undefeated season and finished second in Heisman voting as Hawai‘i’s first finalist for the award. He finished his collegiate career with 31 NCAA passing records.

Injuries and surgeries derailed his NFL career, however, and a car accident on a Kona highway in 2010 left him with severe and permanent injuries that led to the end of his football career. He struggled with alcoholism and addiction for a decade after that, in and out of countless therapy and treatment programs, before finding Tree House Recovery in Costa Mesa, Calif., at the start of 2021. He thrived as the Tree House program integrated teachings on neuroscience and biology with writing alongside intense physical training and challenges. The Brennan family felt like they had the Colt they knew and loved back.

But in May 2021, Terry and Betsy returned home from a trip to Mexico and found Colt drunk and high in their home, having suffered a relapse. He was surrounded by bottles of vodka, cans of beer and canisters of nitrous oxide, one of his primary drugs of choice. Terry drove him to Hoag Hospital in Newport Beach, where he was told they were keeping Colt in the emergency room until he was able to enter detox. Instead, Hoag released Colt around 1 a.m. that night, whereupon Colt made his way to a nearby motel. He apparently met some men who delivered various drugs to him.

At around 4 a.m., responding to a 911 call, paramedics found Colt unconscious and not breathing from an apparent drug overdose. Colt was taken back to the hospital, where he was in a coma and sustained by a ventilator and IV. When it became clear the damage done to his body and brain was irreversible, Colt was allowed to die. He was 37 years old.

Autopsy results eventually revealed Colt had died from the “combined toxic effects” of ethanol, methamphetamines, amphetamines and fentanyl. But the Brennans wanted to know more—they wanted to look deeper than the addiction, to what could have been happening in Colt’s brain to drive him into addiction, and what could be making it so hard for him to get and stay sober. The Brennans donated his brain to Boston University’s CTE Center to determine whether he had been suffering from the disease, which can only be diagnosed postmortem.

So now, on the other end of Thursday's Zoom call, Lisa McHale, director of legacy family relations at the Concussion Legacy Foundation, and Dr. Ann McKee, a professor of neurology and pathology at Boston and the CTE Center director, are ready to share what they found.

McKee said it was harder than usual for them to examine the brain due to the nature of Colt’s death. Since the drug overdose rendered Colt unconscious and unable to breathe for long enough that his entire brain looked as though it had suffered a gigantic stroke, he lost a lot of tissue that interfered somewhat with McKee’s examination.

Joe Nicholson/USA Today Sports

She also identified significant traumatic brain injuries in multiple parts of his brain. The first she noted was a massive gap in the membrane that connects the two sides of the brain to each other. Colt suffered a significant cavum septum pellucidum that ran the length of the membrane, meaning there was a gap—or a cave—all along it that should not have been there. He also suffered a loss of tissue in his right frontal lobe that essentially left a hole there due to a substantial loss of tissue caused by the 2010 car accident.

While all of these factors made it more difficult for McKee to assess the extent of CTE in the brain, McKee was still able to confirm Colt’s brain showed CTE in the frontal cortex, the brain stem and other subcortical regions. “It was enough to call CTE Stage I,” she says. “But it might’ve been greater had we been able to really assess other regions.”

The traumatic brain injury (TBI) caused by the car accident alone would have been enough to create issues for Colt, and the Brennans did see a marked change in his personality after the incident. He became more emotional, and began drinking and using drugs more. Addiction by nature hijacks brains and damages them in a way that convinces the brain it needs the addictive substance to survive. This alone is often an enormous challenge to overcome.

Add in a TBI, particularly one to the frontal lobe, and that challenge becomes magnified. CTE on top of that creates a compounding effect. The prefrontal cortex governs executive function and decision-making, as well as the ability to process emotions in a healthy manner—and shut down his more destructive impulses.

“His ability to avoid those things was really diminished,” McKee says. “He’s got impulses that he can’t control. He’s got urges that are physical in nature. There’s a physical aspect to this. It’s not just will. And fortitude. And discipline. He’s got injuries that he’s trying to overcome.”

