Ivan F Boesky, the infamous Wall Street trader who inspired Michael Douglas‘s Gordon Gecko character in the movie Wall Street, has died at the age of 87.

His daughter Marianne Boesky told The New York Times on Monday that Broesky died in his sleep. No cause of death was given.

The son of a Detroit delicatessen owner, Boesky was once considered one of the richest and most influential risk-takers on Wall Street. He had parlayed $700,000 from his late mother-in-law’s estate into a fortune estimated at more than $200 million, hurtling him into the ranks of Forbes magazine’s list of the 400 richest Americans.

But once implicated in insider trading, Boesky cooperated with a brash young U.S. attorney named Rudolph Giuliani in a bid for leniency, uncovering a scandal that shattered promising careers, blemished some of the most respected U.S. investment brokerages and injected a certain paranoia into the securities industry.

Working undercover, Boesky secretly taped three conversations with Michael Milken, the so-called “junk bond king” whose work with Drexel Burnham Lambert had revolutionized the credit markets. Milken eventually pleaded guilty to six felonies and served 22 months in prison, while Boesky paid a $100 million fine and spent 20 months in a minimum-security California prison nicknamed “Club Fed” beginning in March 1988.

After Boesky’s arrest, accounts widely circulated that he had told business students during a commencement address at the University of California at Berkley in 1985 or 1986, “Greed is all right, by the way. I want you to know that. I think greed is healthy. You can be greedy and still feel good about yourself.”

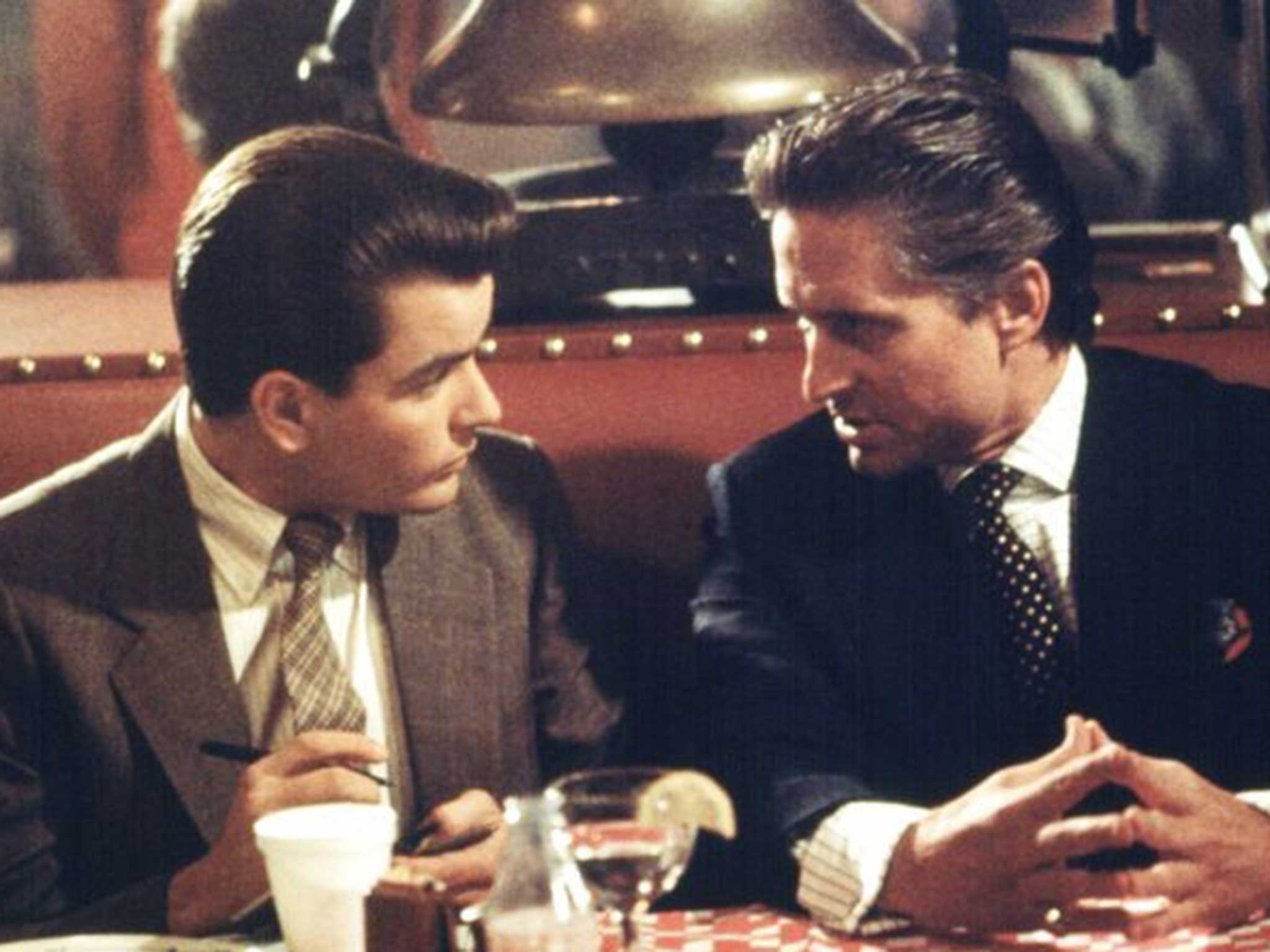

The line was memorably echoed by Michael Douglas in his Oscar-winning portrayal of Gordon Gekko in Oliver Stone’s 1987 film “Wall Street.”

“The point is, ladies and gentlemen, that greed, for lack of a better word, is good,” Douglas tells the shareholders of Teldar Paper. “Greed is right. Greed works. Greed clarifies, cuts through, and captures the essence of the evolutionary spirit.”

