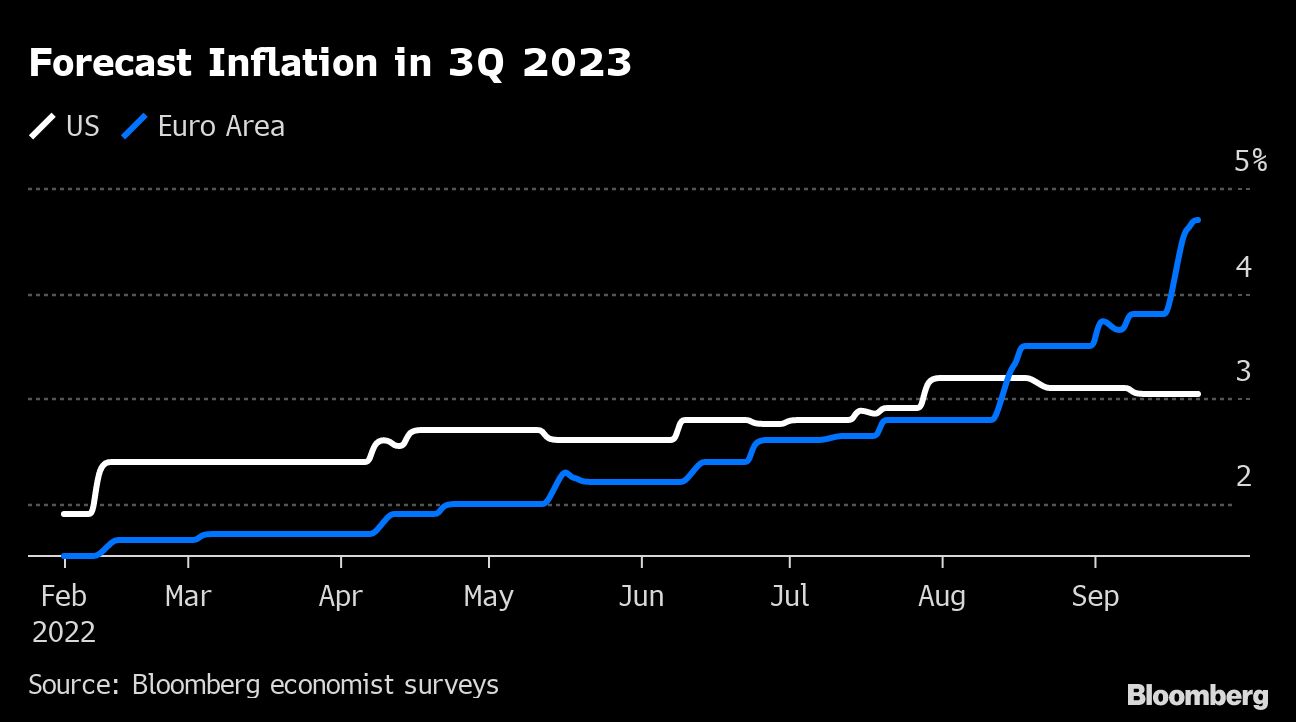

When pandemic inflation took off last year, it was seen as more likely to stick around in the US -- where stimulus was much bigger and consumer demand stronger -- than in Europe. But the energy crisis has upended that picture.

Euro-area price increases have now outpaced the US for two straight months. The gap likely widened in September, when Europe-wide inflation hit 10% while in Germany it accelerated to 10.9%. US numbers aren’t due out for another 10 days.

Even more strikingly, economists looking a year ahead now see Europe’s inflation lingering close to 5%, while in the US it’s expected to drop back to around 3%.

“In the near term, eurozone inflation actually looks uglier than the US,” says Robin Brooks, chief economist at the Institute of International Finance.

