In April, US lawmakers urged President Joe Biden to ban Chinese-built electric vehicles (EVs), labelling them an “existential threat to the American auto industry”. The proposed ban arose from concerns that Chinese car makers have an unfair advantage due to government financial support.

Following a months-long investigation into digital connections that could enable Chinese spying and sabotage, in recent weeks the Biden administration proposed new rules to ban Chinese-made vehicles. The threats they cite stem from built-in internet connectivity for software updates and various remote controls.

Is the US justified in aiming to ban Chinese-made cars over national security issues, and should Australia follow suit? Remote access and data transmission are an integral part of Chinese cars, but the same is true of modern cars made in most countries.

However, Australia’s relationship with Beijing has been rocky at times. Therefore, it’s vital to understand what data is being sent to China and how any vehicles sold in Australia are vulnerable to remote access and control.

Convencience as a double-edged sword

Many car makers offer remote services, including control over vehicle functions. These features are convenient, but also raise concerns about control, privacy and security.

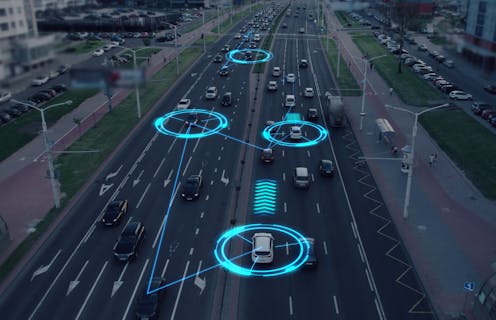

Modern cars are like computers on wheels. They collect data about the car and the driver which can be accessed remotely or during servicing. Computerised control systems and monitoring (also known as telematics) have become widespread.

Regardless of whether the car is electric or petrol-fuelled, the concern is who has access to all that data, and how. If it’s not sent over the internet, but simply downloaded and analysed at the local garage, that’s arguably less concerning.

OnStar, a subsidiary of General Motors launched in 1996, pioneered vehicle telematics and remote connectivity. US law enforcement and intelligence agencies have previously used OnStar’s services to track vehicles, listen to in-car conversations, and even to slow down vehicles during pursuits.

It’s now common for car makers to deliver updates, new features and performance improvements remotely. Volkswagen’s connected service app includes remote start, door lock, vehicle status checks, roadside assistance, vehicle health reports and service scheduling.

Similar apps exist for Ford, Mazda and BMW cars, among others. Earlier this year, police allegedly used an app tracking feature to retrieve a stolen Ford Ranger in Melbourne.

Haval and GWM, two Chinese car manufacturers, also offer connected services for their electric and petrol vehicles in Australia. In some GWM cars, “T-Box” telematics hardware allows the car to connect to the internet. If activated through the manufacturer’s app, GWM ConnectServices collects temperature, battery status, estimated range, mileage, tyre pressure and location. It can also remotely control locks, headlights and other features.

Privacy concerns over internet-connected cars have been widely reported before. But the latest commentary goes beyond this, implying national security risks. Due to so much connectivity, it’s possible for hackers or even nation-states to attack connected vehicles.

Last week, Coalition member Barnaby Joyce expressed concerns China could weaponise remote access to its EVs for “malevolent purposes”. This worry stems from the fact that in Australia, more than 80% of EVs sold are manufactured in China (this includes Tesla models).

Between reality and science fiction

Security experts have raised concerns about China being able to collect driver geolocation and behavioural data, especially in military settings. In the US, car-based espionage concerns have prompted investigations into foreign-made car hardware and software.

To find out whether Chinese cars have actually been used in espionage, governments will need to engage in further scrutiny. This should include increased counterintelligence measures.

Another concern is the remote disabling of vehicles. It is possible to remotely disable a car. Ford filed a patent for remote disabling of services in 2023. Some GWM models currently have built-in alarms and immobilisers that disable a car if unauthorised use is detected.

Moreover, some car manufacturers offer post-theft tracking services, allowing for remote immobilisation. A car equipped with these features could theoretically be hacked by a malicious actor.

Recently, Chechen leader Ramzan Kadyrov accused Elon Musk of disabling his Tesla Cybertruck in Ukraine, where Kadyrov is supporting Russia’s military actions.

This unverified incident hints that a foreign entity could target vehicles over which they have control. However, the possibility of China disabling cars during a trade dispute, cyber conflict or conventional war seems like something out of dystopian fiction.

Who has access to the data?

Ultimately, the worry that nation-states can use highly invasive bits of tech in our cars for spying is not entirely unwarranted.

When you buy a modern car with built-in computers and connected services, you agree that car use data and personal information can be shared with garages and manufacturers. But when we purchase an item, we expect to own it and have full control over its use.

If you’re worried about privacy, take charge. Your best recourse is to know what information your car is collecting, with whom the manufacturer is sharing that information, and where and how that information is being stored and used.

Dennis B. Desmond does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.