On Nov. 19, the International Space Station (ISS) dodged a potentially dangerous piece of space junk left in orbit from a satellite that broke up in 2015.

The maneuver, which involved the ISS raising its usual orbit of about 250 miles (440 kilometers) above Earth's surface, was the first of its kind in 2024. Without it, NASA officials said the flying object could have come within a perilously close 2.5 miles (4 km) of the space station.

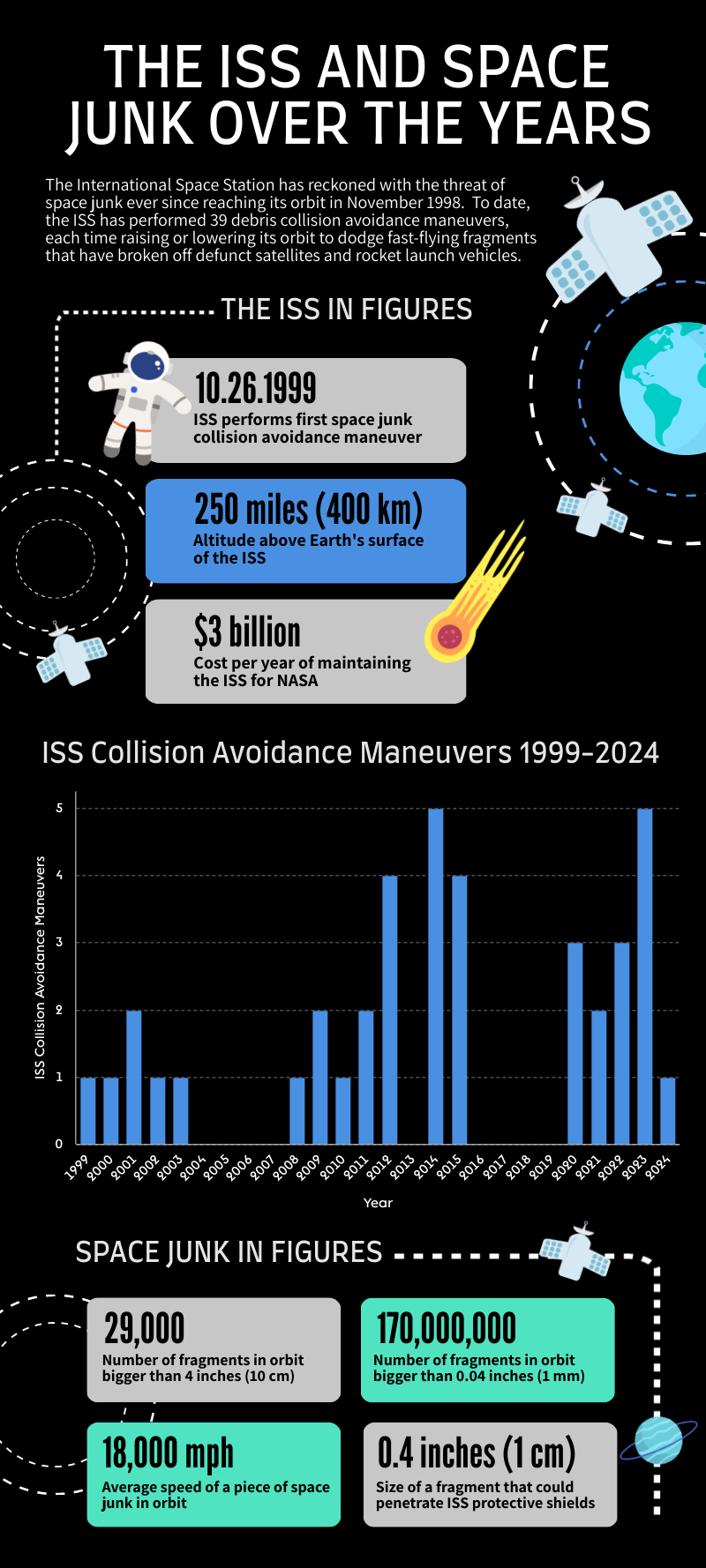

Space junk refers to any fragment of human-made machinery that remains in Earth's orbit after serving its intended purpose. This year's single dodge maneuver — technically called a Pre-determined Debris Avoidance Maneuver — marks a significant drop from the five similar maneuvers the ISS was forced to perform in 2023. It's also fewer than those performed in 2020 through 2022, when the ISS modified its orbit at least twice per year to prevent collisions with space junk.