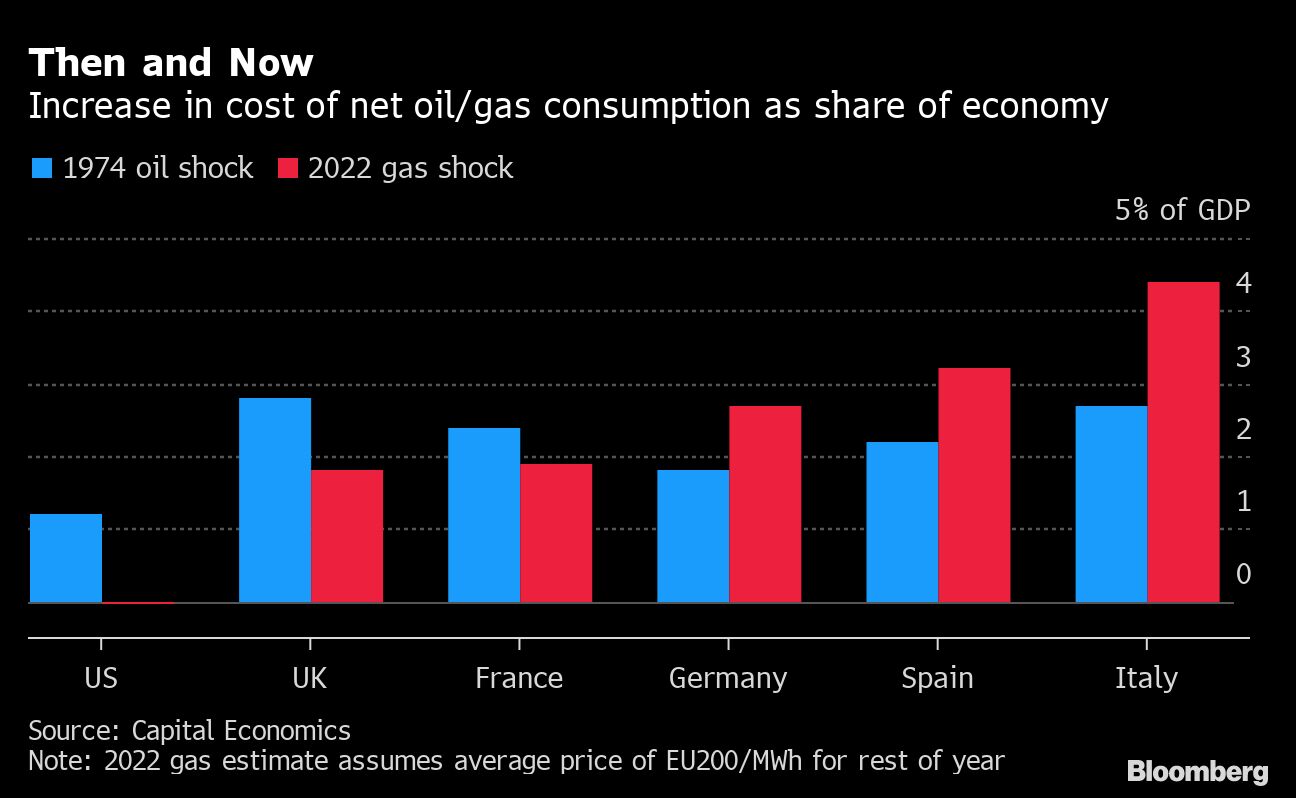

The reason is Europe’s natural-gas crunch, the result of shortfalls in Russian imports that got worse after the invasion of Ukraine. That sent electricity prices soaring too, helping drive up costs in pretty much every corner of the economy -- with the result that inflation is now broader in Europe, as well as higher.

Beyond all these numbers, Europe ultimately has a different kind of inflation than the US -– one that’s almost entirely imported via soaring commodity prices, rather than stoked at least in part by robust consumer spending and tight labor markets at home. That distinction has major consequences for policy makers and investors, as well as households and businesses.

‘Just Not There’

