Title IX radically altered the sports landscape, but not all at once and not without resistance. In the early years of the statute, the “forgotten heroes” challenged bias and championed equality—and the impact is still felt today. Read more about Title IX’s pioneers to remember here.

When Florida sophomore Talitha Diggs dashed across the finish line in 50.98 seconds on March 12 at the NCAA Indoor Track and Field Championships in Birmingham, she didn’t simply win the 400-meter title. She captured a piece of history.

Thirty-nine years earlier, her mother, Joetta Clark, took home the NCAA indoor crown in the 800 meters, her first of nine overall titles during her storied career at Tennessee in the 1980s. With the 19-year-old sprinter’s indoor title, the pair became the first mother and daughter to both win an NCAA championship in an individual event—a feat that squarely represents the wave of athletic opportunities that began to be afforded to women only after the passage of Title IX in ’72.

Walter Iooss Jr./Sports Illustrated

Running became a family affair thanks to Joe Louis Clark, Joetta’s father, the no-nonsense, inner-city New Jersey high school principal who was famously portrayed by Morgan Freeman in the 1989 movie Lean on Me. His tough love and unorthodox disciplinary measures helped turn around one of the state’s most troubled schools, and he took the same approach with his three children, particularly on the track. Clark pushed 12-year-old Joetta into distance running, not sprinting, because he sought to prove that Black people could succeed in longer races, too.

Armed with her father’s tenacious spirit, Clark never lost an 800-meter race during her four years at Columbia High School in Maplewood, N.J., from 1976 to ’80; in fact, to this day, she holds the state’s outdoor record in the event. During her four years as a Vol, she was a 15-time All-American, a nine-time national champion and 10-time SEC champion. It wasn’t until she arrived on campus that she realized the impact of Title IX. It was the first time she saw women in sports leadership roles.

“My track and field coach was Terry Crawford, Pat Summitt was doing basketball, Gloria Ray was the athletic director and Debby Jennings was the [sports information director],” Clark says. “It was inspiring to see all of these women in charge and winning.”

Andy Lyons/Getty Images

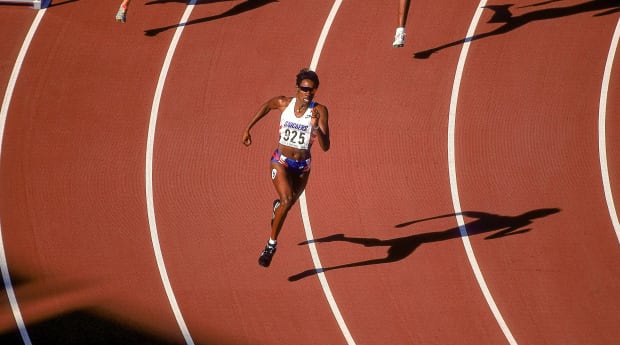

After college, she became a four-time Olympian, running at the pro level for more than 28 consecutive years. By the time Clark entered in her final Olympics in Sydney 2000, her half sister, Hazel, 15 years her junior, was making headlines of her own in the half-mile distance and competing in her first Summer Games. By then, the path had already been paved. Hazel never had to fight for the amenities she enjoyed: the expensive equipment, the nice facilities, the chartered flights, the prestigious meets and more.

“To her, it was always like this. She didn’t take it for granted, but it just didn’t register,” Clark says. “They think they’ve arrived. But my generation, we were far from arriving. So we had to press forward—as women, as Black women, as women running distance.”

Now 59, Clark says it was the groundwork set by the women at Tennessee that inspired her current career as a motivational speaker and founder of the Joetta Clark Diggs Sports Foundation, which promotes participation in athletics.

In June in Eugene, Ore., Talitha made history once more—this time at the NCAA Outdoor Track and Field Championships, where she captured the 400-meter title.

Just as she did with her sister, Clark reminds Talitha of the sacrifices that came before her, of the women who paved the way.

“What I do now is very focused on what I saw then,” she says.