Boesky said he couldn’t remember that “greed is healthy” line and denied another quotation attributed to him in the 1984 Atlantic Monthly, in which he said climbing to the height of a huge pile of silver dollars would be “an aphrodisiac experience.”

While he usually worked 18-hour days, the silver-haired, lean and not-too-tall Boesky also certainly lived a life of opulence. He wore designer clothes, traveled in limousines, private airplanes and helicopters and revamped his 10,000-square-foot Westchester County mansion with a Jeffersonian dome to resemble Monticello.

“There was a very substantial amount of materiality available,” Boesky said during his 1993 divorce proceedings. “We had places in Palm Beach, Paris, New York, the south of France.”

Boesky was an arbitrageur, a risk-taker who made millions by betting on stocks thought to be the target of corporate takeovers. But some of his tips came from within the mergers and acquisitions departments of Drexel Burnham Lambert Inc. and Kidder, Peabody & Co.

Dennis Levine of Drexel and Martin Siegal of Kidder, Peabody fed Boesky confidential information in return for a promised cut of profits of either 1 or 5 percent.

Boesky paid Siegal $700,000 in three installments, with a courier delivering briefcases full of cash at three clandestine meeting on a street corner and in the lobby of the Plaza Hotel. Boesky had made millions on Siegal’s tips, which included word that Getty Oil and Carnation Co. were ripe for takeovers.

Levine was arrested before his payout could come, tripped up by his own insider trading. Facing harsh penalties under the government’s racketeering statutes, Levine told everything. And Boesky sang as well, providing information leading to convictions or guilty pleas in cases involving former stockbroker Boyd Jefferies, Siegel, four executives of Britian’s Guiness PLC, takeover strategist Paul Bilzerian, stock speculator Salim Lewis and others.

The biggest fish was Milken, the pioneering financier who had transformed the capital markets in the 1970s with a new form of bond that allowed thousands of mid-sized companies to raise money.

In the 1980s those “junk” bonds were used to finance thousands of leveraged buyouts, including of Revlon, Beatrice Companies, RJR Nabisco Inc. and Federated Department Stores, making Milken a hated and feared figure on Wall Street.

The financier and philanthropist was indicted on 98 counts, including securities and mail fraud, insider trading, racketeering and making false statements. Prosecutors said Milken and Boesky conspired together to manipulate securities prices, rig transactions and evade taxes and regulatory requirements.

Milken eventually pleaded guilty to six securities violations, including telling Boesky he’d cover any losses he suffered trading the stock of Fischbach Corp., a takeover target at the time.

Prosecutors said Boesky’s cooperation provided the government with the most information about securities law violations since the legislative hearings that led to the 1933 and 1934 Securities Acts.

When John Mulheren Jr. feared he was about to be implicated, the Wall Street executive loaded an assault rifle with the intent of killing Boesky and Boesky’s former head trader, police said. Mulheren was seized en route.

At trial, Mulheren’s attorney, Thomas Puccio, called Boesky as a repeat liar and “pile of human garbage” who was motivated to say anything to fulfill his promise to assist federal authorities in exchange for leniency.

“If there ever was a person to whom the title Prince of Darkness could be applied, Ivan Boesky is that man,” Puccio said. “The king of greed, a person who stood for nothing except his own ambition, his own greed.”

The jury convicted Mulheren, but his conviction was later overturned. Other convictions were reversed as well — those of GAF Corp. and a senior executive, five principals of Princeton-Newport Partners and that of a former Drexel trader.

The reversals bolstered the arguments of free-traders who argued that Wall Street had been victimized by a publicity-seeking federal prosecutor using racketeering statutes usually reserved to combat organized crime. The government had previously done little to police insider trading, and some said it should be legalized.

But no one could defend payoffs involving suitcases full of cash. Levine, writing in the pages of Fortune after his release, said he couldn’t understand why Boesky would risk so much by engaging in something so clearly illegal.

“And I don’t know why Ivan engaged in illegal activities when he had a fortune estimated at over $200 million,” Levine wrote in 1990. “I’m sure he derived much of his wealth from legitimate enterprise: He was skilled at arbitrage and obsessed with his work. He must have been driven by something beyond rational behavior.”

At his 1987 sentencing Boesky’s lawyer quoted his psychiatrist as saying Boesky “has begun to recognize that he suffered from an abnormal and compulsive need to prove himself, to overcome some sense of inadequacy or inferiority that is rooted in his childhood.”

Three years after his release from a Brooklyn halfway house in April 1990, Boesky and his wife Seema divorced after 30 years of marriage.

Claiming he had been left penniless after paying fines, restitution and legal fees, he won $20 million in cash and $180,000 a year in alimony from her $100 million fortune. He also got a $2.5 million home in the La Jolla section of San Diego, where he lived with his boyhood friend, Houshang Wekili.

Ivan Frederick Boesky was born in Detroit in 1937 into a family of Russian Jewish immigrants. Boesky said he learned industriousness from his father, who operated three delicatessens. At the age of 13 Boesky bought a 1937 Chevy truck, painted it white and sold ice cream from it at Detroit’s parks, making about $150 a week in nickels and dimes.

A three-time college dropout, Boesky entered the Detroit College of Law in 1959, which then did not require an undergraduate degree for admission. He withdrew twice before receiving his degree five years later.

While in law school Boesky married Seema Silberstein, the daughter of Ben Silberstein, a real estate developer and the owner of the Beverly Hills Hotel.

Unable to find employment with any major Detroit law firm, Boesky moved in 1966 with his wife and the first of their four children to New York, where he floated from job to job on Wall Street.