President Donald Trump has spent his first weeks in office calling for the U.S. to buy Greenland while refusing to rule out the possibility of military force — even as officials declare the country isn’t for sale.

Trump claims the U.S. needs to own Greenland in order to address national security concerns — and it’s not the first time the country’s strategic importance has been the focus of the U.S. military.

More than six decades ago, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers was hard at work on a project in Greenland: Camp Century.

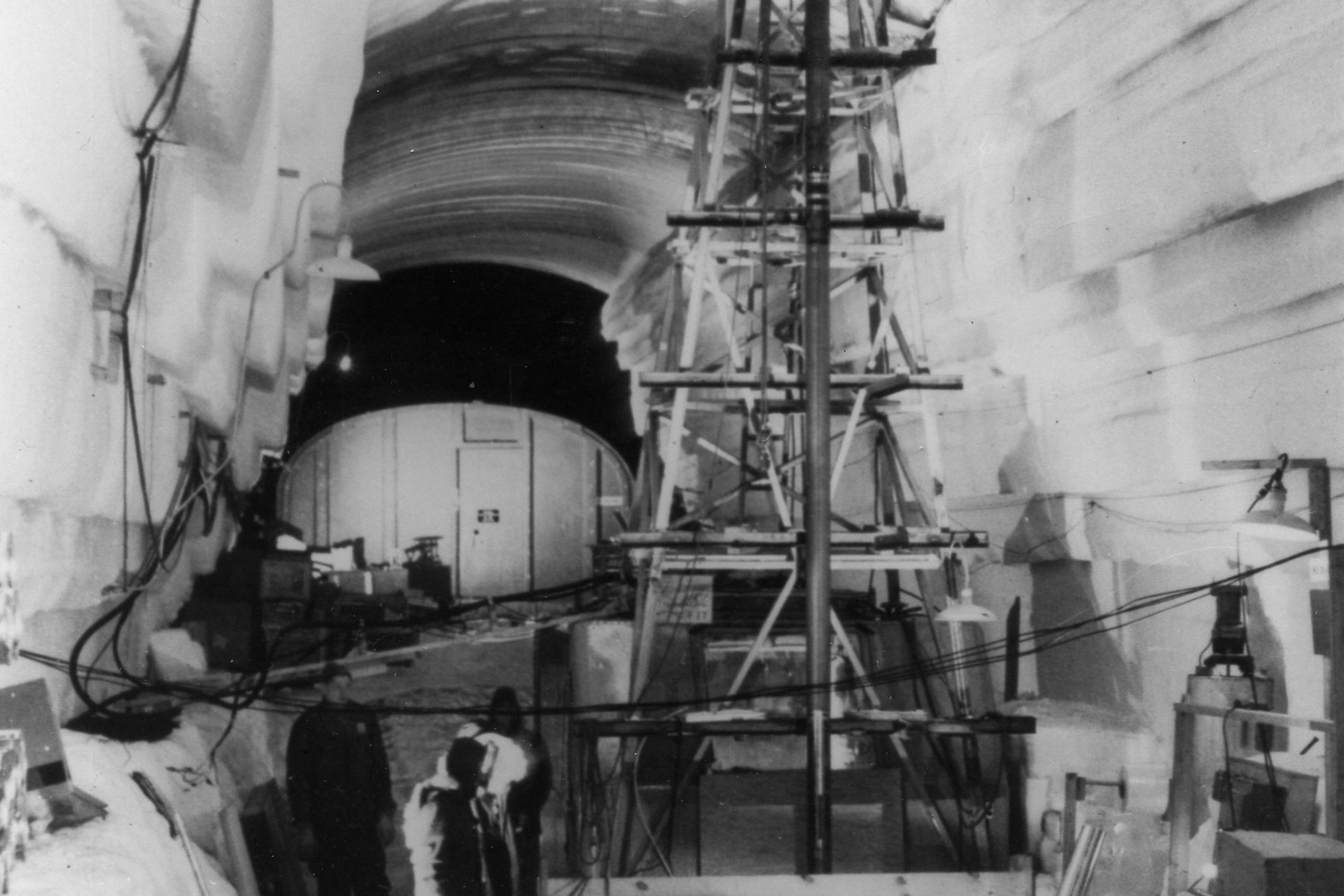

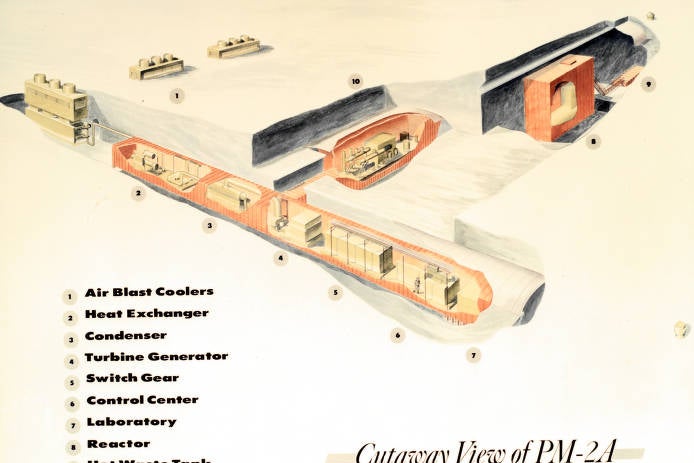

The project itself, set in a military base with two miles of tunnels, wasn’t entirely classified. Journalists were invited to visit the area, and the army advertised it as a nuclear power base, National Geographic reports.

But hardly anyone knew the truth: Camp Century was also developing Project Iceworm, a network of complex tunnels and railway tracks that could house and transport some 600 nuclear missiles. These missiles could then be shot over the north pole toward the Soviet Union.

Now, new information on the mysterious base has come to light.

Why Camp Century was built — and why it was abandoned

Camp Century was built in 1959 and was operational for seven years. The crew lived in extreme isolation, 127 miles away from other people, according to National Geographic.

The only way to reach the base was via sled — and heavy snow, wind or freezing temperatures could make the journey difficult. But Austin Kovacs, an army research engineer who worked at Camp Century, said it never felt dangerous.

