In 2015, when I quit my job as the editor of a fashion magazine to study photography in Paris, I was a senior student. Very senior. Imagine my surprise then when my international classmates — aged mostly between 18 and 28 — were all shooting film, something I’d given up in 2006.

Like most photographers pre-digital era, however, I had shot slide, colour negative, and black and white film. I had push processed, cross processed, and even taken a course in film processing and printing. I thought I was stone age, except, as it turned out, that’s where the world now wanted to be.

As I was swept up in its wake — unearthing an old medium format twin lens reflex Yashica gifted by an uncle, its leather cover falling apart, and purchasing boxes of 120 Kodak Portra — I could see film photography take off.

There were many signs. First, the 25.5 million posts on Instagram under the hashtag #filmisnotdead. Then, the reissue of out-of-production film and film cameras such as Kodak Ektachrome and the Leica M6, respectively. There were also the soaring sales of Fuji Instax for instant photography and the 2017 return of Polaroid as Polaroid Originals, after its 2001 bankruptcy. And then, in 2022, Ricoh Pentax announced it was developing a new 35mm film camera.

In India, in 2016, by popular demand, Radhakrishnan Vijayakumar, Group CEO of Srishti Digilife, had started to import and sell film from Kodak, Ilford and Lomography, and develop chemicals for the film in the Indian market. Since then, Ilford’s revenues have grown from ₹50 lakh to ₹4.5 crore, while Kodak has shot up from ₹85 lakh to ₹4.8 crore last year.

Join the community

India has seen a boom, too. In the past three years, several WhatsApp and Facebook groups for enthusiasts and professionals have sprung up — to share resources, exchange ideas, and troubleshoot problems. Film photography workshops have become the order of the day as have film processing studios, such as Zhenwei in Mumbai (founded in 2020, it processes around 300 rolls of film every month).

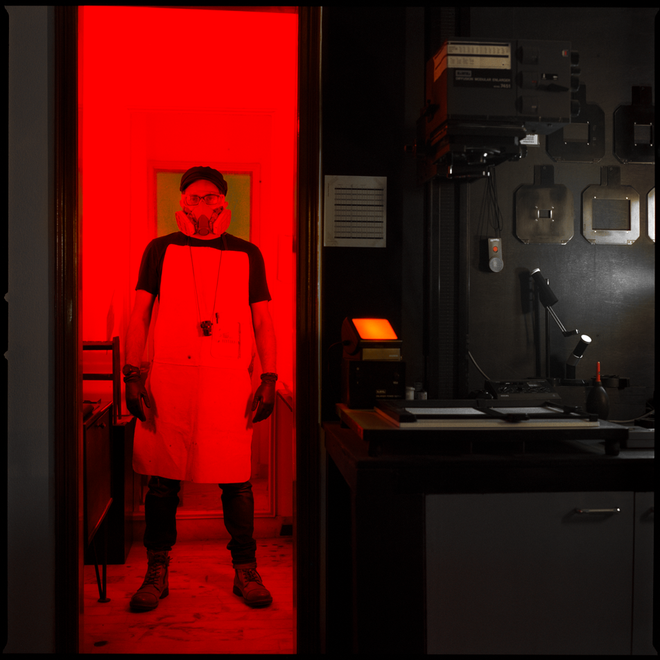

Community dark rooms have also mushroomed across the country, from Siliguri to Goa, Delhi, Gurugram, Chennai, Bengaluru, and Puducherry. Many of these spaces, such as the Chennai Photo Biennale (CPB) and Zhenwei, sell their own respooled film (bought in bulk, cut, and spooled onto new canisters for very economical rates, given that film prices have increased dramatically year-on-year).

Artist and photographer Sasikanth Somu, 56, runs a community darkroom at the Centre d’Art in Auroville. Started during the pandemic, at the tail end of 2020, he holds workshops as well. One of the reasons film is back, he feels, lies in it being the antithesis of today’s instant culture — where you can shoot, upload and receive appreciation in less than a minute. “My students get hooked to that process of not seeing the image straight away, of waiting to process their film rolls, print photographs, and only then see the positive images.”

