The bestselling PC game of the 20th century wasn’t made by Activision, Blizzard, or Electronic Arts. It was built by seven people working out of their homes in the rolling hills near Spokane, Washington — a town so far east of Seattle, it’s almost in Idaho.

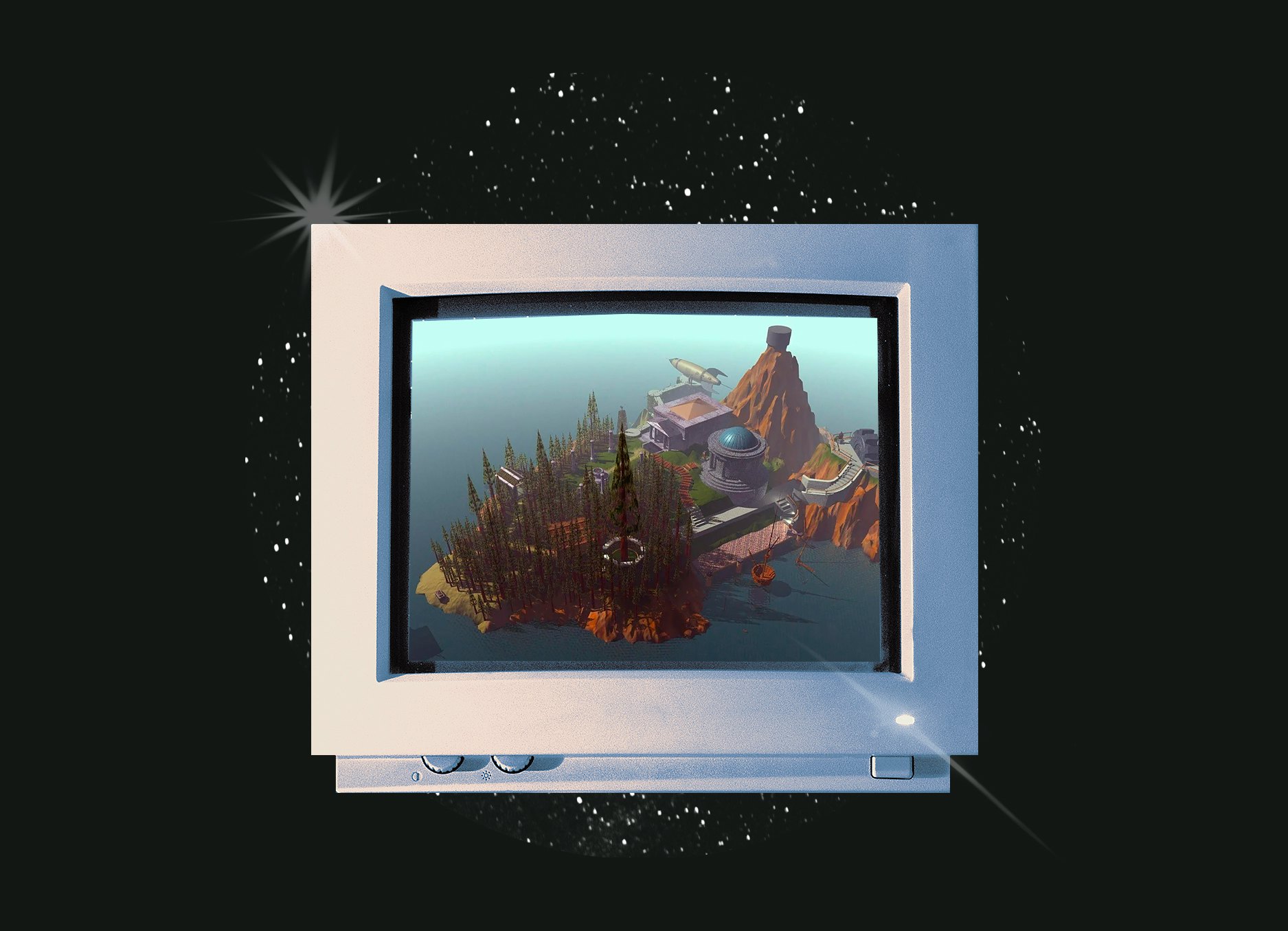

In the mid-’90s, more than 6 million cardboard boxes and jewel cases of Myst flew off shelves faster than retailers could restock them, and a tiny indie studio called Cyan, Inc. (now Cyan Worlds) became the first garage band to go multiplatinum in the punk-rock days of CD-ROM.

