Recent protests, like the so-called “freedom convoy,” have denounced government action in response to the COVID-19 pandemic by claiming that government mandates like mask and vaccine mandates infringe on their rights and freedoms.

But using the rights discourse in protests is not new.

Many slogans relating to rights and freedoms used by protestors are decontextualized from the history and theory of rights and freedoms, which unfortunately oversimplifies what rights and freedoms really are. As a PhD student in philosophy, with a strong background in ethics and rights theory, I argue that while rights and freedoms language is politically and socially powerful, most people don’t understand what they are, which ones they are entitled to and the morally binding duties they require of others.

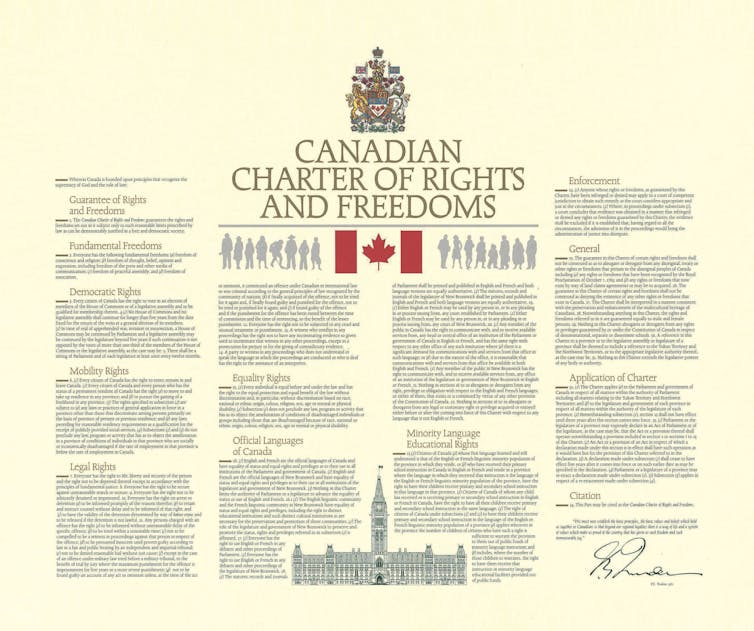

As April 17, 2022, marks the 40th anniversary of the signing of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, it is important people learn what it means to have a right.

The history of human rights

After the Second World War, world leaders came together to develop the Universal Declaration of Human Rights with the goal of preventing future human suffering and atrocities of war.

In the development of the declaration, various ethical theories were used to articulate the kinds of rights that every person should be afforded. At the heart of this document is the right to human equality — “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.”

The Universal Declaration informed the rights legislation in many countries — including the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

And although formal human rights developments have helped governments and organizations understand what qualifies as basic human rights, the separation of rights from its roots in ethical theory has led to many misconceptions about rights and freedoms and, consequently, its misappropriation by protesters for their movements.

Limits to freedoms

Recent protesters claim that COVID-19 mandates restrict their freedom because the government is forcing them to act against their will. They assume that, because we live in a free society, anyone can act however they want.

But this claim assumes that someone’s freedom to act trumps everyone else’s.

Simply by being a member of a society, our rights and freedoms are limited. When someone’s actions have the potential to harm other people, as stated in Section 1 of the Charter, those actions are prohibited or punished.

For example, freedom of expression is protected in Canada, but this fundamental freedom is limited as soon as people’s speech and expression becomes hateful and harmful to specific groups or individuals.

When an action — like hate speech or refusing to follow COVID-19 mandates — is deemed harmful to others, the government can limit one person’s freedom to protect the rights and freedoms of others.

The government declared public health orders for COVID-19 because refusing to follow these recommendations puts others at risk of contracting the virus.

Obligations to protect the rights of others

In some protests, arguing that one has a claim to a certain right obscures how those rights may infringe on someone else’s. If we think that we have a right to something, we need to make sure that it seems plausible that everyone has that right and that the right doesn’t impede the rights of others.

This is further complicated by the question who is responsible for protecting these rights? Because, in short, the answer is all of us. And this universality makes it difficult to determine which rights someone can have in the first place.

A key problem in rights theory is how to balance the different kinds of rights we all hold and how these rights require us to act towards others.

Often, protesters leave obligations out of the picture — including the obligations they have to other people.

Although the rights and freedoms discourse used in protest is impactful, the failure to discuss these nuances increases polarization on controversial issues. For example, one protest may focus on one or two rights and freedoms and the desire to protect those, while another stakes a claim to different rights and freedoms.

When both claim their rights and freedoms are being violated, it becomes difficult to evaluate which side’s rights are worth protecting. And when this happens we often align with the side that most closely resembles our own beliefs.

Rights are not self-exceptional

Instead of discussing who should be protecting people’s rights and freedoms and how they might conflict with the rights and freedoms of others, protest slogans end up perpetuating attitudes of self-exceptionalism and selfishness.

Rights and freedoms were formally established under the assumption that everyone in society matters and that as a society, we need to ensure necessary protections of everyone’s rights. The language used in protests oversimplifies what rights and freedoms are and how everyone has moral obligations to protect the rights and freedoms of everyone in their community.

On the 40th anniversary of the signing of the Charter, it is important to reflect on the rights Canadians share and, more importantly, understand that these rights entail responsibilities to each other.

Perhaps if misunderstandings about rights and freedoms were clarified, there would be a greater sense of unity. And if they matter as much as protesters believe, then we need to evaluate how the support for some rights and freedoms might infringe on the rights and freedoms of others.

Clarisse Paron receives funding from the Nova Scotian government.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.