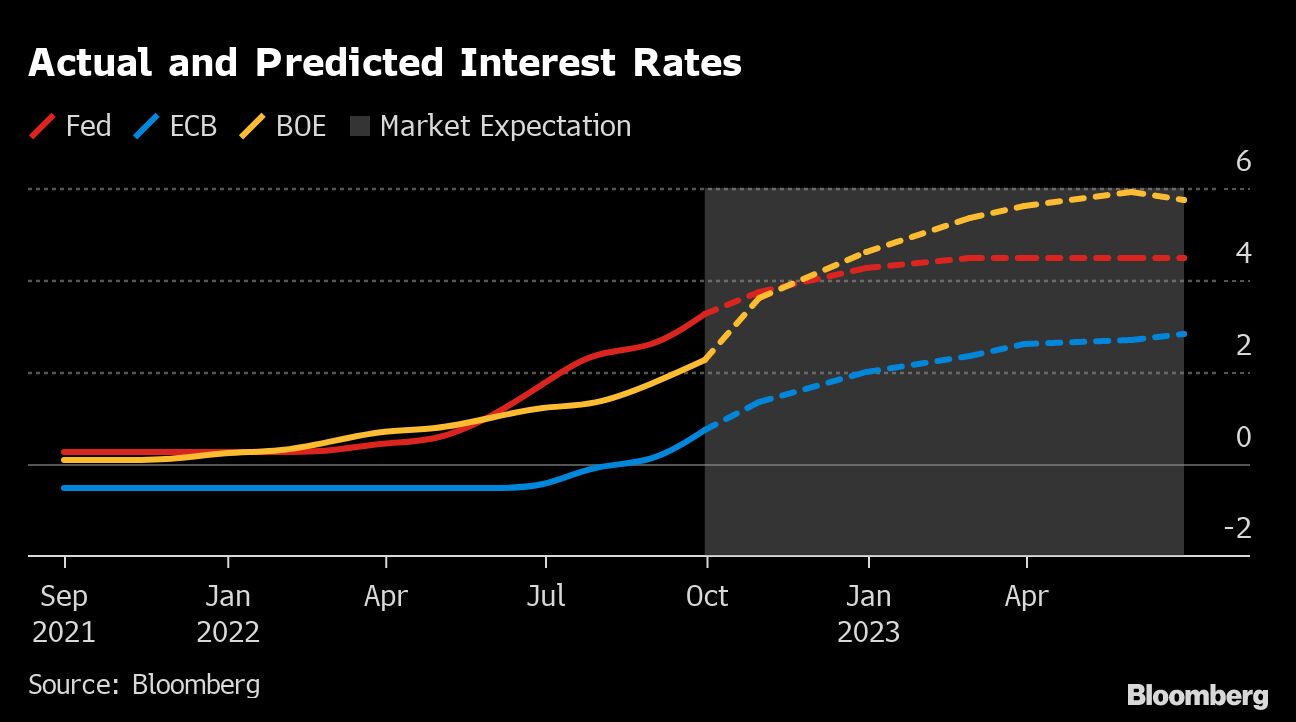

It means Europe’s central bankers – who are applying the same inflation medicine as their US peers, by rapidly raising interest rates – have less ability to address the root problem, and run more risk of hurting their economy in the attempt.

Fiscal policy is diverging too, with European governments forced to add stimulus to cushion the blow from soaring energy bills. And for ordinary Europeans, standards of living are set to fall even further behind their American peers.

On the face of it, the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank – though they set off from different places at different times -- are now on a similar track.

Both raised rates by 75 basis points at their last meeting. Both are likely, in the view of markets, to do the same next time around. Both talk up the importance of keeping expectations for future price increases in check.

“What the two central banks have in common is, they are very much focused on spot inflation, on elevated numbers right now,” says Brooks. “They’re not focused enough on underlying dynamics, the leads and lags of policy.”

He expects the euro area to slide into recession imminently, while the US avoids a slump –- and says that outlook should prompt a reassessment of the ECB’s inflation-fighting approach. “With GDP about to drop, who are the people who are going to push up wages with their demands?” says Brooks. “Which businesses are going to raise their margins? The conditions for a wage-price spiral are just not there.”

In fact, European wages have been rising more slowly than American ones, even though prices are now rising faster. That’s another sign that inflation is taking a bigger bite out of living standards in Europe than in the US, where many workers got a pay bump in tight pandemic labor markets.

‘Longer to Fall’

For now, European central bankers seem just as committed as their Fed peers to tighter monetary policy -- and some analysts reckon they may end up having to keep it for even longer.

“Core inflation is likely to take longer to fall in Europe than in the US, partly because Europe will continue to suffer from a bigger energy supply shock,” analysts at Capital Economics wrote last month. “While we expect the Fed to cut rates in the second half of 2023, we doubt that the BoE and ECB will be able to do so before 2024.”

The hawkish turn in Europe hasn’t prevented a slump in the continent’s main currencies, which adds to the cost of imported inflation.

Since mid-August, market expectations for the interest-rate gap between the Fed and the ECB have narrowed, as the latter signaled faster hikes in the pipeline. But that didn’t halt the euro’s decline: it plunged another 5% against the dollar in the period.

Essentially, investors have been betting that today’s inflationary energy shock will differ from the one that hit Western economies across the board in the 1970s -- because now, unlike then, the US is an energy giant which produces its own fuel, while Europe still has to buy it from outside.