“Even when Myst started being really successful, I didn’t believe it,” Cyan co-founder Robyn Miller tells Inverse. “People were writing articles for big magazines and coming to take photos of us, but it wasn’t until much later that it sank in for me.”

A long-awaited sequel, 1997’s Riven, was heralded as a visual and narrative masterpiece in its own right. But in the 2000s, Cyan made a bold investment in the future of gaming that backfired, forcing the CEO to lay off all but two of its 40-person staff. After nearly a decade with no major releases, a 2013 Kickstarter campaign revived the studio. Now, it’s making award-winning games again in an industry dominated by corporate behemoths and buyouts.

As we celebrate the 30th anniversary of Myst this year, Inverse presents an oral history of Cyan Worlds according to the visionaries who made Myst, Riven, Uru, and Obduction — as well as new glimpses at some of their forthcoming games.

Out of the manhole, into the Myst

Like Myst itself, the story of Cyan begins with two brothers. In 1987, when Rand Miller asked his younger brother Robyn to illustrate an interactive storybook, they formed a two-person company called Cyan, inspired by the open-endedness of a bright blue sky. Over the next three years, Cyan made some of the first-ever children’s games on CD-ROM: The Manhole, Cosmic Osmo, and Spelunx, all critically acclaimed. But in 1991, a surprise $250,000 investment from a Japanese developer changed everything.

Robyn Miller (co-founder): We wanted to do something for adults, but we felt like it was never going to happen. Then Sunsoft came to us out of the blue. They had been funding the conversion of The Manhole in Japan.

Rand Miller (co-founder): We weren't going to have a meeting in our homes, so we rented a hotel space and served coffee. We were super nervous. The one question they had for us was, “Is it going to be better than The 7th Guest?” And we were like, “Oh yeah, it's going to be better.”

Robyn Miller: I was really into Jules Verne at the time, and I was reading The Mysterious Island, so there are a lot of similar themes. The name Myst definitely came from that book.

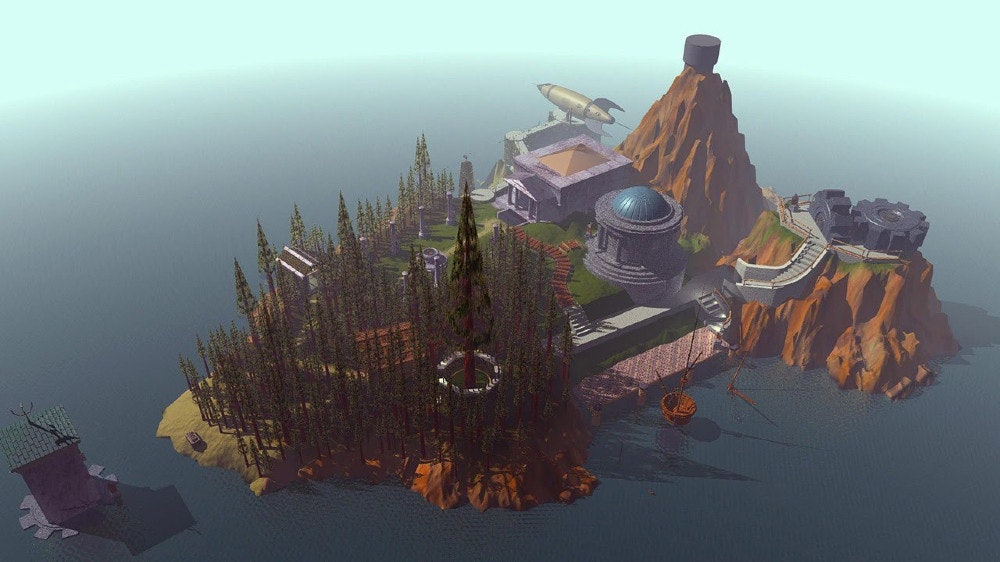

Rand Miller: Memory was small. We knew we'd have to load in different pieces [via HyperCard], so we immediately went to islands.