Astronauts aboard the ISS were lucky that so few pieces of debris came close enough to require maneuvers this year, but that probably won't last, said Hugh Lewis, a professor of astronautics and a space junk modeling expert at the University of Southampton in the U.K. "For all we know, next week there will be three maneuvers," Lewis told Live Science.

Related: Sci-fi-inspired tractor beams are real and could solve a major space junk problem

NASA records show the latest maneuver is the 39th time the ISS has dodged space junk since the first part of the ISS launched in November 1998, and the risk of collisions is increasing every year due to growing amounts of space junk clogging up the sky.

The ISS receives warnings, or "conjunction messages," about incoming space junk from the U.S. Space Force, although that responsibility may soon change hands, Lewis said. A fragment is considered potentially risky if experts forecast it will enter a pizza-box-shaped area that extends 2.5 by 30 by 30 miles (4 by 50 by 50 km) around the ISS. "Anything that goes into that box, then that triggers the next phase," Lewis said, "and they keep going through that process until they've identified if there is a real risk."

The threshold to act on perceived risks is much lower for the ISS than for other spacecraft because there are humans on board, Lewis said. "They're looking at events typically that will be higher [risk] than 1 in 10,000," he said.

It's raining satellites

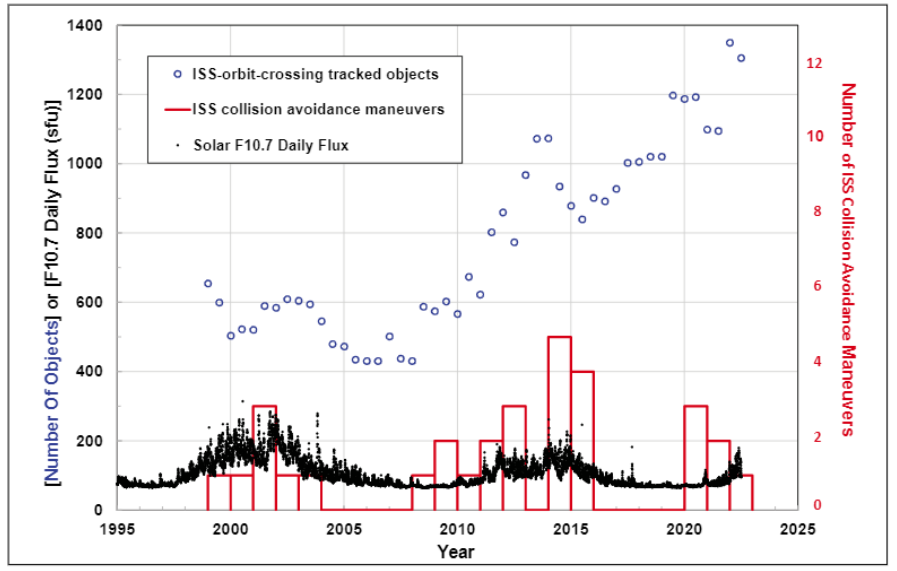

How often space junk approaches the ISS depends on several factors, including the sun's activity and "fragmentation events," when satellites break up in orbit, Lewis said.

Solar activity — including coronal mass ejections, flares and high-speed winds — follows an 11-year cycle and peaks during solar maximum, which researchers say is now underway. At solar maximum, the sun emits a huge amount of energy that gets absorbed by Earth's atmosphere and causes it to expand. This, in turn, increases the drag force on objects in orbits up to 1,200 miles (2,000 km) above Earth's surface, meaning they get pulled toward the planet at a faster rate than in periods outside solar maximum.

The effect of solar activity on space junk is a bit like falling rain, Lewis said. "The rain gets harder, if you like, during a solar maximum," so pieces of debris are more likely to cross the low ISS orbit, he said. "You'd expect to see more maneuvers during the solar maximum."

Yet the sun's fast-growing activity throughout 2024 does not seem to have had a major impact on collision risks with the ISS.

Anti-satellite tests

The impact of solar activity on the ISS is somewhat predictable, but less-foreseeable factors also affect space junk collision risks. Anti-satellite (ASAT) tests, when countries deliberately destroy satellites in orbit, are especially concerning because they produce a huge amount of debris that can linger for long periods, Lewis said.

In 2022, the U.S. and other countries pledged not to conduct ASAT tests, but China, Russia and India have not adopted the resolution. NASA records show that a Russian ASAT test on Nov. 15, 2021, is responsible for almost half — four out of nine — of all ISS collision avoidance maneuvers carried out in the past three years. The satellite in question, Cosmos-1408, was a long-dead Soviet spacecraft launched in 1982.

