The Paris Olympics will host a countless number of fast runners. But perhaps the ones with the most potential for speedy, record-breaking times are going the farthest. It’s no secret that marathon times over the past decade have dropped significantly. And while we have novel science-informed training techniques as well as more professional year-round runners dedicating their lives to the sport to thank, we also have technology. So-called supershoes have transformed distance running in the past eight years and are with little doubt playing a role to bring marathon times down in both the women’s and men’s races and in elite and novice times.

Just look back seven months ago, at the 2023 Chicago Marathon, where the late Kelvin Kiptum, a 23-year-old runner from Kenya, ran 26.2 miles in a world record of 2 hours and 35 seconds. Kiptum beat out the marathoning legend Eliud Kipchoge’s official world record, set more than a year prior, by a full 30 seconds. While Kiptum, who died in a car crash this past February, received credit as an up-and-coming force for distance running, there was just as much discussion about his shoes.

To achieve his record-breaking feat, Kiptum was sporting a then-prototype version of Nike’s Alphafly 3, the latest rendition of the company’s cutting-edge marathon shoe meant to enable distance runners to propel themselves faster with more ease than any footwear that came before it. If you aren’t in the running world, the shoes appear odd. They have a 40-millimeter thick midsole — chunky enough to rival any fashionable platform sandal, and importantly, legal within the World Athletics regulations of 40 millimeters or less — and they sport a pair of literal air pods (yes, pockets of air) studded across the sneaker’s forefront.

The Alphafly 3 is the current culmination of years of innovation by Nike, which began with the breakout 2017 release of the Vaporfly 4%, the first marathon-specific shoes with an ideal combination of carbon-fiber plate smushed inside a super-responsive foam. Since its release, shoe companies across the board have shifted gears, adding extra and better foam and that elusive plate to their distance racing shoes. Seven years later, the Alphafly 3 almost seems alien to the OG Vaporflys. Right now Nike’s got the fastest shoe in the world. What makes it tick — how it can make a fast runner faster — may offer an idea of what the future of distance running shoes hold, or just help explain why marathoners today are so darn fast.

It Was Always About the Cushioning

The impact of every step reverberates throughout the body. With each stride, the body kicks off a chain of reactions in which the bones, muscles, ligaments, and tendons must all work together to literally propel your entire body weight forward. Multiply this some 50,000-plus times for a marathon, and that’s a lot of impact. This is why shoes are such an essential tool for distance running — and why cushioning has long been the center of technological innovation.

Classic distance running shoes of the past several decades include the New Balance Trackster and the Onitsuka Tiger Marathon, of the ’60s and early ’70s, to name a couple. While these shoes were lightweight, pliable, and somewhat comfortable, their midsole cushioning was nearly non-existent (though far better than what came before, which were essentially Keds-like shoes made out of leather). And almost no runner today would consider running 26.2 miles in them.

It wasn’t until the 1970s when ethylene vinyl acetate (EVA), a rubberlike foam known for its softness and flexibility, was introduced to running shoe midsoles. To this day, EVA is found in everything from kids toys to medical equipment, and it’s become a staple to the running shoe midsole, though other, newer foams have come along.

From the 1970 to the early ’90s, there was frankly not all that much innovation in running shoes. There were attempts to make shoes thicker — like the Nike Air Max, et cetera — but they also made them heavier and chunkier in a way that didn’t give back. This may have helped fuel the push towards minimalism in the earlier 2000s. But even the minimalism days of the early 2000s, fueled by Chris McDougall’s Born to Run and Vibram FiveFingers’ subsequent record-breaking sales, didn’t last long. The entire premise of the minimalist shoes and movement was that they’d reduce injuries by allowing us to use our feet and bodies more naturally. But the entire movement came to a crashing end with a 2012 lawsuit against Vibram for false advertising that its shoes would make runners injuryproof. To this day, it’s hard to quantify precisely what leads to a running injury.

