This week (11 - 17 November 2024) the opening of a new exhibition titled ‘De toutes beautés!’ (Of all beauties!) marks the beginning of a three-year partnership between two of France’s preeminent institutions: L’Oréal Groupe and the Louvre Museum. Although arguably, it’s less of an exhibition and more of a proposition on interpreting historical and present-day definitions of beauty through 108 carefully selected artworks in the Louvre’s permanent collection.

Specially conceived text and audio accompaniments complement each of the pieces, which are spread throughout the museum’s eight curatorial departments. Spanning 10,000 years of human history, they are loosely categorised according to cosmetics, objects and rituals, societal transformations and canonical beauty ideals.

Inside ‘De toutes beautés!’ at the Louvre Museum in Paris

The L’Oréal Groupe, with a portfolio of 37 international brands and a global presence across distribution channels from hair salons to perfumeries, turns 115 years old in 2024. ‘Our goal is to look at every person and to create what it is they want, using science and creativity to fulfil the dreams of beauty that people have,’ Delphine Urbach, the group’s director of Art, Culture and Heritage, tells Wallpaper*. If art and visual culture inform society of what is beautiful, then ‘it is our job to come in and help them achieve that. But it’s art that creates the standards,’ she continues.

Strikingly, far from highlighting huge changes to our perception of beauty, ‘De toutes beautés!’ demonstrates how much ancient civilisations are still influencing our modern understanding. As the Louvre’s director of Mediation and Audience Development Gautier Verbeke said in a press statement, the intention behind the show is to ‘trace the threads that bring us back to our time, to its pop culture, in order to better make visitors sensitive, in the present, here and now, to history and the ancient history of forms and images.’

As a result, visitors will see Roman-Greco statues in alabaster marble that have the same rippling six-packs familiar from any modern-day Calvin Klein underwear advert. A diminutive statue in the Department of Islamic Art from around 200 AD is thought to depict someone from the very highest echelons of society; even millennia ago, beauty and status went hand-in-hand. Fast forward to the Renaissance era and Botticelli’s three graces, depicted in his fresco Venus and the Three Graces Presenting Gifts to a Young Woman (c.1483 - 1486), have rosebud lips, dewy eyes and heart-shaped faces.

Pisanello’s Portrait of a Princess (c. 1435 - 1445) looks, at first glance, like the 15th century’s answer to a ‘Croydon facelift’, with an unflattering dearth of contouring about the forehead. But, as an audio description informs, the royal’s hairline had been meticulously plucked according to contemporary fashion.

It is a style that can also be seen across various other cultures in history, such as the Manchus of Qing China. It has also been referenced in the 20th and 21st century in ‘skullets’ sported in punk and goth subculture and also on the fashion runway. (For Rick Owens’ S/S 2020 show, Duffy created a similar look; FKA Twigs also recently sported a half-shaved head with long braids at the back, by hairstylist Louis Souvestre).