Menty Jamir, a photo-artist and creative director based between Delhi and Shillong, started shooting film three years ago when friend and Magnum photographer Sohrab Hura gave her his medium format camera with 20 black-and-white rolls, as she was heading home to Shillong during the pandemic. In 2021, out of curiosity, she signed up for the Photo.South.Asia darkroom workshops, initiated and mentored by Delhi-based photographer Srinivas Kuruganti — to learn more about the analogue approach, print-making, and gain the confidence to shoot film. “The change in form itself can enhance one’s way of seeing and open a fresh perspective,” she says.

In short, like any self-respecting hero, film photography has risen victorious from the dead. Except that there’s a twist to the tale. It turns out the hero is not film photography as much as analogue photography. What’s the difference? The latter encompasses all the processes that were used to capture and create images from the 19th century onwards, well before the invention of the 35mm camera. Some of them, such as cyanotypes (a contact printing process that produces cyan blue prints), don’t even use a camera.

Alternative processes, or historic processes, as they are called, are having their moment in the sun. Popular filters on social media say something about the likeability of the medium. And as if to prove the point, the ongoing fourth anniversary celebrations of Museo Camera in Gurugram include exhibitions of historic cyanotype, gum bichromate, and albumen prints.

For the love of the dark

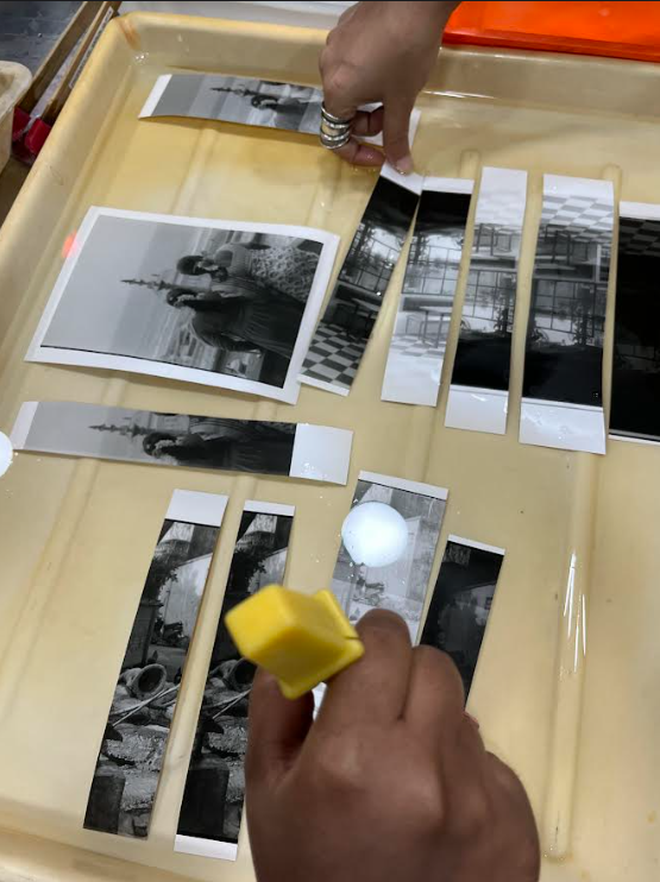

For Varun Gupta, 41, analogue artist, director and co-founder of Chennai Photo Biennale — which has just moved into new premises that offers a community darkroom as well as workshops and kits for alternative processes — it is the element of chance that accounts for the appeal of alternative process. “With digital, everything has become so controlled that one finds it almost impossible to truly surrender. [With alternative process] you’re not really sure what you’re going to get; you modify and troubleshoot. It’s also very tactile.”

The pandemic was a tipping point for alternative processes, he says. Gupta saw a global spike in interest in 2020. That was also the year CPB started doing cyanotype workshops. At the end of the first wave, the sessions, which took place in parks, attracted participants to the tune of a few hundred at a time; Gupta attributes it to digital revulsion. “We wake up in the morning and stare at a phone, before you sleep you stare at it. It’s this circle of consumption on screens that has made us collectively yearn for something analogue.”