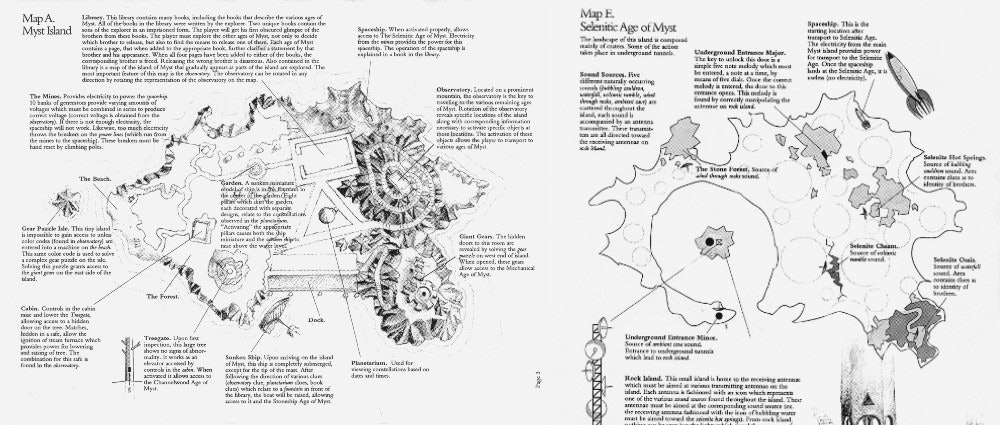

Robyn Miller: When I first sat down to create the visuals, I was drawing something more like The Adventures of Tintin, with a ligne claire aesthetic. And then I got out the StrataVision [3D] to see if it could create an entire island — knowing that it was impossible. It wasn’t designed to do that. So when I tested the landscape and was able to do a grayscale extrusion? It was thrilling.

Robyn Miller: I had been working on a novel. My passion was writing. I never meant to make video games. But at some point in time, we decided Myst needed more of a story, so we got out that book of mine and that's where the underground kingdom of D’ni came from, and some of the characters, and fire marbles.

