A State-funded health insurance scheme, rolled out 14 years ago, was revolutionary at the time. It was aimed at allowing people from the lower economic strata to access high-quality healthcare. Over the years, it brought more services under insurance cover, including transplants, funding immunosuppressants, artificial limbs, high-cost drugs, even investigations, making it the most comprehensive government health insurance in the country. That several thousands of patients have benefited from Tamil Nadu’s Chief Minister’s Comprehensive Health Insurance Scheme (CMCHIS) is indisputable. But its implementation, critics say, is diluted in more than one way, putting both government doctors and patients on a spot.

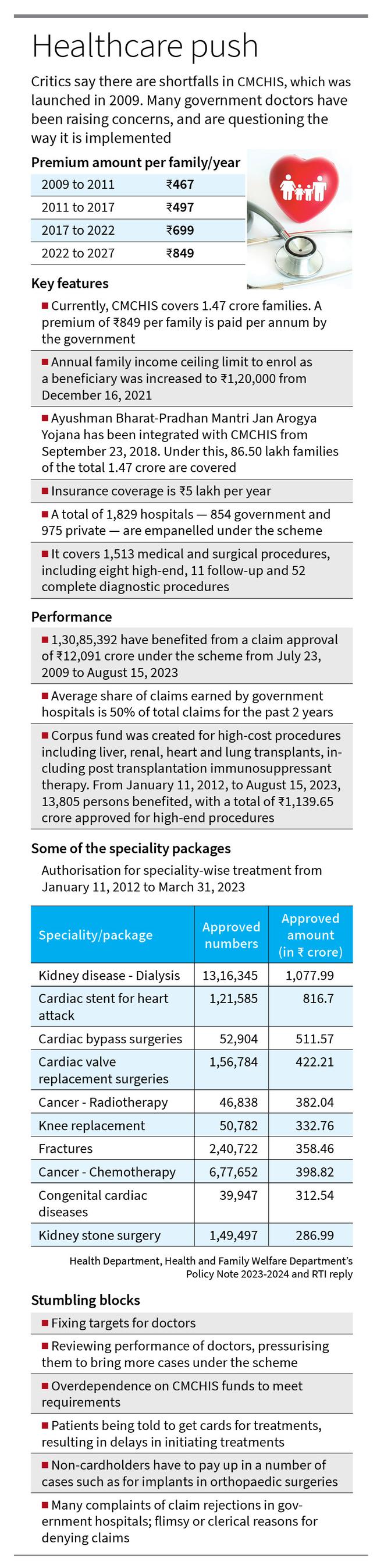

Driven by over-dependence on the scheme-generated funds, government hospitals and their healthcare providers are facing a plethora of issues: targets and periodic performance reviews; pressure to bring more cases under CMCHIS; patients made to run from pillar to post to get enrolled in the scheme; denial of or delays in treatment to non-cardholders; and numerous challenges in getting approval for claims. It was in July 2009 that the government introduced Kalaignar Kapitu Thittam to ensure that the poor and low-income groups get free treatment at private and government hospitals for serious ailments. Today, 1.47 crore families are covered under CMCHIS, and a little over 1.30 crore persons have benefited so far. But there are shortfalls in its implementation. Many government doctors have been questioning the way the scheme is being implemented. “CMCHIS certainly improved healthcare services at government hospitals. Consider this small example. A patient may need 10 doses of an antibiotic costing ₹700-₹800 each. Spending ₹7,000-₹8,000 on an antibiotic for one patient was unimaginable at a government set-up before CMCHIS. The same applies to orthopaedic implants, cardiac stents, cochlear implants and artificial limbs — all made possible because of CMCHIS. But there are certain issues that need to be ironed out,” said a doctor working at a government medical college hospital in central Tamil Nadu.

Dwindling allotments

Hospitals becoming totally reliant on funds generated through CMCHIS and dwindling allotments through the Tamil Nadu Medical Services Corporation (TNMSC) seem to have precipitated the shift from the core objectives of the scheme. As the doctor pointed out, “This has resulted in forcing patients to get CMCHIS cards to even get treated at government hospitals.” A. Ramalingam, secretary of Service Doctors and Post Graduates Association, added, “CMCHIS was started for life-saving procedures and treatments at government hospitals. We, government doctors, accepted it enthusiastically for the benefit of patients as it facilitated the procurement of costly drugs and materials that were otherwise not available. But the scheme was slowly extended to other diseases, and doctors are being pressured to generate money through the scheme. Doctors are forced to act like agents with admitted patients.”

