Deep in the back offices of Iraq’s National Museum in Baghdad, at the end of a long corridor set away from the Babylonian obelisks and Assyrian winged bulls, an international treasure hunt is under way.

Wafaa Hassan is sitting at her desk, poring over a large stack of papers, sighing as she turns each page. She holds in her hands a catalogue of ancient relics that were originally discovered in Iraq, and are now scattered across the world.

“They are in the US, Britain, Switzerland, Lebanon, the UAE, Spain, everywhere,” she says. “They belong to us, and we are trying very hard to get them all back.”

Hassan is both archaeologist and detective. As the head of the museum’s recovery department, she is responsible for finding and repatriating the tens of thousands of artefacts that have been plundered from Iraq and spirited away to museums and private collections.

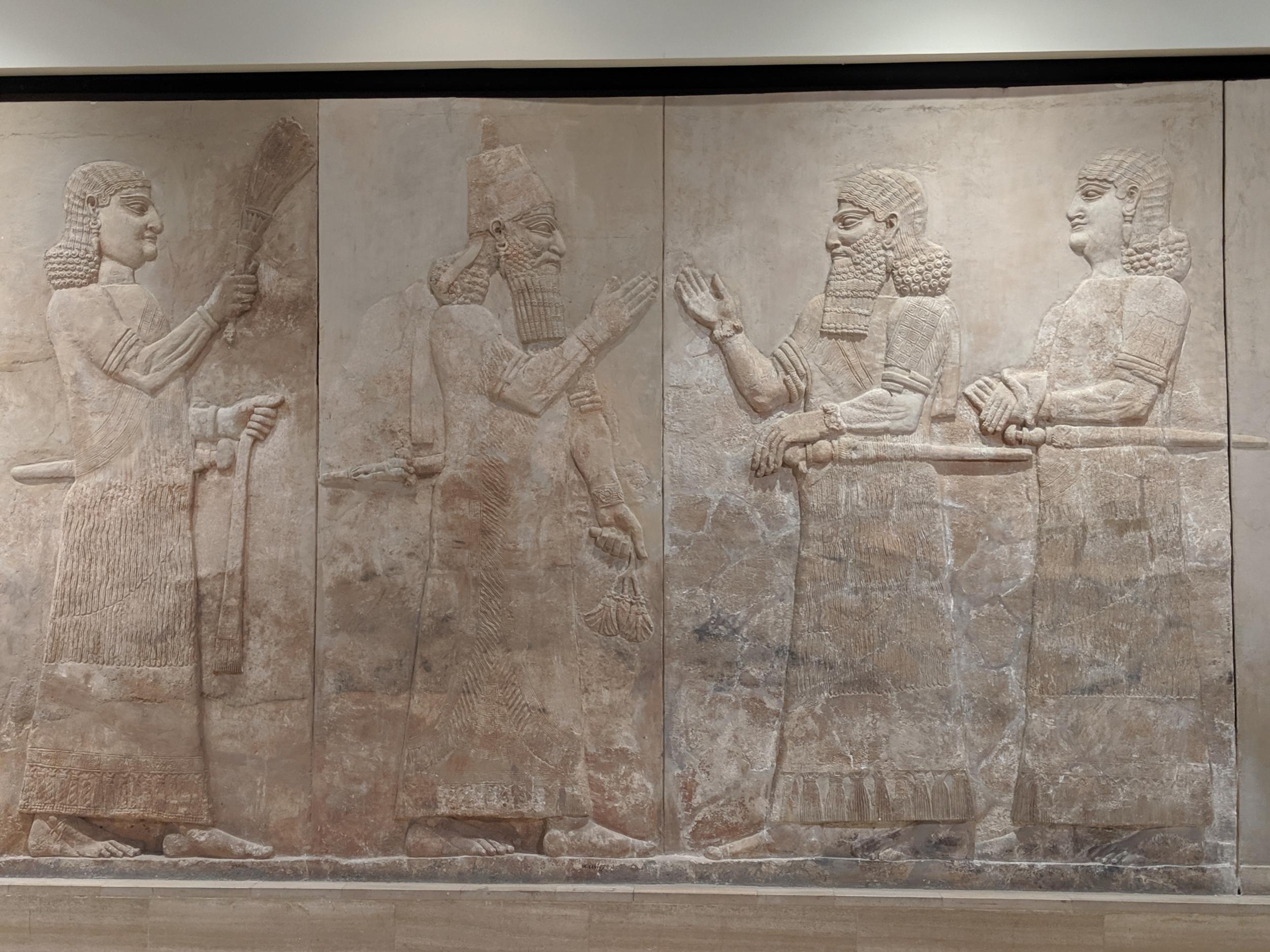

The trade and recovery of Iraq’s antiquities is a cat-and-mouse game that has been going on for decades. The country’s borders contain what is perhaps the most important archaeological region in the world. Mesopotamia, the land between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, is where civilisation was born – where the first cities were built, the first words were written and the first empires rose and fell.