Justin McMillen, founder and director for Tree House Recovery, says, “With that damage there, it just made it that much harder for him to become sober and sustain that sobriety, which is just heartbreaking.”

“He was really working uphill,” says Ryan Bain, a Tree House counselor and former Division I college football player. “He had a pretty limited toolkit given everything he had been through with the car accident, the damage to his brain and addiction in and of itself, without all of the other medical issues. Not to mention his fall from grace. It’s really difficult for people, the self-esteem collapse that comes from that.”

McMillen and Bain found it remarkable Colt was able to get himself healthy and sober considering all he was facing, especially in light of the CTE diagnosis. In a journal, Colt wrote about how powerless he often felt to stop himself from acting on the impulses that drove him back to drinking and drugs time and again.

“Anyone struggling with that, they’re going to have a problem with all of those things,” Bain says. “Consequence evaluation. Being able to work through intense or aggressive tendencies that are exacerbated. Planning. Rational decision-making. All of that. It just becomes more difficult, more complex.”

Treating these issues is a tremendous challenge, as well. “We really need better ways to help these guys,” McKee says. “Better ways to identify they’re going through these issues. We know this very well—that there’s almost nothing to really offer these guys. There’s very few people that even recognize this is an issue.”

Courtesy of the Brennan family

Even if it is recognized, “It is very difficult to treat.”

McKee says one way to help people suffering from traumatic brain injuries and symptoms of CTE is to understand exactly that: Their symptoms are the results of injuries they have sustained and not reflections on who they are as a person. “Just having that validation that it’s not willful, that it’s not a character flaw, that it’s not a weakness of his, that it’s not him—it’s actually this brain injury that’s very difficult for everyone to manage,” McKee says. “That gives some comfort to people, and it stops the self-blame.”

Although Colt changed significantly after the car accident, the science suggests the damage to his brain from CTE began years earlier. Terry recalled that Colt suffered a concussion while at Colorado as a walk-on before he transferred to Hawai‘i, and, years before that, when he was 12 years old, he suffered a concussion so severe, he began throwing up and had to go to the emergency room.

However, while such concussions are certainly a concern, McHale explains it’s the repetitive hits football players take that are the true roots behind CTE.

“I did not realize that,” Chanel says. “I didn’t know that. So it’s not just about the concussions.”

“It’s the continuous hits,” McKee says. “Those hits can be subconcussive as well as concussive. It’s the cumulative nature of those hits to the head, which over time causes the brain to deteriorate. And he played 17 and a half years, that’s a very long time. And there’s substantial hits that occur at the youth level of football. It all adds up. … That’s why the focus on concussion, while very helpful from the NFL, it’s not addressing the root problem. The root problem is the hits. Even the ones that the players play right through as though nothing happened.”

They do have a solution: “To really make a dent, to mitigate CTE, you have to reduce exposure. Meaning, the less contact, the less likelihood of developing CTE,” McHale says. “As a foundation, we feel very strongly that contact should not be introduced in the sport of football before high school. That could go a long way in reducing the risk for a significant number of people, and we’d see incidents of CTE decrease significantly.”

After the call, the Brennans thank McHale and McKee for their help. They say they feel more peace now. They have a better understanding of just how much damage Colt was dealing with and how remaining sober was more difficult than expected.

Colt’s spirit lives on. The Brennans established the Colt Brennan Legacy Fund in Hawai‘i in order to provide goods and services to people there, as well as contribute money and resources to mental health causes everywhere. A shrine to him remains on a shelf in the living room, at the center of the household. Some of Colt’s ashes have been laid to rest at Pacific View Memorial Park alongside his beloved grandfather, while others were spread in the ocean at the family beach house in Oceanside. On March 20, in a memorial ceremony open to the public, the remainder will be spread in the waves off the coast of Oahu.

Betsy opens a scrapbook and begins leafing through it, one of several they have containing newspaper clippings and pictures from throughout Colt’s life and chronicling just about every game he ever played.

The Brennans think back to when Colt first began playing football. They realize he must’ve been no more than eight years old. “And,” Betsy says, “he probably got hit a lot.”