Chicago’s dirty little habit of locating environmentally toxic industries in minority neighborhoods — or allowing those companies to operate in those communities while they vanish from others — has been known for decades.

So it’s good to see the city last week settle — rather than continue fighting — a U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development investigation that found what is obvious to almost every Chicagoan: that City Hall historically has steered polluters to Black and Brown neighborhoods.

Cheryl Johnson, executive director of People for Community Recovery, one of the organizations whose complaint to HUD led to the investigation, called the settlement agreement “a new roadmap to fight back against environmental racism.”

The settlement is among the final acts of Mayor Lori Lightfoot’s administration.

Not that the former mayor deserves much praise for it.

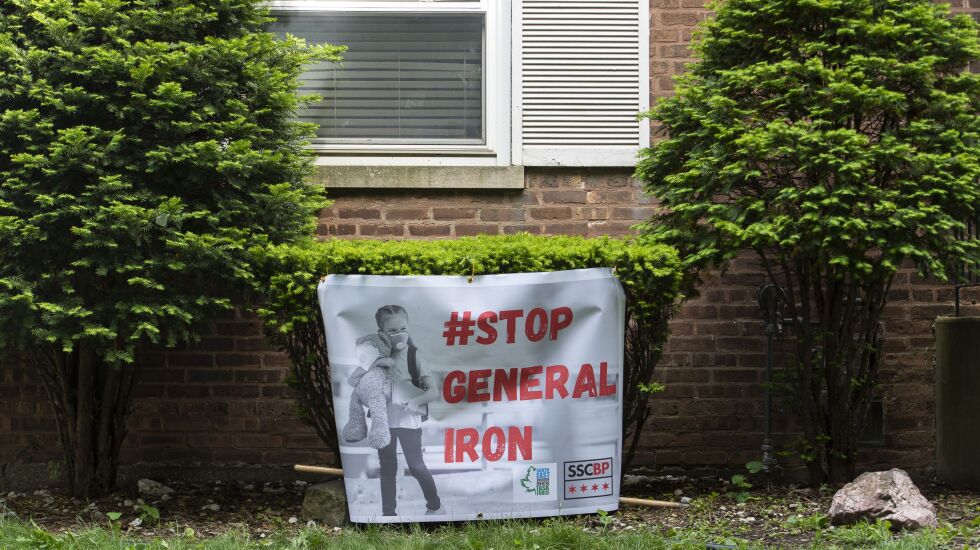

Lightfoot in 2019 green-lit the relocation of troubled metal scrapper General Iron from Lincoln Park to South Deering, a neighborhood of mostly Black and Brown residents — an act that was central to the HUD complaint.

Then she decided to fight the HUD suit, an act that foolishly put hundreds of millions of dollars in future HUD funding to Chicago at potential risk.

“Any allegations that we have done something to compromise the health and safety of our Black and Brown communities are absolutely absurd,” a mayoral spokesperson said then. “We will demonstrate that and prove [HUD] wrong.”

But they didn’t. Which is why the city settled with HUD last week.

Under the three-year, binding agreement with the federal government, City Hall will reform its planning, zoning and land-use practices regarding the location of potential polluters.

The agreement is now up to Mayor Brandon Johnson’s administration to implement. The new mayor last week pledged to “always be steadfast in my commitment to advancing environmental justice and improving the health of our residents and communities.”

Activists such as the late Hazel Johnson — Cheryl Johnson’s mother — fought again harmful polluters on the South Side’s predominantly Black and Brown neighborhoods beginning in the 1970s.

Along the way, she pioneered the national movement against environmental racism.

The settlement is another step in the long road to right environmental wrongs that the Johnsons and others fought.

The Sun-Times welcomes letters to the editor and op-eds. Here are our guidelines.