“People thought it was dangerous,” he told National Geographic. “And it was not dangerous. It was comfortable. And at times it was very, very monotonous.”

The base wasn’t just equipped with research facilities — it also included a clinic, a theater and a library, NPR reports.

“We had everything you could imagine — lights, and heat, and all that kind of stuff,” John Fresh, a soldier who visited Camp Century, told NPR. “It was cold. I mean, you know, when you walk down there, you could feel it’s like walking into a freezer.”

As for Project Iceworm, few were in the know — until years later. It was only in 1968, when a U.S. jet armed with nuclear bombs crashed, that an investigation into American activity in Greenland was launched, NPR reports. The investigation revealed that the Danish prime minister had covertly approved Project Iceworm.

However, while they did a good job keeping the secret, army planners hugely miscalculated the reality of building a base inside a glacier. The unpredictable nature of glaciers meant that steel railways could buckle because of the movement, and missiles might tip over. Even the atomic reactor itself was at risk as the ice below it shifted, National Geographic reports.

Eventually, army officials admitted this might not be the best idea, and the nuclear reactor was shut down in 1963. By 1967, the camp had been completely abandoned.

By 1969, the camp was in ruins, National Geographic reports, with snow spilling into hallways and splintered wood beams.

Modern-day insights into Camp Century

Researchers are still trying to piece together everything that happened at the mysterious Greenland camp.