Another ASAT test on a Chinese weather satellite called Fengyun-1C in 2007 is responsible for at least four collision avoidance maneuvers since then. China shot down the satellite at a height of 500 miles (800 km) above Earth's surface, which is much higher than the 300-mile-high (480 km) orbit of Cosmos-1408 and explains why the ISS had to swerve around Fengyun-1C debris as recently as August 2023, Lewis said.

Space junk orbiting Earth at high altitudes experiences much weaker drag than space junk in low orbits, meaning it lasts longer in orbit before crashing down through the atmosphere, Lewis said. The ISS is still at risk from Fengyun-1C fragments as a result of the weather satellite's high orbit, he said. But "Cosmos-1408 was lower, so the fragments wouldn't have lasted as long."

Clouds of junk

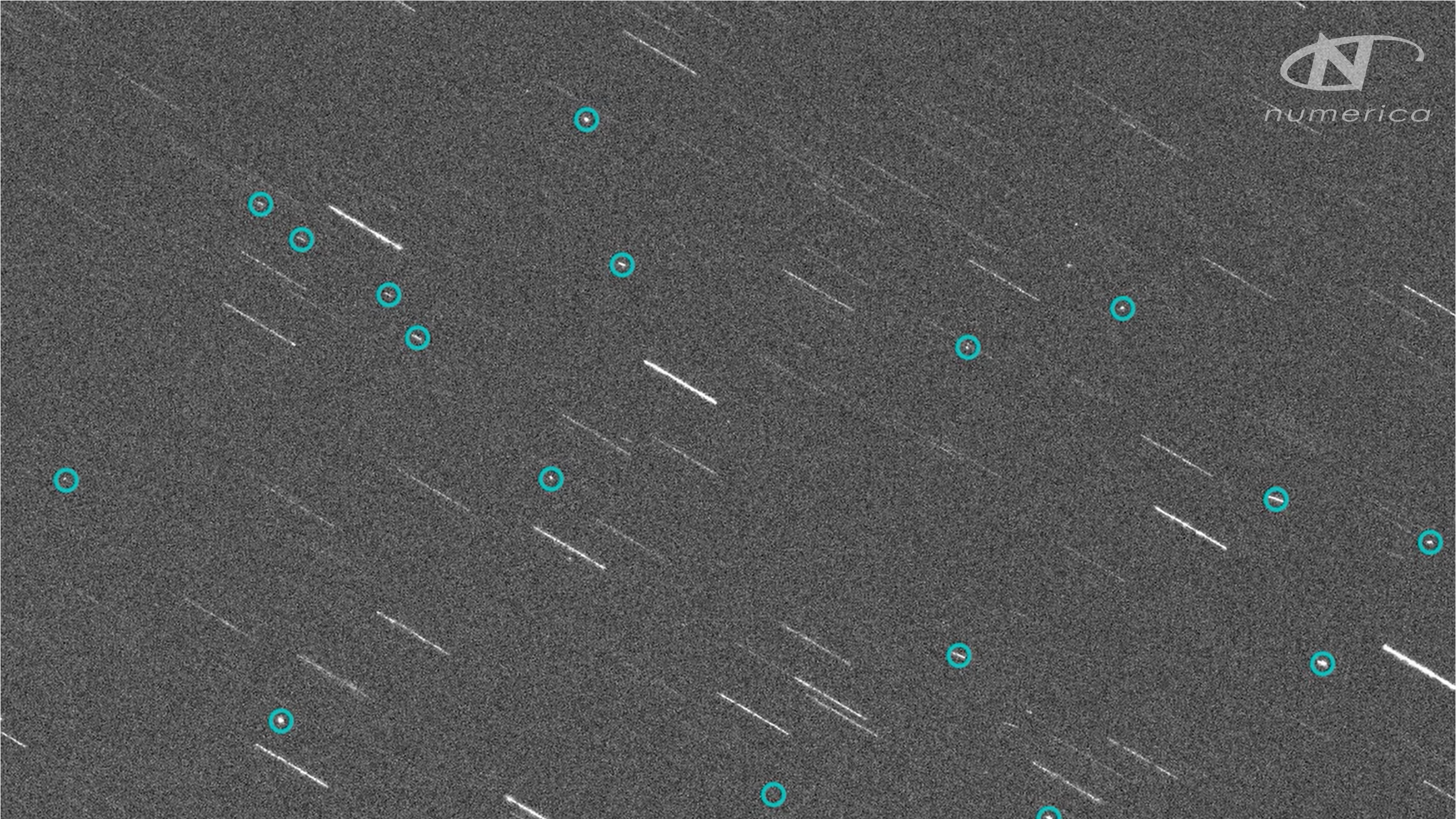

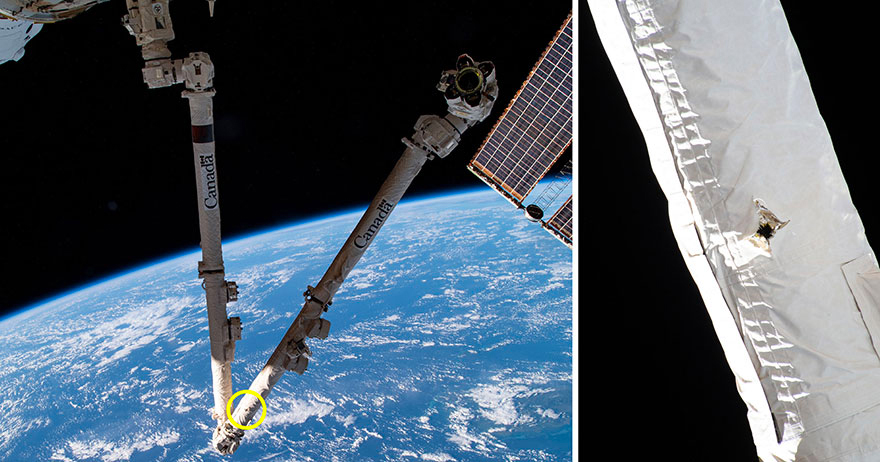

While the ISS has performed only one collision avoidance maneuver so far this year, a rare event involving a cloud of space junk also forced astronauts to take shelter in a spacecraft docked to the space station in June. The incident took place after a defunct Russian satellite broke apart in orbit, sending more than 100 fragments flying dangerously close to the ISS.

In the case of such urgent events, there is no time to change the ISS' orbit. "Those things have to be planned," Lewis said. "You can't just do them by flicking a switch."

The astronauts resumed normal operations shortly thereafter, and there was no damage to the space station — but events like these have the potential to ruin the ISS, Lewis said.

"The fragments are typically of a size that will go through any shielding on the space station, and the space station is a pressurized system in a vacuum," he said. "If you want an analogy, blow up a balloon and stick a pin in it; it's exactly the same process."

The ISS is not the only spacecraft that runs the risk of destruction by space junk. Due to the speed at which objects travel in orbit, any operational satellite could become obsolete if it were to cross paths with a fragment from a long-forgotten rocket. The average piece of space junk reaches speeds of 18,000 mph (29,000 km/h), or almost seven times faster than a bullet, according to NASA.

