Copper is one of those substances we take for granted — until we start adding new wiring to the house, looking for a power cord to the children's computer, or maybe buying antique copper pots.

Or, malevolently, when someone cuts the wires from your car battery to your spark plugs.

But copper is a key element (an actual element; periodic table symbol Cu) in the evolution of how the world migrates from the World Wide Web to artificial intelligence.

Related: Silver is shining brighter than gold this year

This year, money has been moving into copper as part of the continuum of the process that results in power generation.

And the demand for power generation is growing because of all the energy needed for data centers, where artificial intelligence applications are trained and live.

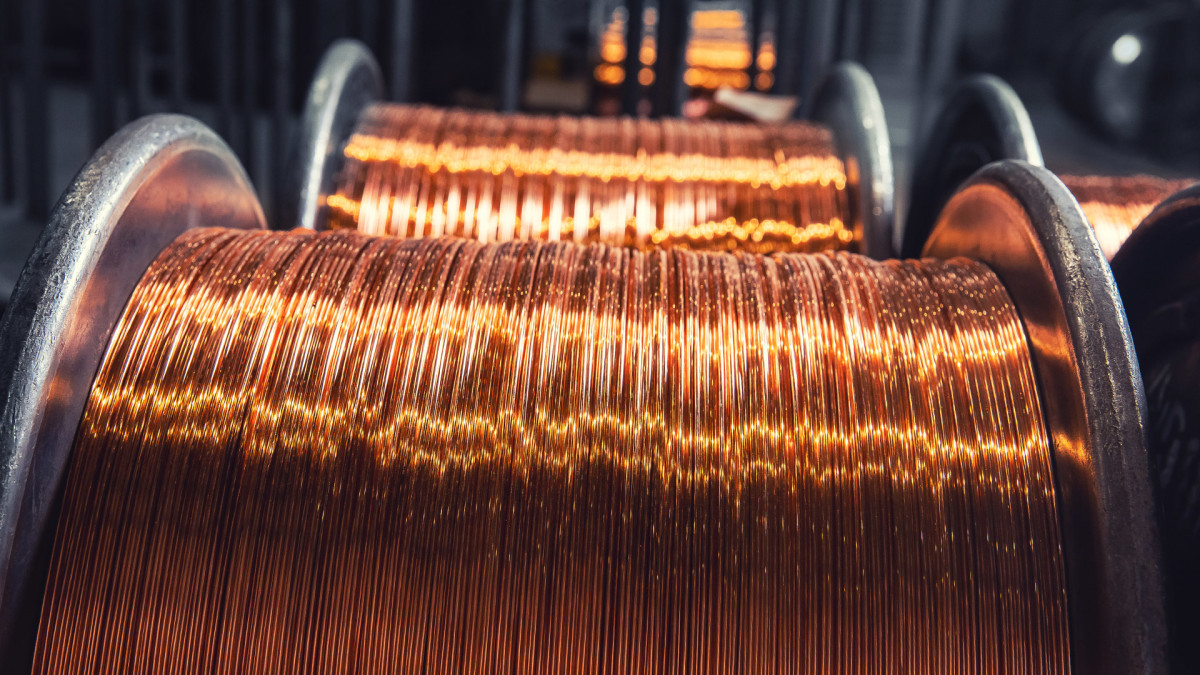

Getting power to where it needs to be requires generators, transmission lines, transformers, switches, regulators, and and various measuring devices, and that means miles and miles of wiring connecting everything together.

That wiring is made of copper.

Shutterstock

Copper: A long history with humans

Copper has been part of human life for thousands of years.

An axe with a copper blade was found with the mummified body of Ötzi, whose 5,200-year-old remains were found in the Alps between Austria and Italy in 1991.

The blade was sharpened regularly, but it was low technology. Ötzi may well have known that copper was too soft a metal for a weapon.

Later, artisans combined copper with tin and other metals to make a stronger metal — bronze. They also used copper in ceramics, paints and other products.

Copper: a gift to economic development

Since the 19th century, people involved in developing electric utilities have known that copper has another important attraction. It's a terrific conductor of electricity beloved by power companies because it's relatively cheap.

The journey for copper starts at the mine when ore is extracted. The ore is crushed and run through chemical baths to become a concentrate, which is ultimately smelted into the red metal we know today and processed into those miles and miles of wiring.

It has one big drawback. Finding decent deposits means searching all over the globe.

Copper: welcome appreciation from investors

As of May 3, the price of copper on the London Metal Exchange and the Chicago Mercantile Exchange is up more than 17% this year. The Chicago close on May 3 was $4.557 a pound, up 1.6% on the day but down 2.9% from a 52-week high of $4.695 on April 30.

The U.S. Copper Index Fund (CPER) , organized to invest in the metal, is up 17.5% on the year.

But copper, like any industrial commodity, gets hammered in a slowdown. It fell below $2 a pound in 2008 during the financial crisis and to $2.16 in 2020 during the pandemic.

