The worst is over, economies are recovering and high inflation rates are likely to ease. So, the right response now is a modest rise in interest rates from their long-running, absurdly low levels. A bold world must embark on a radical and rapid remake to a net zero emissions economy.

Opinion: The economy and financial markets, here and abroad, have got off to a rocky start this year. As we seek our most effective responses, some big themes can help guide us. They include:

- Change now is very different from the past. It’s far deeper and more complex, faster and more inter-connected than ever before. That’s true within countries and between countries.

- Some solutions that worked well in the past are far less effective now.

- Only systemic solutions will work now. Quick, partial and temporary fixes will only make things worse.

- We must have whole-of-society responses. Governments and central banks, businesses and civil society all have roles to play, co-operatively.

It also helps to keep current conditions in perspective:

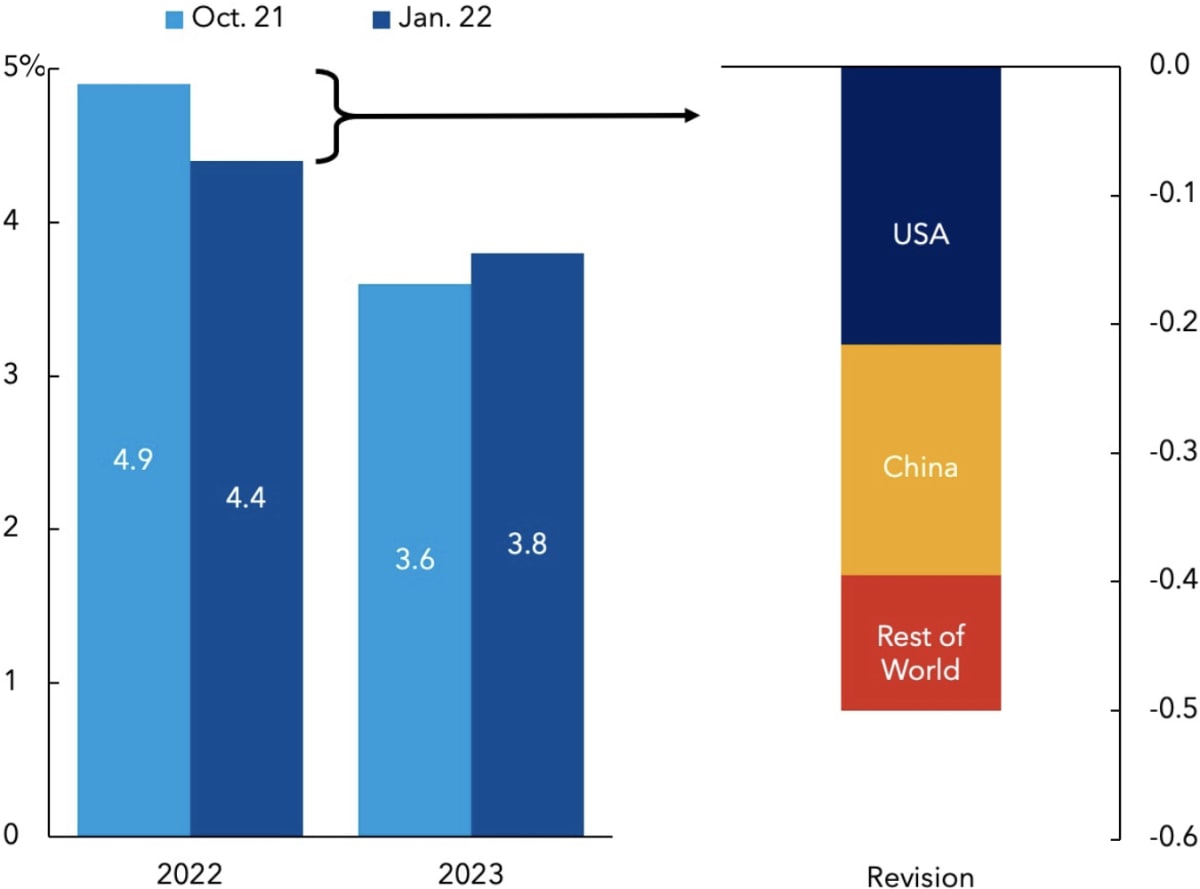

► Yes, the IMF recently downgraded its global economic forecast for this year. But it still expects growth to be well above trend at 4.4 percent. Within that, it reckons high-income countries will grow by 3.9 percent and emerging and developing countries by 4.8 percent. Likewise, growth here in New Zealand will likely be above trend.