But war and instability made it easy pickings for looters. European archaeologists routinely transported their finds back to their home countries during the early part of the 20th century. Illegal digging was common under former president Saddam Hussein, especially after the first Gulf War. But it was only after the US-led invasion in 2003, and the chaos it brought, that the floodgates opened.

On 10 April, 2003, after Iraqi soldiers fled and before US troops arrived to protect it, the National Museum – where Hassan works – was looted from top to bottom. More than 15,000 items were stolen – from tiny cylinder seals to the headless statue of the Sumerian king Entemena. It is considered to be one of the greatest crimes ever committed against cultural heritage.

“It made me so sad,” Hassan says of that day. “So many people got inside. It was totally destroyed.”

The museum reopened in 2015, a shadow of its former self. But even as it took its first steps to recovery, another disaster had struck. In 2014, Isis took over a third of the country – including thousands of archaeological sites and museums. The group’s strict interpretation of Islam forbids the veneration of statues and tombs. It destroyed many priceless statues and smuggled the rest to fund its reign of terror. At the height of its power, it was estimated to be making £80m a year through the sale of stolen antiquities on the black market.

Hassan’s passion for her country’s historic relics is more than equal to the extremists’ hatred for them. She strides through the museum’s halls twice a day, stopping to talk to visitors and explain each of the exhibits in as much detail as they will let her. As she sees it, every tablet and every cylinder taken from the ground in Iraq belongs in these halls.

“We are a country with a rich history, so many ancient people lived here. If you go to Babylon, the ground is full of archaeological pieces, like flowers. But so much is missing,” she says.

On the wall behind her desk is a poster with the words “Red List” in giant letters. On it are dozens of pictures of missing items that she is trying to find. Among them is a clay tablet with cuneiform writing from the ancient Sumerian city of Uruk, dated around 3500BC, and a cylinder with the name of the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal from Babylon, 7th century BC.

Hassan and her team of seven treasure hunters scour the internet for signs of Mesopotamian loot. Each item they find requires a different approach. For those held in museums in foreign capitals, diplomacy is used. Retrieving items from private collectors is a different story.

“The most important thing is the auctions,” she says. “We look at what is being sold, and when we find something, we fight very hard to get it back.”

The job puts her into contact with government agencies, police forces, Interpol, collectors, museums and embassies around the world. Government agencies are cooperative with her work, she says, and do their best to help. But she does most of the work from her office here in the museum, which limits her work.

“I cannot go to see many of these artefacts,” she says, explaining that auction houses and private collectors will often block her from inspecting items of interest.

“We have to pay lawyers in the country to go get them. Sometimes we have to leave items because we don’t have the money.”

Only around half of the items looted in 2003 have been recovered – many with the help of foreign governments and police. In March this year, the British government returned a rare Babylonian cuneiform stone that was seized at Heathrow airport during an attempt to smuggle it into the country. And it is about to return a collection of 154 cuneiform tablets that were seized in 2011.

But others are more reluctant to let them go. Different countries inevitably have different laws for the acquisition of archaeological artefacts and so there are ways for collectors to legally obtain items from ancient Mesopotamia, which makes it difficult to get them back.

“Sometimes people will say: ‘It belongs to me!’ There are laws in these countries that grant them ownership. It makes me crazy. They must know that these things are stolen,” Hassan says.

Among all the papers on Hassan’s desk, one folder towers above the rest. It’s a dossier on one of a major collector of Mesopotamian antiquities, the multi-millionaire Norwegian businessman Martin Schoyen.

On Wednesday, two items from his collection were sold at auction at Christie’s in London. One is a 5,000-year-old Mesopotamian clay tablet with proto-cuneiform writing – carved images to denote monthly rations. It is, according to the lot description, “the earliest known recorded writing system by man”. It was sold for £62,500. The other is a Babylonian tablet from around 1812BC listing centuries of Babylonian kings, which went for £18,750.