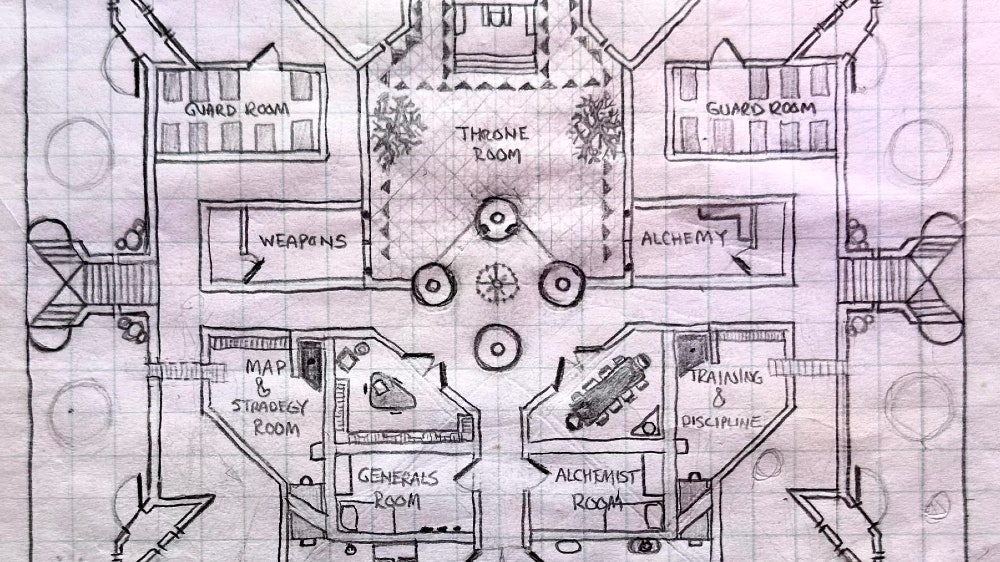

Rand Miller: We had a brother who was into Dungeons & Dragons, and after I played a couple times, I was like, “I don't want to play it, I want to take people through my own world.” So I drew a whole series of images and designed this whole fortress. The Mechanical Age was loosely based on that fortress.

Robyn Miller: We moved these big wireframe models around and pressed render, and then we waited three hours, four hours, six hours. And when we came back, it really felt like we were getting a glimpse into another world.

Robyn Miller: Even when Myst started being really successful, I didn’t believe it. People were writing articles for big magazines and coming to take photos of us, but it wasn’t until much later that it sank in for me. After millions of copies of Myst had been sold, I walked into this sports stadium with Rand and a producer, and I said, “This many people have played Myst.” I couldn't process it.

Riven by pressure

If Myst was their version of The Hobbit, Cyan wanted to make a sequel on the far more epic scale of The Lord of the Rings. A new co-director named Richard Vander Wende — the production designer of Disney’s Aladdin — pushed the Millers to abandon the surreal aesthetic of Myst and replace it with character-driven photorealism. But creating more than 4,000 images and live-action videos across five separate CD-ROMs turned out to be more difficult than they ever could have imagined.

Rand Miller: We had lots of Myst resources, so we just put that money into Riven. There was a ton of pressure, but I have a certain amount of — well, if you’re gracious you’d call it naïveté, and if you're not so gracious, you’d call it stupidity.

Robyn Miller: I tried not to listen to the pressure that was coming from Brøderbund. I know it caused friction within [Cyan] to just focus on what kind of game I’d like to play, and what kind of world I’d want to be in.

“To me, it wasn't a game. It became a real place in my mind.”

Richard Vander Wende (co-director of Riven): Aladdin almost killed me. I was working 120 hours a week on it by the end and not getting enough sleep. I was so thoroughly burned out that I left Disney, and I had no idea what I was going to do next.

But some friends had tickets to this computer convention in Los Angeles, and I was about to leave when I noticed Robyn Miller standing about 10 feet back from people playing Myst. We started chatting, and I had a three-hour lunch with [Robyn and Rand] at the Bonaventure Hotel.

Rand Miller: Robyn and I were approaching Riven the same way as Myst. We were evolving slowly and trying to do things more coherently, but Richard expedited that and enhanced it.

Richard Vander Wende: Robyn said, “For the next one we’re going to buy Silicon Graphics [Indigo] workstations.” They were $35,000 each, and the [Softimage 3D] software licenses were $30,000 each.

They said, “Do you think you're going to be able to do this?” And frankly, I had no idea.

Richard Vander Wende: Riven was supposed to take two-and-a-half years and ended up taking three-and-a-half years. I staunchly refused to work weekends, and Robyn and I had a big fight about that. We all went a little crazy. It got tense toward the end.

Rand Miller: We spent a few weeks in the Bay Area filming the live-action stuff for Riven. And I kid you not, it was the 70th take of the final scene, and I was like, “What am I doing? 70 takes?” Richard was directing, and he's a perfectionist, so some of those takes were just trying to get blood from a stone with me.

Richard Vander Wende: To me, it wasn't a game. It became a real place in my mind.

Robyn Miller: We went back and forth and argued about the name. I was on the side that said, “We're going to name this thing Riven, and we’re not even going to put Myst on the box!” And Rand was on the side that said, “No, this is Myst II, we need to put Myst on the box.” In hindsight, I think Rand was right. A lot of people went into stores who wanted to buy the next Myst, and they never saw it.