A disrupted global recovery

► Yes, central banks have stopped the massive support they had to give their economies during the height of the pandemic 2020-21. But the worst is over, and economies are recovering. So, the right response now is a modest rise in interest rates from their long-running, absurdly low levels.

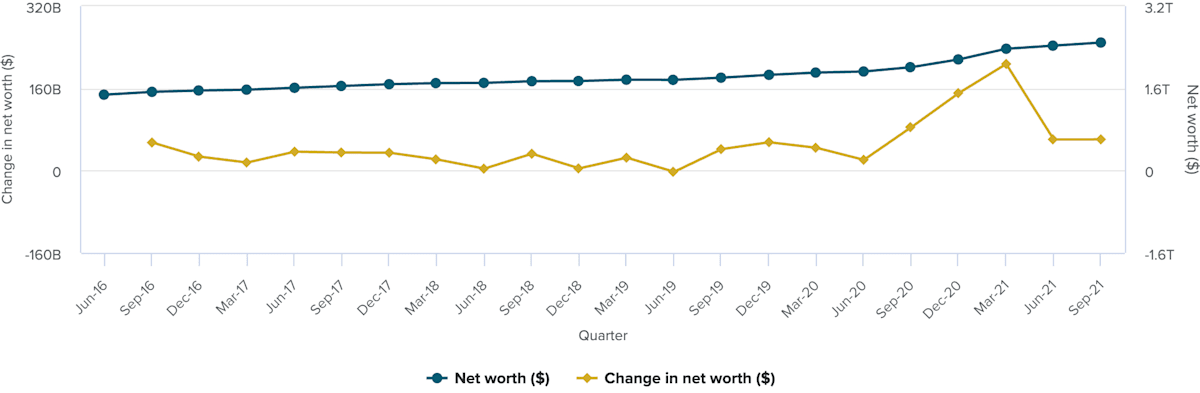

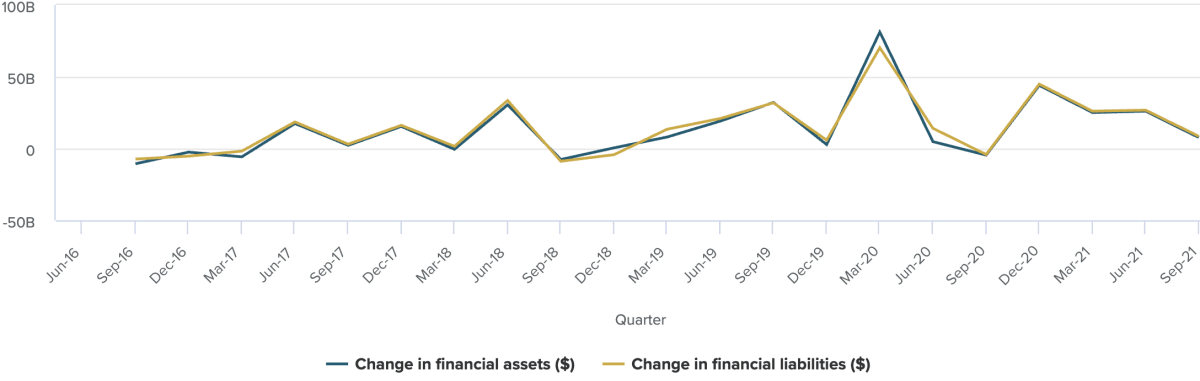

Moreover, central banks’ creation of money to support economies has been the biggest driver of asset price inflation, particularly in equities and property. That’s a global phenomenon, including here. Statistics NZ’s latest national accounts data, out this week, shows how well the balance sheets of businesses and households fared through the pandemic thanks to the massive government and central bank financial injection into the economy. But the outright losers were clearly poorer households without property and investments.