By 2017, running shoe companies like Altra and Hoka One One were already experimenting with the idea of a clunky, maximalist midsole. But Nike took it one step further by adding polyether block amide (also known as PEBA or PEBAX, if it is sourced from producer Arkema), which is essentially the bounciest foam yet put in a shoe — alongside a controversial carbon fiber plate. The end result was the Vaporfly 4%, so-called because Nike claimed the shoe could improve running economy in anyone wearing the shoes by as much as 4 percent.

The Effect Is Greater Than the Sum of Its Parts

To say that the Vaporfly shook the running shoe industry would be an understatement. Marathon times got better — from the elite to the novice and everything in between — the data does not lie. As The New York Times put it, “there is no such thing as a large-scale randomized control trial for marathons and shoes.” But in the early years following the release of the Vaporfly 4% and Next%, the Times used data from the fitness app Strava to analyze race times by runners using the platform — including their self-reported footwear — and found that a runner wearing either the Vaporfly 4% or the Vaporfly Next% ran 4 to 5 percent faster than a runner wearing what they called an average shoe. These runners also ran 2 to 3 percent faster than runners in the next-fastest shoe on the market. In fact, at the end of 2019, about 41 percent of marathons run in less than three hours had been run in one of these two Nike shoes.

On the professional level, both the current marathon records on the women’s and men’s side were run in supershoes, either Nikes or another shoe company’s iteration of a carbon plate plus ultra-responsive midsole.

“The Vaporfly … opened that door to a new way of thinking,” says Elliott Heath, a running footwear product manager at Nike who oversees the racing portfolio across track, field, and road models. Prior to his role in Nike footwear, Heath was an all-American collegiate middle-distance runner and ran professionally for the brand. He currently coaches at the Bowerman Track Club, one of Nike’s elite running clubs.

“Before the Vaporfly launched … the word for racing shoes was racing flats and that was the idea — that you keep taking material away and basically provide a minimal amount of cushioning for the athletes and make a lightweight shoe and that was the best marathon racing shoe. The Vaporfly completely changed that paradigm and way of thinking.”

Since 2017, other running shoe companies have had to play catch up, adding better foam (often PEBA-based) and carbon plates into their shoes, and bringing down the weight as best as scientifically possible. For Nike specifically, the company has, year-after-year, refined their elite racing shoe evolving from the original Vaporfly 4% to the Next% to the Alphafly.

Its current shoe, the Alphafly 3, is the culmination of years of refinement. It’s also now not the only so-called super shoe on the market. Just about every major footwear company that caters to distance runners, including the professionals they pay that race in their shoes, has its own version, including Puma’s Deviate Nitro Elite 3, New Balance’s FuelCell SuperComp Elite v4, and Asics’ Metaspeed Edge 3.

The Paris Olympics will display a host of these shoes that are all, on a general level, trying to live up to the Alphafly 3, still argued to be the fastest marathon shoe in the world.

What Makes The Alphafly 3 So Fast

1. THE FOAM

An unfortunate truth about any shoe, running or otherwise, is that it never returns as much energy as you put into it. With each stride, a runner puts a certain amount of energy into the shoe. The more responsive the foam, the more energy that shoe is able to give back to the runner with each step.