A government hospital doctor said, “On the one hand, doctors are reviewed every week for their ‘insurance performance’ and pressured to generate more money under CMCHIS. Patients are made to run from pillar to post to get their CMCHIS cards so that they can undergo elective surgeries, which were previously done free of cost at the same government hospital. On the other hand, we are seeing a lot of claims denied on flimsy and clerical grounds. ‘Uploaded after 48 hours’, ‘MRI to be prescribed only by a super-specialist’, ‘Seal not clearly visible’ are some of the reasons and the list is endless,” he summed up.

Patient-unfriendly

There are growing instances of patients, who are not enrolled under CMCHIS, being denied treatment or getting delayed treatment at government hospitals. A patient who was diagnosed with stage IV cancer and on palliative therapy was refused treatment because of issues in CMCHIS at a government hospital in Chennai. At another hospital, it took 25 days for a patient, who had a fibroid in the uterus with severe bleeding and anaemia corrected with transfusion, to get admission as she was not enrolled under CMCHIS. She had to return to her native district to get enrolled under the scheme.

“When a patient from a district is sent back to get enrolled under the scheme, it takes at least 10 days for the process to be completed as the village administrative officer needs to sign on the certificate. This is causing delays in initiating treatment,” a young doctor said. In another instance in Chennai, a woman with uterine prolapse was denied admission as she was not enrolled under CMCHIS. A staff member said the woman was later admitted for prolapse repair on the condition that she pay ₹10,000, the doctor said. Doctors recounted several other instances of patients being told to pay up for treatment. “I know two patients who had to pay ₹8,000 for orthopaedic implants at a top government hospital in Chennai,” said an assistant professor. Another surgeon said that while basic medicines are free, patients had to pay in some instances: “In orthopaedics, if surgery is needed, the implant is procured with the insurance money and not through TNMSC. So, if a person does not have coverage, he/she has to buy the implant costing ₹3,000 to ₹4,000...” according to the type of implant needed.”

A number of patients faced issues at private hospitals empanelled under CMCHIS as well. Doctors said there are instances of private hospitals refusing to admit patients because the insurance approval does not come through easily and even if approved, the amount is too low to cover the expenses. Eventually, patients have to pay the rest out of their pockets. Karpagam, 31, is from the Narikuravar community at Devarayaneri near Tiruchi. Her husband was undergoing treatment for kidney disease at private hospitals until he was advised to go in for a transplant. She was selected as the donor. “Once we enrolled in CMCHIS, we were told that only half the insurance amount due for the operation would be used, that too, after we got identity proof and other forms signed by local administration officials. It took us one-and-a-half months to get the signatures. We had to arrange the rest by taking loans,” she added.

The operation took place at a private hospital in Pudukkottai, but Ms. Karpagam’s husband died within a few months of post-surgical complications. “I lost not only my husband and kidney, but also all my savings. I now have to pay back ₹20 lakh in medical loans,” she said.

Patients claim that they are charged more for treatment under the scheme at private hospitals. “I underwent dialysis twice a week due to kidney failure in a private hospital in Tiruchi. Under the scheme, they provided a dialyzer and a blood tubing set, which can be used around eight times. However, I was charged for consumables after four dialysis sessions. The hospital also forced me to buy devices and medicines from their pharmacies at a higher cost,” said M. Sundarraj, a patient.

Claims rejected

Hospitals and departments have become increasingly reliant on funds generated through CMCHIS to meet their needs. Of the claim amount received, 72% is credited to the institution’s account. Of this, 15% is transferred as incentives to doctors, nurses and workers, 40% to the department fund and 17% to hospital development fund, a doctor explained. “Initially, the scheme enabled us to improve our wards and facilities. But gradually, we were told to meet all our requirements through the CMCHIS fund. That is how this wonderful scheme turned into a vicious cycle,” he said.

According to a reply to a question, asked under the Right to Information Act, the government has no information about the number of claims received from government hospitals and rejected. But a number of doctors confirmed that the number of claims rejected were high at government hospitals. “Need more information” and repeated queries from insurance agents are something that they encounter regularly. “No administrator questions the insurance company. Rather, they question us. Decisions taken by the heads of super-speciality departments on surgeries or change of plans are questioned. They make repeated queries and ask for more information on a daily basis. If the information is not updated within 48 hours, they reject the claims,” a senior surgeon said.