“This is a new case in my department,” Hassan says of the tablets. But Schoyen is well known to Hassan, as is his collection.

Schoyen has been at the centre of a years-long controversy over his possession of 654 Aramaic incantation bowls, which were imported into the UK in the 1990s. The case is an example of the intricacies and difficulties of Hassan’s work.

According to an investigation by Science magazine, a peer-reviewed academic journal, Schoyen acquired 444 of the bowls from a London-based antiquities dealer named Chris Martin, at least 300 of which came from a Jordanian dealer named Ghassan Rihani. The article says Schoyen then began acquiring the bowls directly from Rihani.

The Schoyen Collection later lent the bowls to University College London to study. But when a Norwegian documentary on the collection questioned their provenance, the university set up a commission of inquiry to discover the source.

The result of the inquiry was never published. Schoyen launched legal action against UCL to have the bowls returned to him. He won and UCL paid an undisclosed sum of compensation. It later released a statement announcing that “no claims adverse to the Schoyen Collection’s right and title have been made or intimated”.

UCL did not publish the report at the time, reportedly as part of that settlement. But the findings were made public by Professor Colin Renfrew, an archaeologist at the University of Cambridge, who was among the panel of experts that compiled it. Renfrew told the House of Lords, of which he is a member, that the inquiry found “on the balance of probabilities that the bowls were removed from Iraq, and that their removal took place after 6 August 1990’, and was therefore illegal”.

According to a review of the report in Science, the experts cited a law in Iraq dating back to 1936 which prohibits the export of antiquities except for exhibitions and research. It did not question Schoyen’s legitimate title to the bowls, and found “no direct evidence that positively contradicts or impugns Schoyen’s honesty”. Nonetheless, it recommended “the return of the incantation bowls to the Department of Antiquities of the State of Iraq”.

The Schoyen Collection denies the findings of the report as revealed by Renfrew. A spokesperson for the organisation told The Independent: “Following a searching investigation by experts and enquiries by UCL into the provenance of the incantation bowls, the latter confirmed publicly that it had no basis for concluding that title is vested other than in the Schoyen Collection.

“Any assertion that the Schoyen Collection might be looted or smuggled is incorrect. The bowls were part of an established collection that was put together over many years by generations of collectors in Jordan, well before 1965 (in the 1930s) and was granted a valid export licence by the Jordanian authorities in 1988.”

Ali Altaie, a legal officer who works in the recovery department alongside Hassan, says they have not had any direct contact with Schoyen.

“We have made many attempts to recover these archaeological artefacts through official diplomatic channels, but unfortunately we have not seen a concrete response on this issue,” he says.

“We will certainly resort to other methods, such as international conventions and UN Security Council resolutions. It is important that we spare no effort in this matter.”

As far as Hassan sees it, however, they belong in Iraq.

“They should try to imagine if things were the other way around. If your country was occupied, if looters and Isis came and took everything and sold it to Iraqis. How would you feel?” she says.

It is one of many cases Hassan is chasing. But no matter how many items she recovers, she is fighting an uphill battle. The plunder of Iraq’s history is not yet over.

There are more than 10,000 important archaeological sites across the country, and only 10 per cent have ever been excavated. Thousands are left unguarded, and vulnerable to smugglers.

“Ongoing illicit excavations are the biggest threat to Iraq’s antiquities today. They are happening every week at archaeological sites all over Iraq,” says Bruno Deslandes, a conservation architect at Unesco.

Deslandes says that a lack of coordinated action between different government agencies, and central databases to track missing items, hinders the work of those trying to repatriate missing artefacts. Some also hold on to artefacts longer than is necessary.

“Foreign countries are not proactive enough in physically bringing back items to Iraq. They think they are protecting them by keeping them longer than needed,” he says.

For Hassan, every day that Iraq’s artefacts are not returned feels like a lifetime. On a walk around the museum, she stops at a display case of Aramaic incantation bowls from the 7th and 8th century AD. This is where the bowls from Schoyen’s collection will go, she says, should they ever be returned to Iraq.

“For me, it will be a very big achievement to get them back,” she says. “This country has paid a heavy price. It has paid in blood. At least give us back our history.”