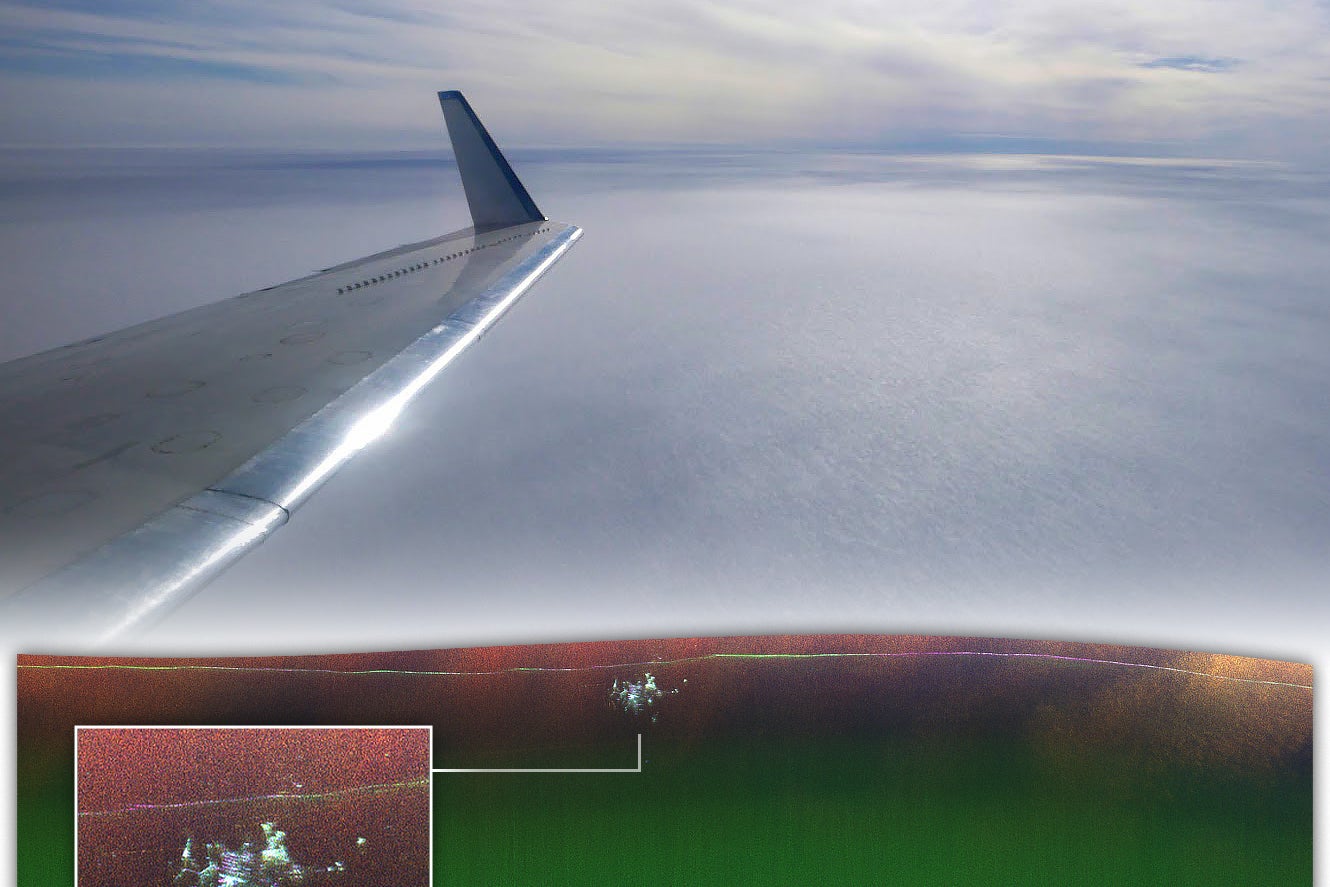

Last April, Nasa scientist Chad Greene and his crew were flying over Greenland when their radar unexpectedly picked up Century’s vast network of tunnels underneath the ice.

“We were looking for the bed of the ice and out pops Camp Century,” Alex Gardner, a cryospheric scientist at Nasa’s jet propulsion laboratory, said in a statement. “We didn’t know what it was at first.”

Their readings helped map the vast buildings and hallways of Camp Century better than ever before. Now, after snow and ice have continued to accumulate, the base is some 100ft under the surface.

“In the new data, individual structures in the secret city are visible in a way that they’ve never been seen before,” Greene said.