With the world experiencing inflation levels not seen since the 1980s, central banks are caught between warning of the dangers of an 1970s-style inflationary spiral, and contributing to that spiral by talking about it.

It’s a problem in any part of the economy where expectations shape outcomes.

On one hand, central banks including Australia’s Reserve Bank say they fear the return of “inflation psychology” – in which expectations of high inflation drive high inflation.

The Bank of International Settlements (the central bank for national central banks) warned in its 2022 annual economic report:

We may be reaching a tipping point, beyond which an inflationary psychology spreads and becomes entrenched. This would mean a major paradigm shift.

Such warnings, known as “open mouth operations”, are part of a central banker’s policy toolkit, the hope being that people will heed the threat and moderate their spending, negating the need for the painfully blunt instrument of hiking interest rates even more.

On the other hand, the very notion of inflationary psychology is bound up in people being emotional, and not necessarily susceptible to “rational” persuasion.

Read more: 1970s-style stagflation now playing on central bankers' minds

As behavioural economists, we can see the dilemma in warning about inflationary psychology, given the very concept is about self-fulfilling prophecies.

The inflation we are facing is real, caused mainly by supply shortages due to COVID and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

It is how we respond to them that either fuels or chokes further inflation.

Cognitive illusions

Behavioural economists know that whereas rising prices needn’t be a problem so long as all prices (and wages) are climbing at the same rate, we notice nominal stated prices much more than we notice real (inflation-adjusted) prices.

In the 1920s, US economist Irving Fisher dubbed this “the money illusion”.

Nobel Prize winners Akerlof and Shiller have demonstrated that the phenomenon is widespread.

Even professional decision makers behave as if nominal prices matter most. Loan contracts, for example, are usually not indexed to inflation, meaning the real value of what’s owed usually shrinks.

Selective perceptions

Focusing on nominal rather than real values gets entangled with selective perception. We focus on what matters most to us, so we mainly consider the prices (and wages) we are familiar with.

This is demonstrated by behavioural experiments showing women are more likely to focus on the price of milk and men on the price of beer and fuel.

Another cognitive bias is the availability heuristic – the mental shortcuts we make to assess the probability of future events.

This phenomenon was first identified by Israeli psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky. People tend to exaggerate the likelihood of events they find easy to imagine - such as being killed by a shark.

So much talk about the threat of inflation, and powerful images of hyperinflation - such as people wheeling wheelbarrows full of cash - can similarly influence people’s expectations.

Inflation psychology missing

So far, there’s not much inflation psychology in Australia.

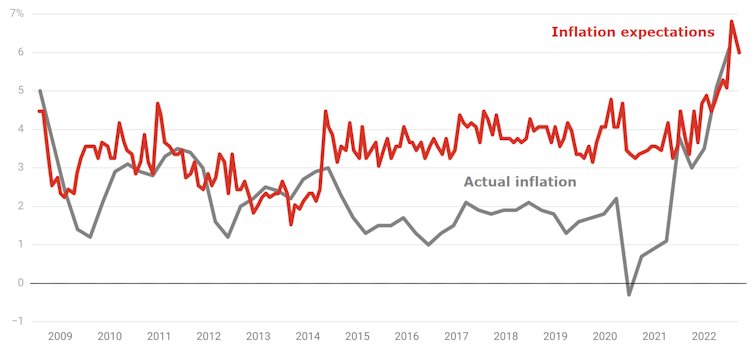

Typically the Melbourne Institute’s survey of inflation expectations has come up with an annual rate of about 4% at times when actual inflation has been about 2%.

Recently, expectations have climbed with actual inflation to peak at 6.7% when actual inflation was 6.1%.

Since then, in July and August, inflation expectations recorded by the survey have declined, to 6.3% in July and 5.9% in August.

Actual inflation versus expectations

Taken literally, this means Australians expect inflation to fall.

More confidently we can say that consumers’ expectations are in line with reality, rather than above it as has traditionally been the case.

The world would be a much easier place for central banks if people were rational.

They are not, but for the moment (based on what they are saying) they don’t seem to be getting carried away.

Read more: Australia's inflation rate is to go monthly. Be careful what you wish for

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.