Richard Vander Wende: [VFX pioneer] Douglas Trumbull flew out for a visit and we showed him the game. At the end, the lights came back up and he was flabbergasted. He turned to us and said, “Nobody in Hollywood is doing stuff this good.”

Robyn and Rand didn't have to put as much money into Riven as they did. But they had this belief that what they were doing transcended worldly concerns.

Robyn Miller: Surprisingly, it was not a difficult decision to leave [Cyan] after Riven. At the time, it was surprisingly easy.

Richard Vander Wende: I needed some time to recoup. I didn't know if [Riven] meant anything to anyone. The first thing I heard was my new next-door neighbors. When my wife mentioned Myst and Riven, the husband — who worked at Microsoft — said, “Oh, they’ve really lost it. It’s not what Myst was.” And the family members I sent copies of the game to… it was just too difficult for them to get through. So I thought, Did we fail? I just didn't know.

Rand Miller: It was a really big moment when Robyn and Richard left. But like any band, sometimes you've got things you want to try on your own. I know Robyn felt that way. He's a storyteller, and having control of the story is hard to do in games. But I loved the undiscovered country of that.

The cavern and the cave-in

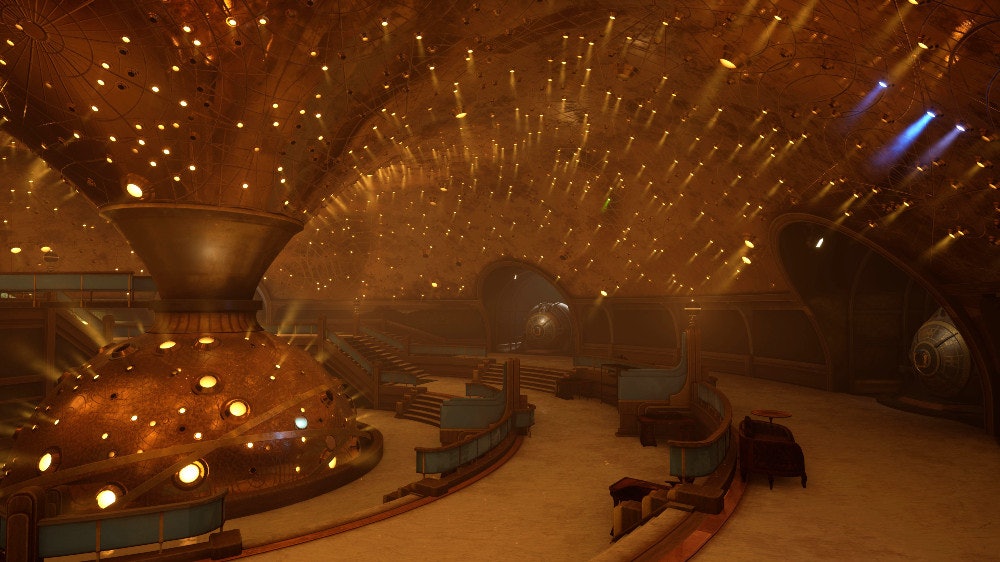

After licensing the rights for Myst III and Myst IV to another studio, Cyan began staffing up for Uru, an ambitious online RPG with real-time 3D environments set in the underground city of D’ni and other worlds. But the fate of Uru — and of Cyan itself — may have been sealed the day they signed a deal with Ubisoft.

Rand Miller: After Riven, I wanted to explore worlds and stories that were more alive, that felt like they could change every night. And that became Myst Online, or Uru.

Eric A. Anderson (creative director): Cyan was stupid enough to offer me a job, and I moved to Spokane in the summer of 2000. It was magical.

Most of the Riven crew had dispersed, so it was a new crew of people in this dark basement with basalt pillars and Riven daggers just stabbed willy-nilly into the top of these giant wooden desks. And then it got even crazier because we built that second building and started beefing up the team rapidly.

