A small archipelago off Mexico’s Pacific coast that was home to an island prison colony is undergoing final preparations to become a tourist destination.

For now, even getting to Islas Marias takes a four-hour boat ride.

But Mexico’s government plans to make things easier. It’s putting its navy in charge of tours, the latest function given Mexico’s armed forces by President Andrés Manuel López Obrador.

Beatriz Maldonado already is imagining the voyage. She once was imprisoned between those “walls of water” — as a Mexican writer also confined there described it. Maldonado spent one year there of her six-year sentence for drug and weapons possession, but it was the most painful.

“I lost my smile, my happiness,” she said.

Now 55 and a laundry worker and activist advocating for imprisoned women, she wants to return, hoping for some measure of closure.

The Islas Marias prison colony opened in 1905 on Mother María Island, the biggest of the four Marias islands and the only inhabited one, more than 60 miles off the coast of Nayarit state.

The prison was shut down in 2019, and López Obrador had it converted into an environmental education center.

Now, the government is aiming to make it an ecotourism destination where people can watch sea birds, enjoy the beaches and learn about its history.

López Obrador has announced the island’s airport will expanded, and ferries will be added that can make the trip in two and a half hours.

Visitors will stay in the houses tht once housed prisoners or prison workers . They’re being rebuilt to avoid having to put up new buildings, work that could damage the archipelago’s nature reserve.

Everything could be ready in three months, López Obrador said, though it’s unclear when tours will start.

Some wonder whether Islas Marías might one day a tourist draw like Alcatraz, off San Francisco, or a place like the Panamanian island prison colony Coiba, closed in 2004 and now being reclaimed by the jungle.

Though the government has been criticized for giving many functions to the military, from construction work or oversight of plant nurseries to controlling Mexico City’s new airport, Maldonado sees nothing wrong with the navy taking charge of tourism.

The island no longer is anything like the dirt-floored, warehouse-like prison dorms with five bathrooms for 500 women that Maldonado remembers.

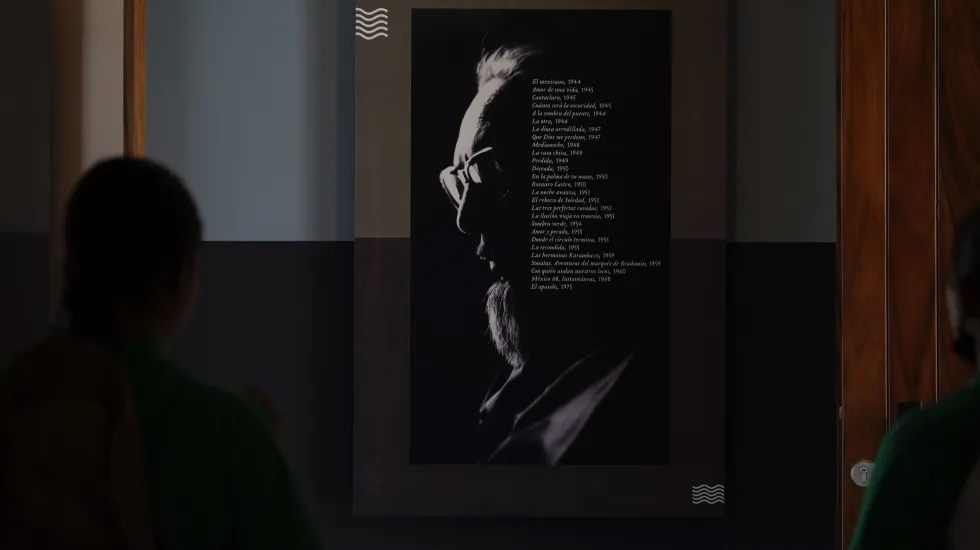

A mural of former South African leader Nelson Mandela, who was held for years in an island prison, welcomes visitors to remodeled buildings, a whitewashed church and a museum featuring writer José Revueltas, who was imprisoned there during the 1930s for his work in the Communist Party.

“What was a hell is becoming a paradise,” López Obrador said.

There was a time it was considered the “tomb of the Pacific.”

In his book “Walls of Water,” Revueltas wrote that the prison was more terrible than he could describe.

Island prison colonies once were common, aiming to make escape nearly impossible.

But Devil’s Island in French Guiana, immortalized in the movie “Papillon,” was closed in 1946. Alcatraz was shut down in 1963. Later, others in Chile, Costa Rica, Peru and Brazil were shuttered.

Prisoners on Mother María Island had to harvest salt and farm shrimp. They tried to make a little money brewing their alcohol from fermented fruits, illegally trading exotic birds or killing boa constrictors to make belts.

In its later years, some prisoners lived with their families in semi-freedom.

That changed when former President Felipe Calderon launched the war on drug cartels in 2006. Hundreds of prisoners were sent there. In 2013, the inmate population reached 8,000.

Maldonado did her time in that era, when women weren’t allowed outside the fences even though they had skills. And they were given barely enough food, according to Maldonado, who said her weight dropped to 45 pounds.

The isolation was the most punishing part, she said, broken only on the 15th of every month, when prisoners were allowed a 10-minute call with a relative.

“The boats came on Thursdays to bring us supplies and letters, and I saw the tears of my mother on the stained pages,” Maldonado said.

Some relatives visited bur rarely because, at the time, that required 12 hours at sea.

A year after Maldonado was transferred to a prison in Mexico City, six people died on the island in a riot over a lack of food.

The island prison was shut down in 2019 because of its high costs: about $150 a day per prisoner, much higher than on the mainland. Also, prison reform had significantly reduced its inmate population.