Household net worth ($)

Financial business enterprises quarterly change in financial assets and liabilities ($)

In this segment on RNZ’s Nine to Noon, Kathryn Ryan and Bernard Hickey had an illuminating discussion of the data on Thursday.

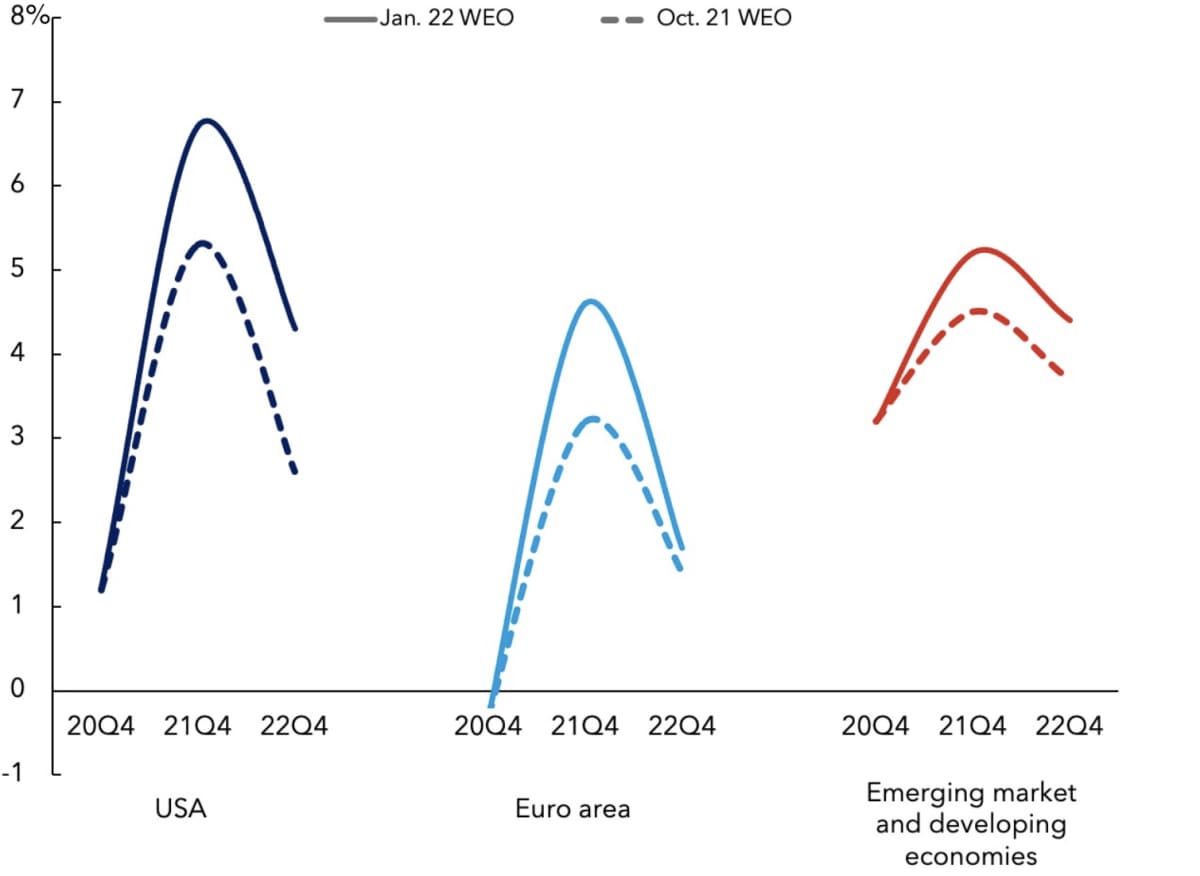

► Yes, inflation, here and abroad, is running at its highest level in decades. But the main contributing factors – notably high energy prices and supply chain constraints – are likely to ease this year.

