In electoral campaigns, election signs help candidates market themselves. But does the language of an election sign matter in a multilingual society?

This question is relevant in Québec, especially as the province begins its fall election campaign.

While Québec is predominantly French-speaking, the population of potential voters in Québec is linguistically diverse. According to the 2021 census, 93.7 per cent of Quebecers know French, but 28.2 per cent speak a language other than French at home. And the majority of the population knows more than one language — 14.5 per cent know three or more. This makes Québec the province with the most bilingual and multilingual people in Canada.

Languages on election signs

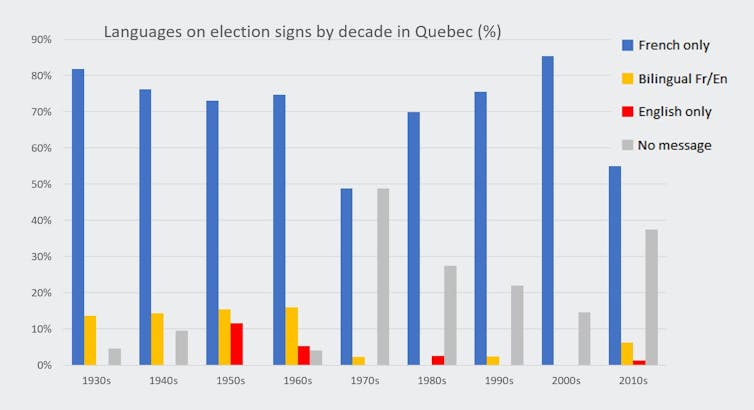

Despite that linguistic diversity, Québec’s political parties post few signs in languages other than French during campaigns. In fact, our research — yet to be published — shows that over the last 100 years, less than 10 per cent of political signs posted in the province were bilingual or in English.

The majority of signs were in French or did not convey a particular message other than the name of the candidate, party or riding.

Our findings also show that the presence of English on election signs has fluctuated over time. For example, 22 per cent of signs had some English on them in the 1950s and ‘60s. This percentage fell to 2 per cent from the 1970s to 2000s, followed by a timid resurgence of English in the 2010s.

In translation studies, we say that translation not only serves as a textual indicator of meaning, but also as a sociopolitical indicator. This is clearly the case when it comes to election signs.

The overall disappearance of English from election signs coincides with the redefinition of the political and social balance of power in Québec since the 1960s.

One might assume that posters are almost exclusively in French because of the Charter of the French Language, but in no way does it prevent political advertising in other languages. The explanation here lies in the context rather than the law.

Should political parties post signs in different languages?

As the vast majority of Quebecers know French, political parties could easily decide to post their election signs in French only. But it is also true that people tend to prefer content in their mother tongue.

That fact however doesn’t mean a political party would gain votes by posting signs in English or other languages.

To find out how Quebecers perceive election signs in different languages, we conducted a survey on electorate language preferences — the results of which will soon be published in Meta. Our survey consisted of multiple-choice questions where participants were shown several hypothetical unilingual and bilingual election signs.

Perception of French and English signs

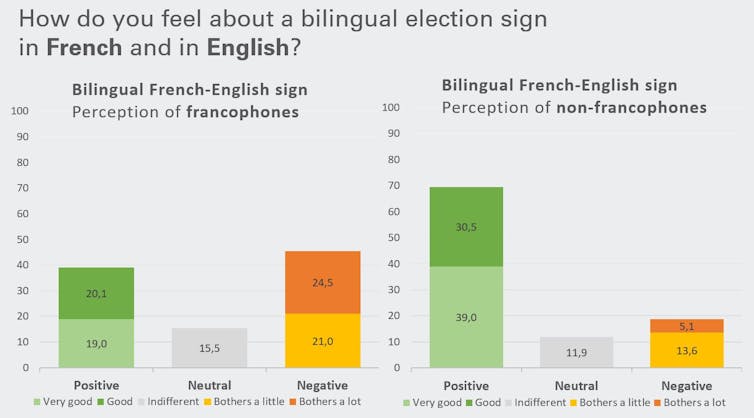

The vast majority of Francophones (82.9 per cent) had positive feelings towards a unilingual French poster. Among non-Francophones, 61 per cent felt the same.

For a sign in English only, a mere 4 per cent of Francophones liked it, compared to 18.7 per cent of non-Francophones. When it came to bilingual (French-English) signs, 39.1 per cent of Francophones and 69.5 per cent of non-Francophones had positive feelings.

This shows that what bothers Québec voters is not so much the presence of English on signs, but the absence of French — English-only signs bothered 91.5 per cent of Francophones and 61 per cent of non-Francophones.

Perception of signs in other languages

When presented with signs with a message in a foreign language, participants generally felt more positively towards those showcasing languages closer to French like Spanish, Italian and Portuguese — especially compared to those using a different script like Arabic, Mandarin and Russian.

The bilingual French-Spanish sign was the most widely accepted. Spanish is also the most widely understood foreign language in the province with a total of over 450,000 speakers. So what seemed to bother participants was their inability to understand a language.

However, a sign in Inuktitut generated very positive feelings across all Quebecers, especially when the sign was bilingual with French.

Should political parties post signs in multiple languages?

Although our participants’ perceptions of hypothetical signs don’t necessarily translate into who they will vote for in real situations, they exemplify the linguistic preferences of the Québec electorate.

Francophones prefer by far French-only signs and non-Francophones have similar positive feelings towards French-only signs and bilingual French-English signs, the latter being slightly preferred.

Our findings suggest that Québec politicians who wish to put up provincial election signs in languages other than French should do so with caution.

Bilingual signs and signs in other languages could be used strategically in locations chosen with care, taking into account where said languages are actually spoken.

It will be interesting to see what political parties actually do during the 2022 campaign, especially in the context of Bill 96 and the newly released census data showing a decline of French.

Signs in languages other than French could be seen as an outstretched hand in yet another episode of linguistic tensions, but also as an indicator that French is indeed losing ground.

Marc Pomerleau receives funding from Fonds d’aide institutionnel à la recherche, Université TÉLUQ.

Esmaeil Kalantari does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.