Rand Miller: Did I mention I'm kind of naïve? It didn't seem risky to me. It seemed like a no-brainer. Both Microsoft and Ubisoft wanted Uru, but both of them were hesitant to fund it — even though we’d already done all the work and put all the money into it ourselves.

Eric A. Anderson: We look at Uru now and it’s a little dated, but you have to understand that in 2000 it was mind-bogglingly amazing. The level of graphical fidelity and the worldbuilding acumen was off the charts.

Rand Miller: When we decided to go with Ubisoft, I sat across the table from them and said, “What I really want is a commitment that you'll let this go for a year, and see what happens.” And they said, “Oh yeah, we're going to do that.” But that wasn't in writing.

Eric A. Anderson: They got cold feet. It was insane how much money Ubisoft flushed down the toilet.

Rand Miller: We had people from Ubisoft working here in Spokane who loved the project. One of them shared the news [that Ubisoft was canceling the online version of the game] and they were just — their heart was broken. Tears were shed. It was the worst possible time to pull the plug.

Rand Miller: I'm still as proud of Uru as I am of anything I've done. But it wasn't anywhere near what we were hoping to do in our original designs. It's a little sad. We were setting things up to never end. We had storylines planned out for years. We had 12 additional ages in development when the plug was pulled. I'm just going to go with, “It was ahead of its time.” That makes me feel a little better.

We managed to keep going by cutting a deal with Ubisoft for two Uru DLCs and Myst V, which was just crushing. I’m not even sure they paid us for the first DLC.

Eric A. Anderson: Our fingers were crossed, hoping that the sales of Myst V would turn us around. But it wasn't meant to be what it was. It was a Hail Mary. And then one day [Cyan] said, “Here's the situation we're in: We want everybody to look for work.”

Cyan is all about taking care of the people who work there above all else, so they gave everyone their hardware and their work computers to keep. And there was this two-week period where we thought we were done for. I was in my second round of interviews with Valve when I got a call from [Cyan] saying, “We think we pulled a rabbit out of a hat,” and that's when they sold the rights to Uru to GameTap.

An Obnormal comeback

The GameTap revival of Uru only lasted for a single year, after which Cyan entered what Anderson calls the “Dark Times” between 2008 and 2013, when a lean staff released mobile ports of their old games. Then they had an idea.

Eric A. Anderson: Double Fine was making big news for raising millions of dollars on a Kickstarter for Broken Age, and Ryan Warzecha was like, “If Double Fine can do it, Cyan should be able to.”

We started getting together every week at Rand’s house, and for a good many months we were talking about a Myst sequel. One day in 2013, Rand came in and said, “I can’t do a Myst game. There’s too much baggage. Too many rules.” So we revived an old idea called Obduction — and it revived the studio in a big way.

Hannah Gamiel (development director): When we launched the Obduction Kickstarter, we were all crowded together at like 5 a.m. in the office. It was pitch black when we pressed the “live” button, and seeing the pledges roll in was really exciting.

Rand Miller: Kickstarter was really amazing for the excitement level, both inside and outside the company, but it didn't get us enough money from a game creation point of view. People think a million bucks means we’ve got it made, but we had to scrape and claw our way to get Obduction done. I can't believe we did it.

Eric A. Anderson: The hardest thing about Obduction was also the best thing about Obduction, which is that we were too naïve and too stupid to realize how big of an undertaking we were signing ourselves up for. I can't believe we made it.

Hannah Gamiel: At the very end of the project, when we shipped Obduction, I remember this massive feeling of relief.

Under a new Firmament

In 2019, Cyan launched another successful Kickstarter for a new science fiction adventure game called Firmament, now scheduled to release on May 18, 2023. In 2020, they released a fourth remake of Myst for modern PCs and VR, which won the App Store’s “Game of the Year” award. And in 2022, they announced a long-anticipated remake of Riven — and brought Richard Vander Wende back to help reimagine it.

Eric A. Anderson: When they ran the Firmament Kickstarter, Hannah [Gamiel] and I were working for Jonathan Blow at Thekla. We both lived in Spokane and we were playing with the idea of doing our own game. She's a programmer, I'm an artist. But after the Kickstarter campaign was over, I got a text from Rand.