Mining company stocks are also up this year. The Global X Copper Miners exchange-traded fund (COPX) is up 24.4% this year—9.9% so far in the second quarter.

The ETF's holdings include giants like Newmont (NEM) , Anglo-American (NGLOY) , Brazilian-based Vale (VALE) , and Freeport-McMoRan Copper & Gold (FCX) .

So far, Anglo-American is the biggest winner in the group. Its U.S. shares are up 45% in 2024.

Freeport-McMoRan shares are up 18.5% and 7.3% so far in the second quarter.

One of the world's largest copper producers, Freeport has the Grasberg complex as its primary source in the mountains of New Guinea in eastern Indonesia.

The complex is located just 2 1/2 miles (4 km) west of the 16,024-foot Puncak Jaya, the tallest mountain between the Himalayas and the Andes.

For nearly 30 years, in a hostile physical, natural, and complicated-and-often-unsavory political environment, Freeport produced billions of pounds of copper at Grasberg. And from the copper ore, the Grasberg deposits have yielded millions of ounces of gold — as a byproduct.

The open-pit mine is a mile wide and more than 1,800 feet deep. It can be seen from space.

Those deposits are largely played out. Freeport-McMoRan is now extracting its ores from veins it found deep underground.

Copper: Boom-and-bust cycles

To be sure, copper is subject to boom-and-bust cycles.

A slump in China that began with the Covid-19 pandemic depressed the country's need for copper. That left copper prices stagnating for several years.

It's true that mining copper — or any mineral — is, at the very least, a messy business involving the destruction of local environments, the creation of fantastic amounts of waste, and the use of toxic chemicals.

But copper is an essential material needed to build and expand modern economies. That helps explain why China has consumed as much as 30% of global production.

Copper's gains are good for copper companies, investors, miners (theoretically), technology companies, and even for consumer health in trace amounts.

And heaven knows, Tesla (TSLA) , all the Chinese electric-vehicle makers and companies rushing to make EVs need copper wiring.

That assumes enough copper can be produced to meet what's expected to be strong — if not soaring — demand at least over the next few years and probably longer.

More on forces affecting markets

- Sam Altman and the failure that ultimately led to ChatGPT

- Nvidia set to capture billions as big tech boosts AI spending

- Bearish Bets: 3 Well-Known Stocks You Should Consider Shorting This Week

In fact, Meta Platforms (META) CEO Mark Zuckerberg said in January that the company expected to buy 350,000 Nvidia H100 graphics processing units by the end of the year.

That means demand for more copper because one H100 GPU uses some 700 MW of power per year. That's roughly the same as a typical house.

And Nvidia is shipping these units as fast as its manufacturing teams can make them and is getting ready to produce a new generation of faster GPUs.

Its next-generation GPU, code-named Blackwell, will have 208 billion transistors and will be faster, less costly to operate, and more energy efficient, the company promises. The H100 unit has only 80 billion transistors.

How does that translate into power demand?

Related: Nvidia set to capture billions as big tech boosts AI spending

Developers of a data center proposed for the Portland, Ore., area forecast needing 60 megawatts of power a year, enough to power 45,000 home annually, the Post said. The developers are now looking at "off-the-grid, high-tech fuel cells that convert natural gas into low-emissions electricity."

Electric utilities are reworking their forecasts of power demand. They now expect they will need much more power to meet the demand from the massive data center developers.

These centers run 24 hours a day to power the computers and the cooling systems needed to prevent servers from overheating and crashing.

So, that means more demand for copper.

By the end of 2023, Schneider Electric, (SBGSY,) the French specialist in digital automation and energy management problems, estimated that the power required to run artificial intelligence facilities was as big as all the power consumed on the island of Cyprus.

And it's growing at a compounded rate of 26% to 36% a year.

This means that what's being used now will double in just a few years, and data centers alone will use as much power as Iceland.

And that means more demand for copper.

Copper: Could demand outstrip supply?

Sounds great for the producers and refiners of copper. However, the demand might prove so great that it will outstrip both copper production and the ability of power companies to deliver electricity.

Analysts at Citigroup say global demand for copper will exceed global production this year, The Wall Street Journal reported. The shortfall will last for the next three years.

Plans for new data centers already under construction in North Virginia mean stretched capacity for local utilities — the equivalent of several nuclear plants, the Washington Post reported.

Related: Analyst who correctly forecast gold's rally unveils new price target

Georgia is so worried about power shortages it's rethinking offering data center developers incentives to locate facilities there.

Still and all, it's possible that the fears of power shortages won't materialize.

Projects can get delayed by permitting processes, environmental reviews, and, of course, lawsuits.

Nvidia, Microsoft, Alphabet, and others have armies of engineers who figure out how to minimize the power demands of their GPUs.

But all that means is that the demand for copper will be strong in the foreseeable future. It may not grow as fast as enthusiasts think, but it will be steady at the very least.

That means more demand for copper, and potentially, higher prices.

Related: Veteran fund manager picks favorite stocks for 2024