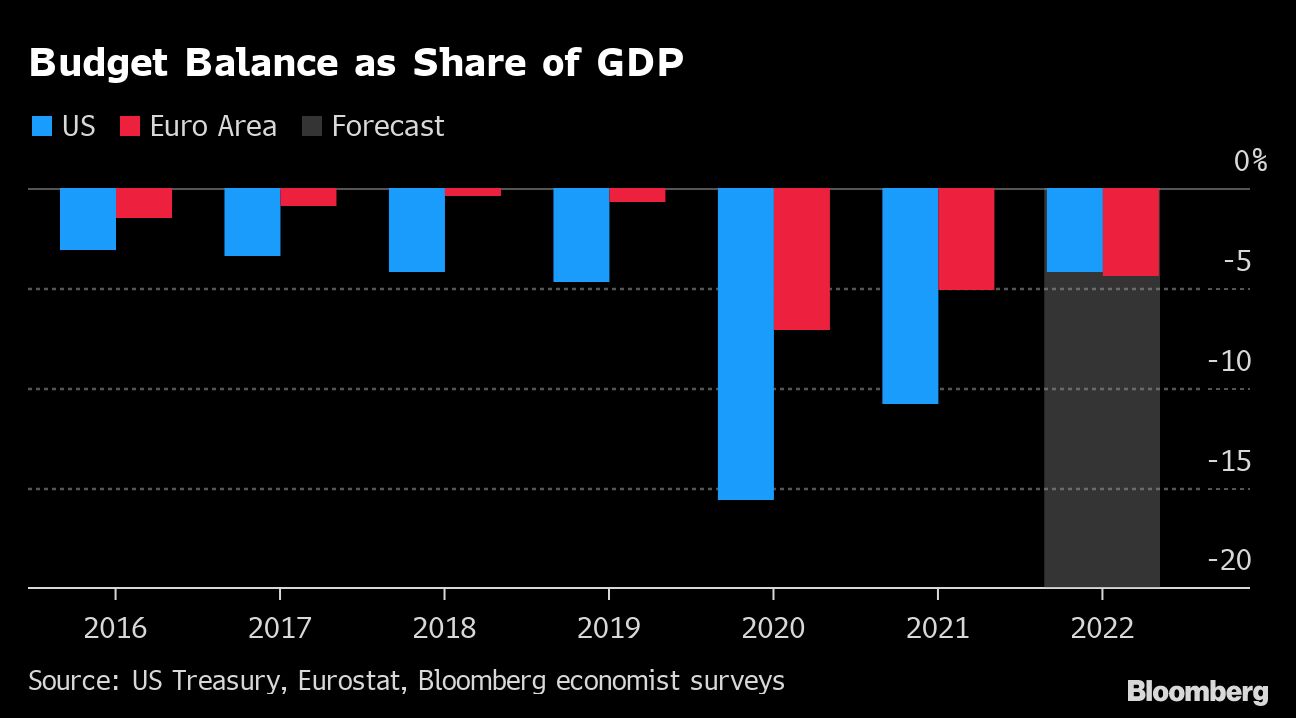

That divide shows up in fiscal policy too. The US has been withdrawing stimulus, but Europe is having to add more of it, with energy subsidies to cushion the blow and make sure households don’t freeze -- and businesses don’t shut down -- in the coming winter.

‘Decisive Way’

The cost of doing that is likely to add up to at least 5% of GDP a year, estimates Dario Perkins, an economist at TS Lombard in London.

One likely result: the euro-area’s combined budget deficit is forecast to be bigger than America’s this year – the first time that’s happened since before the Great Recession.

Germany last week announced it will borrow an extra 200 billion euros ($196 billion) to cover the cost of capping natural-gas prices. The UK, where new Prime Minister Liz Truss has spooked markets by proposing tax cuts as well as energy subsidies, appears headed for even larger shortfalls.

All that extra fiscal spending will help avert the kind of deep slump that would force European central bankers to do a U-turn and abandon their plans to keep borrowing costs high, Perkins argues. The upshot will be a policy mix that’s the complete opposite of the pre-pandemic decade, when austerity was twinned with zero interest rates.

“We’re in a radically different world now,” with fiscal and monetary authorities set for a kind of “tug-of-war,” he says. “The more governments ease, the more worried central banks will be about inflation, so the more they’ll be tightening.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.