An Irish woman has been inspired by the Guardian to return her late father’s collection of 19th-century African and Aboriginal objects to their countries of origin.

Isabella Walsh, 39, from Limerick, has contacted embassies and consulates in Dublin and London to repatriate 10 objects, including spears, harpoon heads and a shield, after she read about other cases in the newspaper.

The objects had belonged to her father, Larry Walsh, an archaeologist and curator of the Limerick Museum, who had always cherished them due to his passionate interest in African and Aboriginal cultures.

But he also believed that such objects belonged to the peoples from whom they had originated.

His daughter, a model-maker and sculptor in the film industry, said: “It was one of my father’s final wishes that the artefacts be repatriated. He passed away 10 years ago and I’ve had them in storage since then. I didn’t really know where to begin. It’s taken me a long time to just process his passing and all the changes that have happened in my life … He was adamant that this was to happen.”

She added: “I appreciate and love the beauty of these objects and the craftsmanship … But they’re not culturally relevant to me.”

She had no idea how to repatriate the objects until she read a Guardian article in May about an American who had returned 30 antiquities to Italy. He in turn was inspired by another report about a man who sent back 19 antiquities to their countries of origin amid growing coverage of looted ancient artefacts.

Jay Stanley handed over vases and figurines dating from the sixth to the third centuries BC, found at the home of his late father, after reading that John Gomperts, from Washington, had repatriated ancient artefacts that he had inherited from his grandmother to Italy, Greece, Cyprus and Pakistan.

Each of them had turned for guidance to Dr Christos Tsirogiannis, a guest lecturer in the department of archaeology at the University of Cambridge. Tsirogiannis also leads research on illicit antiquities trafficking for the Unesco chair on threats to cultural heritage at the Ionian University in Corfu, Greece.

Over 17 years, he has identified more than 1,700 looted objects within auction houses, commercial galleries, private collections and museums, alerting police authorities and governments and helping to repatriate items.

In 2018, when Sotheby’s in New York advertised the sale of an ancient Greek bronze horse, Tsirogiannis identified through photographic evidence its links to a disgraced British antiquities dealer. In 2020, Sotheby’s lost its legal challenge and Greece’s culture minister described the court’s ruling as a victory for countries seeking to reclaim antiquities.

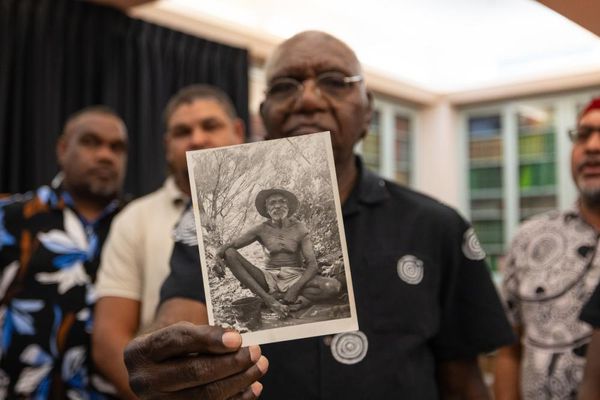

Walsh wrote to Tsirogiannis: “I do not know how to go about this – any advice or assistance you can offer would be of great help.” Now, with his guidance, she is organising the return of artefacts to Sudan, South Sudan, South Africa and Australia.

In a letter to the South African authorities, for example, she wrote: “I am getting in contact regarding the return of several Zulu/South African historical artefacts to your country … It was one of my father’s final wishes that these artefacts be returned to their cultural origins, ideally to be housed in their respective national museums.”

The items include two Zulu clubs. Carved from a dark hardwood, these were designed as hunting weapons.

Mabet van Rensburg, counsellor political at the South African embassy in Dublin, wrote to her: “This is indeed a lovely gesture.”

Another wooden club or stick is an Aboriginal example that Walsh plans to return to Australia. It is similar to one in the British Museum, Tsirogiannis said.