If a patient who suffered a stroke is wheeled into emergency care, it takes at least 12 to 24 hours to stabilise and evaluate him/her during which imaging and opinion from neurologist/ neurosurgeon are obtained, a doctor said, adding, “In such a situation, will I focus on treating the patient or will I ask the attendant for CMCHIS card? Or will I be able to upload the details for raising pre-authorisation in 48 hours?”

A physician quickly added, “Not even 50% of the cases get approved. Whatever is approved comes after unwarranted and repeated scrutinies. Even in approved cases, the final amount credited is less than 20% of the total package value, especially for medically managed cases.”

“One rule is that patients, at the time of admission, should have the CMCHIS card. If they receive the card after admission, it becomes one of the grounds for rejection. Do all eligible persons have the insurance cards in Tamil Nadu? Many do not know how to obtain the cards,” said a doctor who is well-versed in the functioning of CMCHIS.

He added that if a person is admitted for surgery for a fracture, doctors need to do an evaluation for co-morbidities. “The person might have diabetes or hypertension or seizures which need to be treated and brought under control. We need to get fitness for anaesthesia only after this. So, if there is a delay from the date of approval and surgery, the claim is denied. We have to submit not only discharge summary and investigation reports but also the photographs of the suture scar and the patient inside the ward,” he said.

One surgical department in Madras Medical College was denied claims to the tune of ₹80 lakh, while another department in Government Stanley Medical College Hospital was denied ₹50 lakh in claims, he said. Government doctors say they face a lot of difficulty in obtaining pre-authorisation approval for procedures from the insurance company representatives. “As government hospitals do not have dedicated staff to handle insurance-related matters, doctors are handling them, besides their routine duties. Obtaining pre-authorisation consumes a lot of time,” said a government doctor from Coimbatore.

In many departments, insurance work is allotted to postgraduate medical students. “In the process, they lose their training or operation theatre days and end up doing clerical jobs,” The filled-up insurance claims are handed over to a ward manager but as doctors, we need to sit in office rooms and spend at least two hours a day on insurance-related work, instead of focussing on patient care,” a surgeon added.

At government hospitals, assistant professors, doctors and postgraduate students are made to coax patients into bringing their cards and to take forward the process of getting approval in the insurance portal. In this hurry, clinical work, patient care and academic activities are compromised, doctors said. A senior doctor wanted the government to do away with the practice of fixing targets for procedures. There is a lot of pressure on doctors, and as a result, they expend a lot of time and energy on arranging for procedures, including procuring consumables, rather than on paying attention to patient care. “Government medical college hospitals are teaching institutions where the focus should be on improving the facilities so that doctors get trained in performing advanced procedures. But the current approach is to turn government hospitals into profitable institutions. Many times, very needy patients without cards come for treatment and doctors face difficulty in handling such situations when the approach is to make these hospitals profitable institutions,” he said.From department-wise reviews on the CMCHIS performance at medical college hospitals, officials are conducting unit-wise reviews. Are faculty-wise reviews next, a doctor asked. Another issue is an uneven distribution of funds as not all departments can generate funds through CMCHIS.

K. Senthil, president of Tamil Nadu Government Doctors Association, said there are issues of targets and delays in treatment for want of cards. “We should go back to the original Kalaignar Kapitu Thittam and increase the role of the private sector,” he said. “The government spends at least ₹1,200 crore in premium a year. Instead, it can directly invest a sum in government hospitals,” a senior doctor added. SDPGA has already demanded that the government ask people to bring their insurance cards for getting in-patient treatment at government hospitals and establish separate teams for implementing the scheme.

In a written response, officials of the Health Department, while explaining the guidelines for claims processing, said that if there was any genuine delay in submission of card or pre-authorisation request, it was considered on the basis of merits. Periodic reviews by officials are done to streamline the implementation of the scheme. A Health Department official said, “In our State, healthcare service is provided free in all government institutions, therefore any patient, even if he/she is not a beneficiary under the scheme, can approach government institutions and get treatment for all types of illnesses free of cost.” An official of the Tamil Nadu Health Systems Project said a grievance redress mechanism is in place, with meetings held every Monday with the stakeholders-third party administrators, institutions and the head office team. At these meetings, grievances about pre-authorisation and denial of claims, raised by institutions, are looked into. “This is a great and sustainable scheme that is running smoothly. The participation of government hospitals in the scheme stands at 53%,” he said. He added that there are definitely room for improvement, and it was a continuous process.

(With inputs from Nahla Nainar and Ancy Madonna Donal in Tiruchi and Wilson Thomas in Coimbatore.)