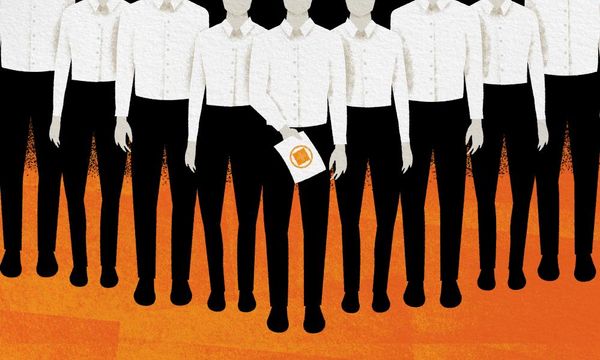

A Korean religious sect that has been labelled a cult by former members is attempting to expand its influence in Australia by targeting young, impressionable people in cafes, on dating apps and on university campuses.

The recruitment drive has led universities to issue warnings to students about the Shincheonji church, as members pose as students and use campus facilities to lure people to Bible study without revealing links to the group.

Guardian Australia has seen training videos and documents that outline the church’s bizarre recruitment methods, which include calling recruits “fruit” and recruiters “leaves”, and which former members claim amount to coercive control.

Diane Nguyen, a former member of Shincheonji who is calling on the federal government to legislate against coercive control by organisations, describes the group as a “doomsday cult”. She says she feels despair for those who continue to be recruited and those still inside.

The Australian branch of Shincheonji did not respond to questions from Guardian Australia, but international chapters have previously denied that the church is a cult. On its global website, the church describes itself as “a temple of God … The Lord of Shincheonji is Jesus Christ who was slain”.

Identifying potential recruits

Church recruiters target universities, churches of other denominations and busy city locations where they approach people on their own, or people wearing religious symbols.

A former Melbourne church member, who only wanted to be identified as “Boa”, said he was targeted through a dating app. He said he met up with a woman he matched with, who brought one of her friends along.

“These two, behind the scenes, were both already members of the church, and I at the time was completely unaware of this,” he says.

“I thought they were just having conversations with me, but now I realise like 90% of the questions were trying to see if I met the criteria for Shincheonji recruitment.

“I unfortunately fell for it.”

Recruiters ask questions to identify factors that might exclude someone, such as having no interest in religion, being LGBTQ+, doing a PhD, being on a temporary visa, or being in debt. PhD students are thought to be too busy to attend recruitment events.

Factors that might make someone a good target include being lonely, religious or open to religion, or newly moved to Australia and on the path to permanent residency.

These were all outlined in a training video for senior church leader recruiters, seen by Guardian Australia. The video tells recruiters to research potential recruits including their culture and interests and to pretend to share those interests.

“Give a lot of compliments, especially at the beginning,” a senior church member says in the video. Several former members spoken to by Guardian Australia described being “love-bombed” – complimented and told they were special – only to later be criticised if they missed anything in an exhausting schedule of Bible study sessions and church events.

During this phase potential recruits are invited to gatherings, often on university campuses, that are not advertised as Shincheonji events. Dozens of posts on online forums include claims by people who say they went to such events but were surprised when they turned into Bible study sessions. During the events recruiters casually mention Bible study, even pulling out a Bible and inviting the potential recruits to a Bible study session at one of their churches, former members said.

Constant contact

Church leader education videos run recruiters step by step through how to keep recruits coming back to Bible study.

Recruiters should call their recruits the night before and again on the day of the Bible study class to ensure attendance, recruiters are told. They should meet the recruit at their home and accompany them to class.

They need to sit next to their recruit during Bible study to prevent interactions with other recruits who may ask difficult questions. Church leaders must pretend to be new to the church as well in order to build rapport.

“You say: ‘I’m like you. I never saw the Bible before,’” recruiters are told in the video.

A former senior leader in the Perth branch of Shincheonji, Matthew Thomas, claims that during this period he was trained to identify if recruits “had a broken family, if they had a history of mental health problems, if they took antidepressants … did they ever live in poverty, did they ever have abusive relationships”.

“I would want to find out their childhood traumas as quickly as possible,” Thomas, who left the church in January after an intervention by his parents, says.

“If you’re able to get someone to that level of conversation, where they feel comfortable enough to share those kind of things with you, it just deepens trust.”

This would allow him to empathise with recruits and offer them support, increasing their reliance on the church.

‘Fruit-to-fruit contact is dangerous’

Church leaders are told in training materials to accompany their recruit as much as possible, including to the toilet, while at church buildings to ensure they don’t interact with other new members, or try to leave.

“Do not let fruits leave the centre to go home alone, but accompany them to their transport and see them off, to minimise fruit-to-fruit contact,” a leader tells recruiters in one video. Offer to drive them home, or to get food with them after class, she says.

“Fruit-to-fruit contact is dangerous. Stick with the fruit. Be close. Close close.”

Leaders are told that only senior church members should be influencing and directly contacting recruits.

In one recruitment video, a church leader describes a former member as a “serpent” and “scary”, because he “didn’t just quietly fall away” when he left the church. He tried to get other church members to leave by “secretly approaching fruits that were alone and didn’t have any leaves with them, and secretly handing them pieces of paper which contained his number on it”.

This is why recruiters must provide regular reports to the church about their recruits, including any resistance to the church’s teachings, along with any interests, hobbies and information about their lives that can be used to retain them, Thomas says.

A training document from the Sydney branch tells leaders that if their recruits challenge the church or if they “receive a slanderous message by text or call, immediately report it to the church”.

Sleep deprivation and exhaustion

In a September sermon delivered to church members in Melbourne and recorded on video, a church leader tells recruits that if they can’t handle the intense schedule of sermons and events, “you need to go back to the education centre”.

The education centre refers to the initial eight to 10-month Bible study course the newest recruits attend, at the end of which, according to former members, they must pass an exam with hundreds of questions and obtain perfect marks to become an official Shincheonji member. Only if they pass is the name of the church, Shincheonji, revealed, Thomas says.

Thomas claims his involvement in the church left him broke, exhausted and unable to see reason. He and other former members spoke of dedicating more than 60 hours a week to it.

Between giving sermons, recruiting, undertaking required education and keeping a vigilant eye on his recruits, Thomas says he at times only got a few hours of sleep a night and constantly had sermon passages running through his head.

If he was late to sermons or education sessions, or seemed tired, he claims he was belittled and chastised by other leaders for being lazy and uncommitted. He described feeling depressed and overwhelmed.

“I was obviously so sleep-deprived,” he says. He got into three car accidents within a couple of years due to passing out from exhaustion at the wheel.

Thomas says once he realised he had been a victim of what he describes as a form of brainwashing and coercive control, he immediately messaged every member of the church he had recruited – more than 70 people, he estimates – and tried to get them to out.

It was a move that he says rapidly saw him blocked by members as word quickly spread.

Thomas says: “The level of guilt I feel for bringing all of these students in is huge. I’m 100% a perpetrator.

“I just felt so angry … sometimes I don’t even know who to feel angry at. All the leaders that had kind of implemented all the mind control on to me – I think are even more brainwashed than I was.”

Do you know more? Contact melissa.davey@theguardian.com

In Australia, the crisis support service Lifeline is 13 11 14. In the US, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is 1-800-273-8255. In the UK, Samaritans can be contacted on 116 123. Other international suicide helplines can be found at befrienders.org