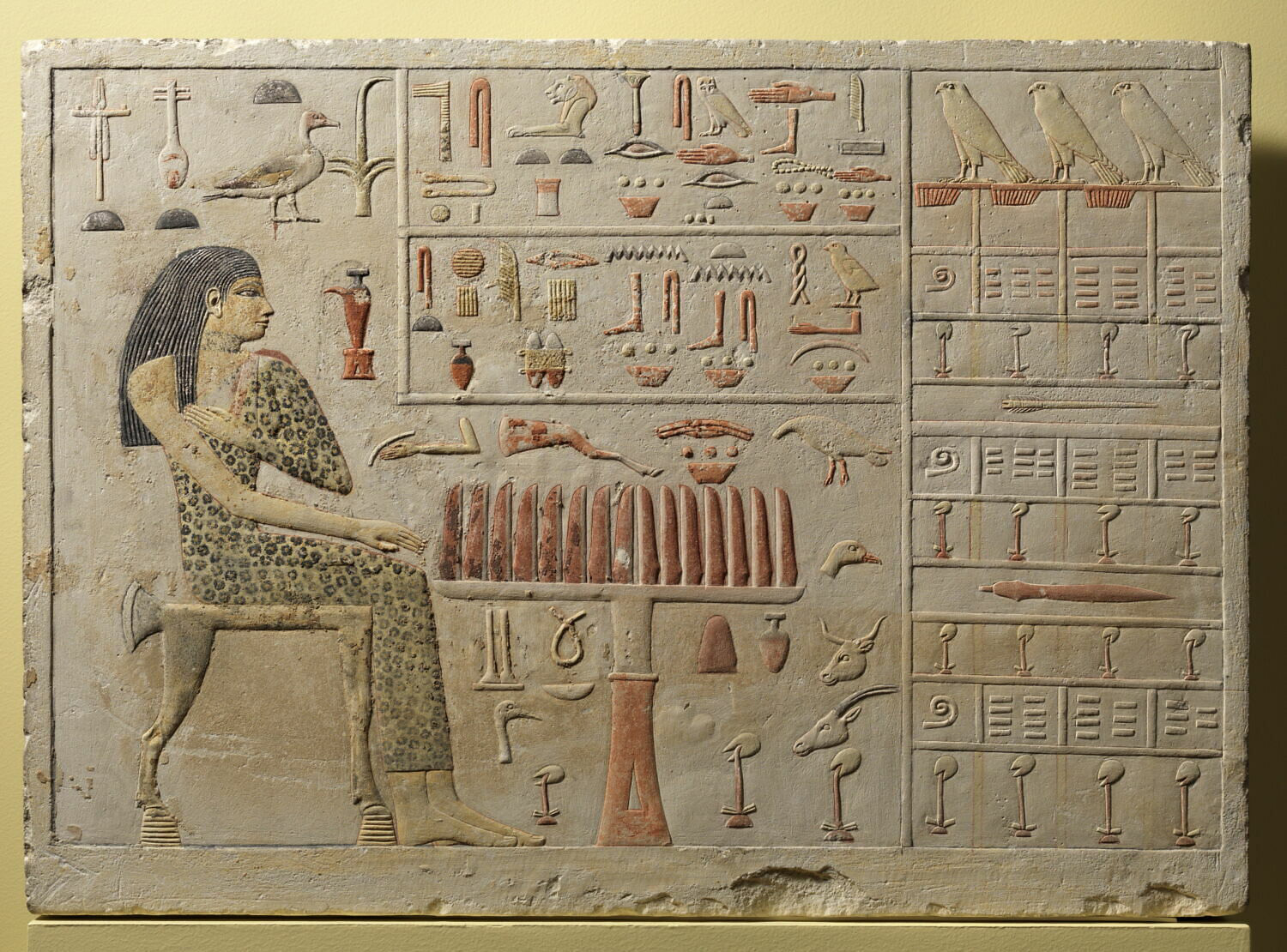

For Urbach, this connection between past and present is also typified by a bust of Meritaten, the first daughter of Akhenaten and Nefertiti. One of the earliest uses of cat-like eyeliner can be traced back to ancient Iraq and Egypt. ‘She makes up her eyes like me – or maybe I make up my eyes like her!’ she says. ‘My mother is Egyptian and as a little girl I saw her applying that black kohl in the same kind of style. Now, my daughter has seen a picture of this piece of art and said: “Mama, it’s you!”’

These personal, emotional links with artworks were something of a driving force in selecting which pieces to highlight. And the curatorial team enjoyed sharing a closeness with the objects. ‘We started with a general idea of the things we would include, according to the official art historical canon, but in the end, everyone in the team would say, “I want that piece in!” because they found they were moved as individuals.’ As a visitor, it is interesting to look around the museum and observe some of the artworks that were not included – did these not represent beauty in their day? Or, are our current prejudices telling us they didn’t?

There were challenging curatorial limitations too: out of all the pieces, only two are confirmed to have been created by female artists. A number of cultures go unrepresented, simply because they are not part of the Louvre’s permanent collection. But perhaps, this further speaks to our canonical understanding of beauty standards, which have largely been dictated by a Westernised male gaze.

But, with the partnership continuing until 2027, this is just the start for the Louvre and L’Oréal Groupe. The latter has also just reissued an updated version of 2009 book 100,000 Years of Beauty, published by Éditions Gallimard and edited by anthropologist Elizabeth Azoulay, which brings together contributions from 400 authors from diverse cultures across approximately 35 nationalities over five volumes.

‘Art is the first witness to the human quest for beauty. Both inspire each other, both speak of humanity and its evolution, and both reflect the questions of that humanity,’ says Urbach. ‘As a result, art has always held a special place in our desire to shed light on the subject of beauty in all its diversity, to share it and to highlight the deeper meaning of self-beautification and the transformations of appearance in relation to oneself, to others, and to the world.’