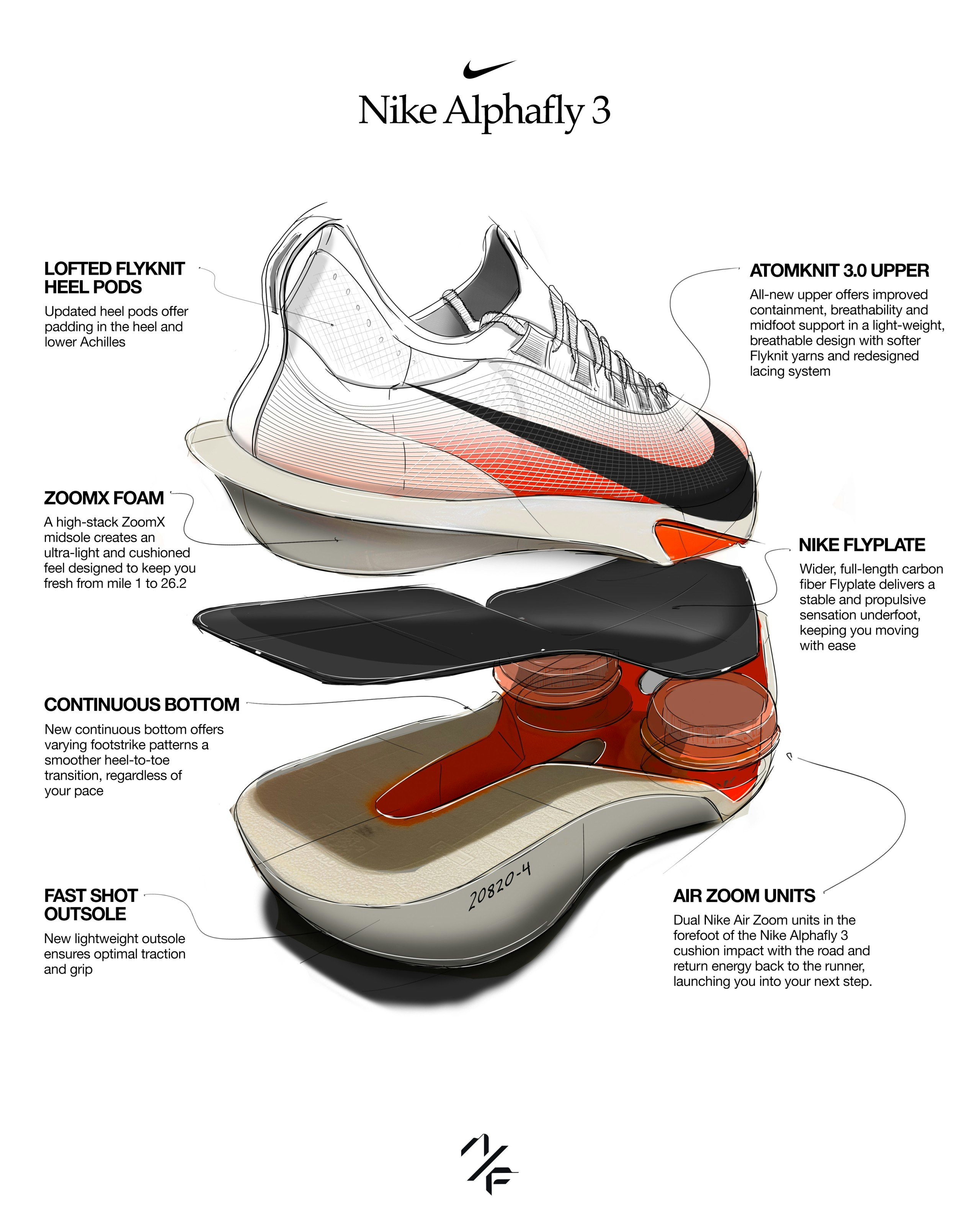

How much energy any one type of shoe returns, whether it’s the Alphafly or a pair of sandals, is incredibly hard to quantify, as it changes depending on how a person walks in and uses the shoe. But various biomechanical testing can give estimates. One oft-cited 2018 study in the Journal of Sports Medicine that measured and compared the energy return of the three main types of midsole foam used in running shoes — EVA, TPU, and PEBA — found that EVA foam returned about 66 percent energy, whereas TPU returned as much as 76 percent, and PEBA, which is what the Alphafly 3 contains and what Nike calls “ZoomX”, generated 87 percent energy return back to the runner.

ZoomX foam has been in Nike’s line up of shoes since 2017, but it's added an extra layer of cushioning into its Alphafly 3’s. “What we’ve learned from that launch of the [original Vaporfly shoe] is what the components are that are most important for the marathon,” says Heath. “That extra amount of foam underneath the foot allows for more energy return.” The Alphafly 3 has an even larger midsole than any of its predecessors, Heath says.

Nike declined to say how much energy return its Alphafly 3 shoes provide, but said its inhouse testing of its shoes against its rivals revealed the Alphafly 3 had a superior energy return.