Hannah Gamiel: Rand and Tony [Fryman, president of Cyan] called me to meet up at a Starbucks nearby, so I walked in with a notepad and a pen, and I remember Tony laughing at me and saying, “Girl, you're going to be writing a lot at this one.”

“If any stories needed to be kept secret in our history, this is the one.”

Eric A. Anderson: They said, “We want to retire someday, and there's only two people we would trust Cyan with: You and Hannah.” And If I could travel back in time to tell myself in 1997 — who is starry-eyed playing Riven for the first time — that there would come a day when Atrus would ask me to take the reins [of Cyan], I would have punched myself in the face, because that's impossible.

Hannah Gamiel: We called Jonathan [Blow] and we were honestly terrified to tell him. But he was so kind.

Eric A. Anderson: He said, “I get it. It's not every day somebody takes a successful game studio and hands it to you. You have to do this.” So in 2019, we both quit [Thekla], and came back to Cyan.

Hannah Gamiel: Eric handles a lot of the creative decisions like Rand, whereas I'm more of a company steward like Tony. And I feel like it's important to clarify that I’m Rand’s stepdaughter, because that whole time I had imposter syndrome. I wondered if people would see me as getting this job because I earned it or because I'm related to Rand. But over the years, my co-workers have been so nice [and] shown me that the ability to do the job is the most important thing.

Rand Miller: Firmament is exciting because we've got VR in mind, and it's a story we all got really excited about. If any stories needed to be kept secret in our history, this is the one. We're approaching it a different way. The gameplay mechanisms are different. The way we tell the narrative is a little different. The UI is different. Even the way we designed it is different.

Hannah Gamiel: The Kickstarter didn’t cover the full amount we needed to create the game in a year. But I said, “You know what we could make in a year?” I'm sure every Myst fan in the world would have rolled their eyes, but no one’s ever been able to play Myst in VR before. And that was probably the best decision we could have made, because it helped us hire 10 more people to work on Firmament.

Eric A. Anderson: If you thought Obduction was a weird game, you ain't seen nothing yet. I'm excited… and I never want to make a game this large again in my life.

Hannah Gamiel: To people who are fans of our games, I would say: get ready to exercise a slightly different part of your mind.

Rand Miller: After Firmament, the biggest thing we’re working on is the remake of Riven.

Richard Vander Wende: We're not making a carbon copy of the original [Riven], because that’s its own thing. When Rand first brought me on, he asked, “What would you do differently this time? What would you like to do that we couldn’t the first time?”

Hannah Gamiel: There may very well be places you’re able to go now that you couldn’t before...

Rand Miller: We want to see if we can tell the story better. To us, Riven is a real place… and now we’re giving people more glimpses into that place.

After that, a new Myst game looks like a good possibility, but planning out that far ahead is hard. The Myst TV series is on the back burner, just because of the nature of streaming right now. [The chances of finishing The Book of Marrim] went up a little last year, and then back down a little this year.

Hannah Gamiel: We very much intend to re-release the first three Myst novels in a physical format this year. Rand’s making some updates to the books that I think people will love.

Eric A. Anderson: We're hoping to diversify a bit, and not necessarily just do these giant games that take forever. Our subgenre is very risky, so we're having conversations about what we can do with the strengths of Cyan that gives us a little more freedom and stability.

Hannah Gamiel: Making single-player puzzle adventure games that take two to four years is not the most profitable venture in the world. We’re going to focus on smaller beats, and maybe even explore other genres.

Eric A. Anderson: It's been the best, but also the hardest three years of my life. Turns out, it's very difficult to run a company ethically, take care of people, and make hard decisions.

Hannah Gamiel: People genuinely care about each other here. That’s the undying soul of Cyan. That’s the oil that keeps burning.

Rand Miller: One of the things I told Hannah and Eric is, “We never say business is business.” That's crap. That's not how this works. Business is people, and it always has been.