Inflation revised higher

There is a risk that expectations of worsening inflation gets baked into some economies. However, there is a strong argument to make that economies are now far more flexible and innovative than they were in the early-1980s when double-digit inflation was deeply rooted in the psyche and practices of households, businesses, and governments.

Then, swingeing interest rates and draconian economic reforms were needed to drive big, beneficial improvements in rigid economic systems and behaviour.

Now, hopefully, our economies are far more flexible so we can fast-forward their development to alleviate inflationary pressures without the need for very blunt instruments such as eye-watering interest rates.

Current labour markets and wage inflation, though, are more problematic and puzzling, as many economists concede. One example is this recent piece by Paul Krugman. But if employers innovate so they can deliver better pay, training and conditions then productivity, profits and job satisfaction will improve to the benefit of employers and employees and economies and nations at large.

► Yes, global stock markets have lost some ground, driven by worries of rising interest rates and slowing economies. But they have enjoyed one of the biggest, longest bull markets ever. Since the end of the last extended bear market in March 2009, S&P 500 US stock market index had risen by 550 percent before its recent modest decline. On Thursday, I discussed this and other crucial features of current markets on this webinar hosted by Sharesies

If stock markets around the world begin to show greater rationality and discernment, then hopefully more companies investing in our big challenges will be more thoughtfully and strongly supported by investors. Such a shift is particularly urgent for those companies leading the transformation to a net zero emissions economy.

That remake of the economy must be radical and rapid. It’s one of the best examples of the four big themes about change outlined at the top of this column. A report out this week by McKinsey, the global consultants, lays out the scale of the task.

“While the immediate tasks ahead may seem daunting, human ingenuity can ultimately solve the net-zero equation, just as it has solved other seemingly intractable problems over the past 10,000 years. The key issue is whether the world can muster the requisite boldness and resolve.” – McKinsey report

It examines sectors that account for 85 percent of greenhouse gas emissions in 69 of the largest countries, and examines how demand, spending, investment and jobs would need to change in order to reach net zero emissions by 2050.

For example, between 2021 and 2050, capital expenditure on assets for energy and land-use systems to achieve net-zero would reach US$275 trillion (NZ$420 trillion). The spend would average some US$9.2 trillion annually, almost three times greater than the current rate.

An additional US$1 trillion on today’s annual spending would also need to be relocated from high-emitting sectors to new low-carbon assets. McKinsey estimates that increase is equivalent to half of the recorded profits from corporates globally in 2020.

Moreover, the spending has to be front-loaded to deliver drastic levels of decarbonisation. It would need to rise from 6.8 percent of GDP today to 8.8 per cent between 2026 and 2030, after which the rate would slow. While these spending requirements are large, McKinsey believes they will have “favourable return profiles”.

One of the keys to reducing these costs is reallocating spending and job opportunities from high-emitting sectors to low-carbon markets. The report states that high-emission products and operations currently generate around 20 per cent of global GDP, which would need to be massively realigned to reach net-zero. The transition, the report states, could result “in a gain of about 200 million and a loss of about 185 million direct and indirect jobs globally by 2050”.

“The rewards of the net-zero transition would far exceed the mere avoidance of the substantial, and possibly catastrophic, dislocations that would result from unabated climate change, or the considerable benefits they entail in natural capital conservation. Besides the immediate economic opportunities they create, they open up clear possibilities to solve global challenges in both physical and governance-related terms. These include the potential for a long-term decline in energy costs that would help solve many other resource issues and lead to a palpably more prosperous global economy,” the report states.

“More importantly, they presage decisive solutions to age-old global economic and political challenges as the result of the unprecedented pace and scale of global collaboration that such a transition would have required. And while the immediate tasks ahead may seem daunting, human ingenuity can ultimately solve the net-zero equation, just as it has solved other seemingly intractable problems over the past 10,000 years. The key issue is whether the world can muster the requisite boldness and resolve to broaden its response during the upcoming decade that will in all likelihood decide the nature of the transition.”

So, yes, keeping alert to current conditions is vital. But the very best way to respond is to see in them the opportunities for meeting humanities’ challenges.