Warning: this article contains distressing detail about people's injuries

A badly burned toddler screaming for the mother he doesn’t know is dead – and screaming because doctors do not have enough painkillers to relieve his suffering. An eight-year-old boy whose brain is exposed as bombing damaged parts of his skull. A teenage girl, her eye surgically removed, because every bone in her face is smashed. A three-year-old double amputee, whose severed limbs are laid out in a pink box beside him.

And in the background is the stench of rotting flesh as maggots “creep out of untreated wounds”.

This is the daily reality at the European Hospital inside the southern Gaza city of Khan Younis, as described by veteran British war surgeon Tom Potokar, who works for the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC).

While the United Nations warns that the humanitarian situation in Gaza is “apocalyptic”, the Israeli military has expanded a ferocious ground campaign from the north of the besieged territory into the south, where an estimated 1.9 million Palestinians have been displaced.

The Israeli prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, has vowed to continue the war until the army destroys Hamas, which runs the Strip and launched a deadly attack on southern Israel on 7 October in which 1,200 people were killed and another 240 were taken hostage.

Israel launched its heaviest-ever aerial bombardment of Gaza in the wake of the Hamas attack. And in recent days, Israeli forces have started to storm Khan Younis, the largest city in southern Gaza, launching what is believed to be the biggest ground assault since a fragile seven-day truce collapsed last week.

Inside the European Hospital, one of the main medical centres servicing the city and surrounding areas, medics struggle to treat the “relentless” stream of wounded, Dr Potokar says.

Nearly half of them are children.

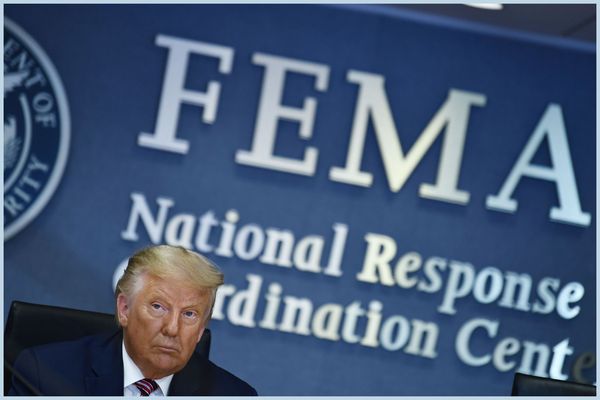

Evidence of some of the damage from airstrikes in Khan Younis— (Reuters)

“I’ve lost count of the number of children we have treated who have horrific injuries, burns, amputations, who've lost their whole family,” Dr Potokar tells The Independent from inside the hospital compound which, like other medics, he has not left for five weeks.

Palestinian and international medics are sleeping on the floor of the nursing quarters, living off packets of noodles and working 14-hour shifts, he explains. One night Dr Potokar says he was nearly killed by shrapnel which came through a window.

Some medics, including nursing staff and surgeons Dr Potokar worked with, have been killed alongside dozens of members of their family. At least one of the 100 ICRC staffers working in Gaza has also been killed.

This is Dr Potokar’s 14th time working as a medic in Gaza. He has worked in the field as a surgeon in Somalia, Syria, Afghanistan, and Yemen, but this conflict “is without doubt the worst”.

“I have seen far too many children whose lives have been destroyed,” he says. “I’ve treated a four-month-old with significant burn injuries. I treated an eight-year-old that had an open fracture of his skull with an exposed brain. It is just awful to see and it’s so relentless. It's just not stopping, they keep coming in every day.”

Recently Dr Potokar was treating a burns patient in the intensive care unit who had fled the north of the country and whose wounds were septic as the dressing had not been changed for days. On the bed next to the burns patient was a three-year-old boy.

“He had [two] above-knee amputations done the night before from an airstrike. I found out afterwards that his father had also had an amputation and the rest of his family didn't make it,” Dr Potokar says. "This is not a one-off event.”

British war surgeon Tom Potokar— (ICRC)

The pause in the fighting during the week-long ceasefire brokered by Qatar had provided some respite to millions of Palestinians who live in the 42km-long enclave. Dozens of hostages, including elderly women and children aged just four years old, were released. The ICRC facilitated the transfer of 104 hostages and 154 Palestinian detainees involved in the exchange.

But since the truce expired on 1 December, Israel has pushed into southern Gaza, as well as continuing operations in the north. Nearly 2 million Palestinians – ordered by Israel to take shelter in the south – are now crammed “into ever-diminishing and extremely overcrowded places in unsanitary and unhealthy conditions,” the UN’s rights chief Volker Turk warned on Wednesday.

"Humanitarian aid is again virtually cut off as fears of widespread disease and hunger spread,” he added.

Israeli military spokesperson Jonathan Conricus told CNN that Israeli forces were targeting Hamas command and control centres, weapons storage and logistics facilities and that they had asked Palestinians to evacuate to a special humanitarian zone in southern Gaza near Khan Younis. He admitted this “isn't perfect but it is the best, currently available solution that we have”.

The health ministry in Hamas-run Gaza said the death toll had soared since the resumption of hostilities, with more than 1,200 killed in the last week alone. In total, health officials say Israel’s offensive has killed more than 16,000 Palestinians, 70 per cent of them women and children.

Aid group Save the Children says that the child death toll in Gaza is so high it surpasses the annual number of children killed across the world's conflict zones since 2019.

Jan Egeland, secretary general of the Norwegian Refugee Council said on Tuesday that “the pulverising of Gaza now ranks amongst the worst assaults on any civilian population in our time and age”.

The United Nations children's agency said this week Gaza is the most dangerous place in the world to be a child. And it will only get worse.

A child is taken into hospital in Khan Younis— (Reuters)

At the European Hospital, at least 360 people are on the waiting list for an operation now, an “impossible number to deal with,” says Dr Pokotar.

“It’s almost like a perfect storm of neglected wounds and then the patients getting malnourished as well which means they won't heal. They've had different procedures at different places and been transferred from one place to another,” he adds.

This is compounded by staff shortages as medics are killed at home, or prevented from getting to the hospital because of bombing and destroyed roads.

The nurse who had helped him with the three-year-old double amputee was killed three nights ago along with 12 members of his family, Dr Pokotar says. A senior plastic surgeon, who was also a colleague, was killed with 30 members of his family in an airstrike four weeks back. Every day, nursing staff and surgeons are treating family and friends that are brought into the hospital – many do not make it.

“It's difficult to find somebody who hasn't lost somebody close,” he adds.

“There are just too many patients and not enough staff, not enough theatre time to treat all of them. So you have to prioritise.”

Infections are now running rife through hospitals as wounds are not being tended to in time; there is an “overwhelming” number of patients with complex injuries that have been neglected.

Dr Pokotar says anyone who would doubt the devastating impact on civilians would change their mind if they spent a day in his wards.

“If you could bring any person here who was not sure, and you place them here, and you got them to smell the stench of rotting flesh, to see the sight of maggots creeping from wounds of a person who has necrotic flesh and to hear the screams of kids because there's not enough analgesia [painkiller], and they want their mum, who's not going to appear because she's dead – I think people might feel a bit different about this.”