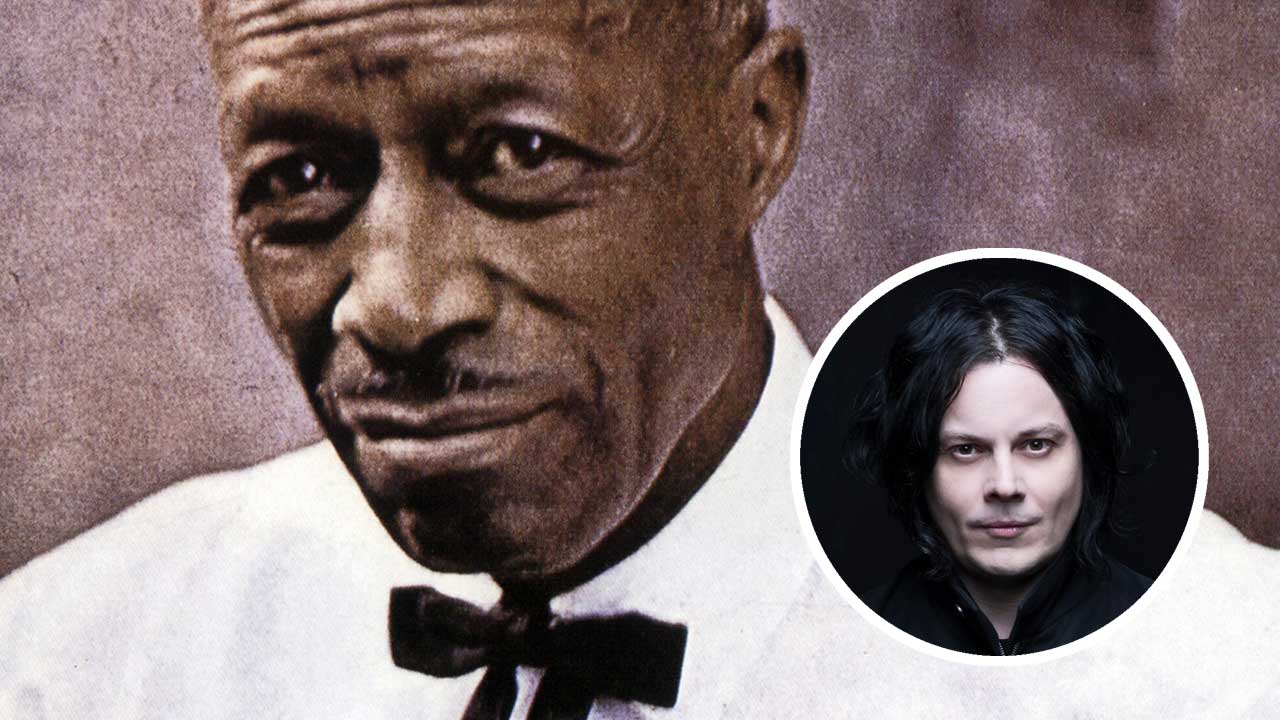

Son House had been in the ground for over a decade when he enjoyed a rebirth through the namechecks of Jack White. The White Stripes bandleader had discovered House through the Scotland-based reissues label Document (“I did whatever I could to get hold of that stuff”) and by 1999, he had fallen sufficiently under his spell to dedicate the duo’s self-titled debut to the late Mississippi legend. “By the time I was 18,” White once reflected, “somebody played me Son House. That was it for me.”

In the 2008 documentary It Might Get Loud, White was still more effusive, dropping the needle on the holler and handclaps of Grinnin’ In Your Face and sitting in a reverential hush. “This [song] spoke to me in a thousand different ways,” he noted.

“I didn’t know that you could do that, just singing and clapping. It meant everything. It meant everything about rock‘n’roll, everything about expression, creativity in art. One man against the world, in one song. It didn’t matter that he was clapping off-time, it didn’t matter there was no instruments being played. All that mattered was the attitude. It became my favourite song the first time I heard it, and it still is.”

For White, House’s negligible finesse didn’t matter, either: he told one interviewer that it was “easy to play like Stevie Ray Vaughan and difficult to play like Son House”, and stood by those comments in a 2012 interview with journalist Brad Tolinski.

“I guess what I meant was, the blues scale is one of the easiest things you can learn on the guitar," he said. "It’s the old cliché: ‘It’s easy to learn but takes a lifetime to master.’ I’m not impressed with somebody playing a blues scale at blinding speed, but I am impressed with Son House when he plays the ‘wrong’ note. Somehow it’s more meaningful to me when I hear him miss a note and hit the neck of his guitar with his slide.”

As well as absorbing his feral slide approach, White also took on House’s material, most notably with the Stripes’ cover of 1965’s signature tune Death Letter. In House’s hands, it had been a scratchy, sparse, spit-and-sawdust lament. When White got hold of it for 2000’s De Stijl, he tooled it up with electric guitars, before delivering the essential version on 2004’s live DVD, Under Blackpool Lights, on which the Detroit duo kick the song’s teeth in. The baton had been passed.