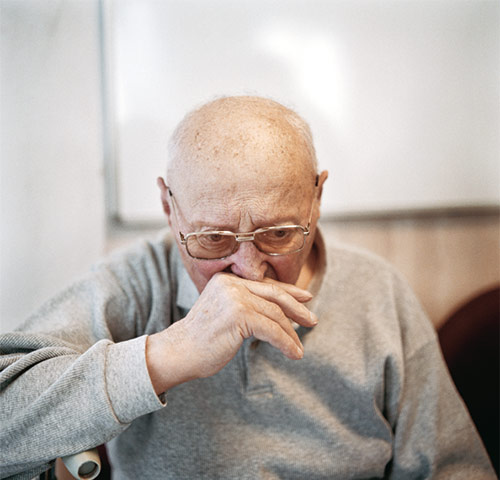

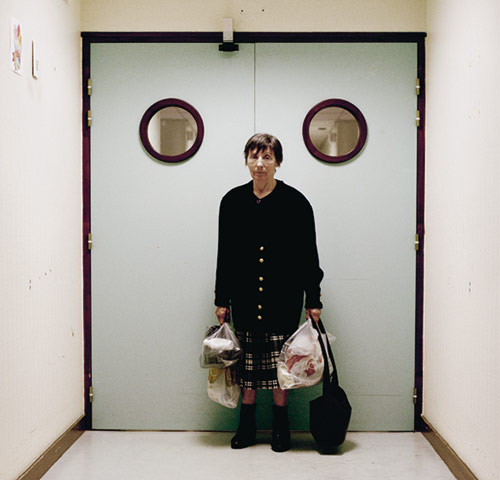

Photograph: Maja Daniels/Picturetank

Photograph: Maja Daniels/Picturetank

Photograph: Maja Daniels/Picturetank

Photograph: Maja Daniels/Picturetank

Photograph: Maja Daniels/Picturetank

Photograph: Maja Daniels/Picturetank

Photograph: Maja Daniels/Picturetank

Photograph: Maja Daniels/Picturetank

Photograph: Maja Daniels/Picturetank

Photograph: Maja Daniels/Picturetank

Photograph: Maja Daniels/Picturetank

Photograph: Maja Daniels/Picturetank

Photograph: Maja Daniels/Picturetank

Photograph: Maja Daniels/Picturetank

Photograph: Maja Daniels/Picturetank

Photograph: Maja Daniels/Picturetank

Photograph: Maja Daniels/Picturetank

Andrea Gillies is the author of Keeper: Living With Nancy – A Journey Into Alzheimer’s, published by Short Books at £7.99. It won the 2009 Wellcome Book Prize, and the 2010 George Orwell Book Prize.

Photograph: Maja Daniels/Picturetank