Even a chip of paint can cause irreparable damage at these speeds, and a 4-inch (10 centimeters) object triggers "a catastrophic fragmentation of a typical satellite," according to the European Space Agency. Around 29,000 objects of this size or larger currently orbit Earth, but those form only a fraction of the more than 170 million pieces — or 9,900 tons (9,000 metric tons) — of debris estimated to be out there.

SpaceX's Starlink satellites illustrate the scale of the problem, Lewis said. Between June 2023 and June 2024, Starlink's fleet of 5,500 satellites made nearly 75,000 maneuvers in total to prevent collisions with space junk. "The number of conjunction messages that they would have received from the U.S. Space Force would have been in the millions," Lewis said.

Looking ahead

NASA plans to retire the ISS in 2031, but until then, the space station will continue to host experiments on behalf of NASA scientists and private contractors. And while it does so, the floating laboratory will probably have to perform many more space junk avoidance maneuvers, Lewis said.

The problem with space junk is that it multiplies: The more space junk there is in orbit, the greater the risk of collisions becomes and the faster the mass of debris grows. Therefore, the best mitigation strategy is to remove satellites that have reached the ends of their missions, Lewis said.

"That has an enormous effect on the future population, because you're removing objects from orbit, so they can't be collision threats," he said. (The ISS will be deorbited at the end of its mission.)

Most space agencies and companies recognize the need for responsible behavior in orbit, Lewis said, and regulations aim to ensure that all actors are held to high standards. "Keeping a clean environment helps their bottom line, because they don't have to make as many maneuvers, [and] they wouldn't lose satellites in collisions," Lewis said. "There is a purpose to those regulations."