2. THE CARBON PLATE

Foam can only get you so far, though. Even the bounciest shoes are going to be just that — hyper bouncy. In 2017, when the original Vaporfly 4% shoe came out, it contained a carbon fiber plate, which was an immediate game changer.

While carbon fiber plates have been in running shoes — from track spikes to a failed introduction to road racing shoes first by Brooks in 1989 and then a few other brands in the ‘90s — their introduction into the marathon caused an uproar: Times got faster; data, including an in-depth analysis by The New York Times, suggested that not only was the advantage these shoes provided runners wearing them real, but it was even greater than earlier studies had suggested. Quickly, it became clear that the fastest runners, and those placing highest in elite races, were wearing these carbon plate shoes. Other brands including Puma, Hoka One One, Saucony, Brooks, and On running all scrambled to squeeze a carbon fiber plate into their best midsole foam.

But what does a carbon fiber plate do? When the Vaporfly first came out, many argued that it acted as a literal springboard. As more runners and scientists got their hands on the shoes, however, it was clear that wasn’t exactly it. A pivotal 2022 study by Wouter Hoogkamer at the University of Colorado (Hoogkamer is now at the University of Massachusetts) changed everyone’s view of the carbon fiber plate. He literally sliced through the shoe and plate with a saw, making cuts throughout the plate. When runners wore the nicked-up racing shoes, their running economy got worse by less than 1 percent. “This suggests that the plate's stiffening effect on the MTP joint plays a limited role in the reported energy savings, and instead savings are likely from a combination and interaction of the foam, geometry, and plate,” the study concluded.

“I see it more as a synergy. And each one of those components amplify each other. They all have their benefits on their own but the sum of the parts doesn’t really equal the whole, where it's like you get all of those components together and all of a sudden it’s unlocked and amplified even more.”

In other words, it was less about the actual plate itself springing a runner forward or the exact energy return of the ZoomX, PEBA-infused midsole. It was the synergistic effect of the two. “The stiffness amplifies the work of the foot,” says Heath. “I see it more as a synergy. And each one of those components amplify each other. They all have their benefits on their own but the sum of the parts doesn’t really equal the whole, where it's like you get all of those components together and all of a sudden it’s unlocked and amplified even more.”

3. THE AIR PODS

The other key ingredient in the Alphafly shoe is what Nike calls Air Zoom technology, which are essentially packets of air placed in the forefront of the shoe to provide an added layer of energy return with each step. Heath says they strategically placed the air pods there as it is the last place that you engage before toeing off onto your next stride.

While Nike has put air products in their shoes for a long time, what’s different about Air Zoom technology is that they have tensile fibers that allow for higher pressure inside the air pockets while still maintaining their shape. “If you didn’t have those tensile fibers, you would essentially have something like a kickball that would expand equally in all directions,” explains Heath, making it highly unstable. The tensile fibers “enable [the shoe] to bounce back and have a high amount of energy return that is positioned in the most beneficial areas of the foot to essentially take a load and return it.”

Heath says that the introduction of the Air Zoom technology amplifies the synergistic effect seen with the carbon plate and ZoomX PEBA midsole.

Alphafly 4 — And Beyond

While Nike didn’t give specifics on what the next version of its marathon racing shoe would be, when pressed, Heath hinted that there are still many more technological advances the company plans to pursue, and some of those avenues will come from data they get from how athletes use the shoes over time. “I think there is so much left on the table to improve and some of that comes down to the footwear technology and some of it comes down to the athlete.”

Nevertheless, there’s no question these shoes are changing the game. In a few decades we will almost certainly look back at these periods as “before super shoes” and “after super shoes.” Heath agrees with this sentiment. “Athletes that were once only racing two marathons a year because of the recovery needed to come back, they are now racing three or four times a year.” We’ll see this displayed in Paris this month — Heath cites Sifan Hassan, a 31-year-old Ethiopian distance runner who runs for Nike, who is set to run an astonishing four events at this year’s Paris Olympics: the 1500, 5000, and 10,000 meter races as well as the marathon — but it's likely the best is yet to come, for athletes and for the tech.