In the past three years, they have taught the process to more than 2,000 people. CPB now sells two types of cyanotype kits (starting from ₹1,200) and has an e-learning course, too. Gupta also teaches salt printing and Van Dyke brown and is looking forward to learning the gum processes.

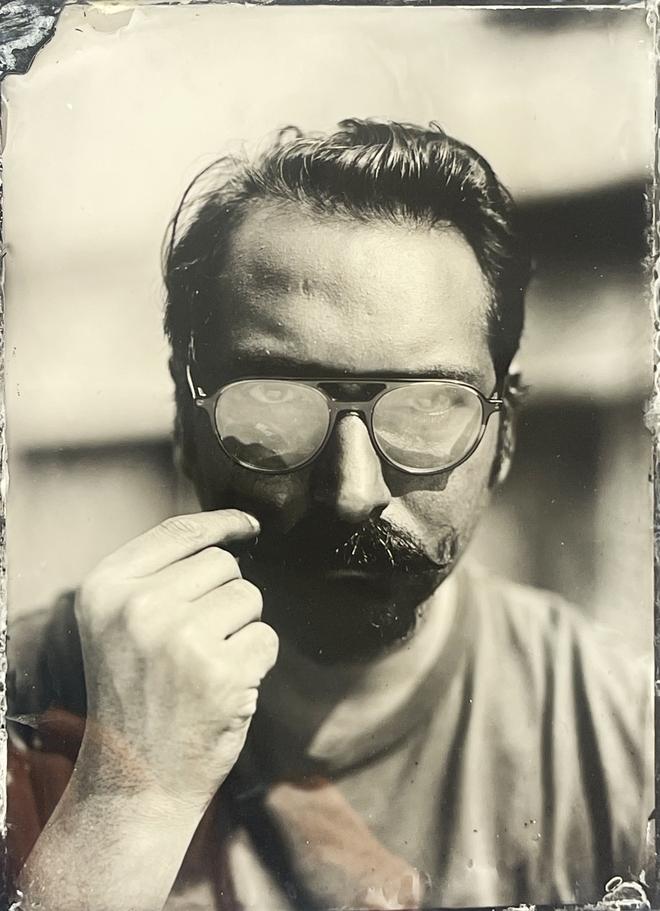

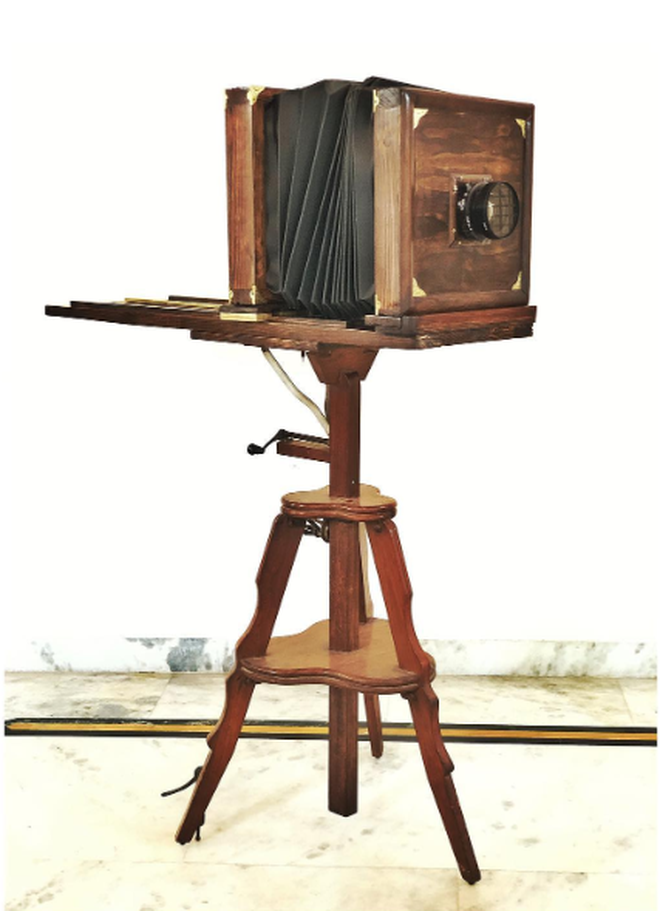

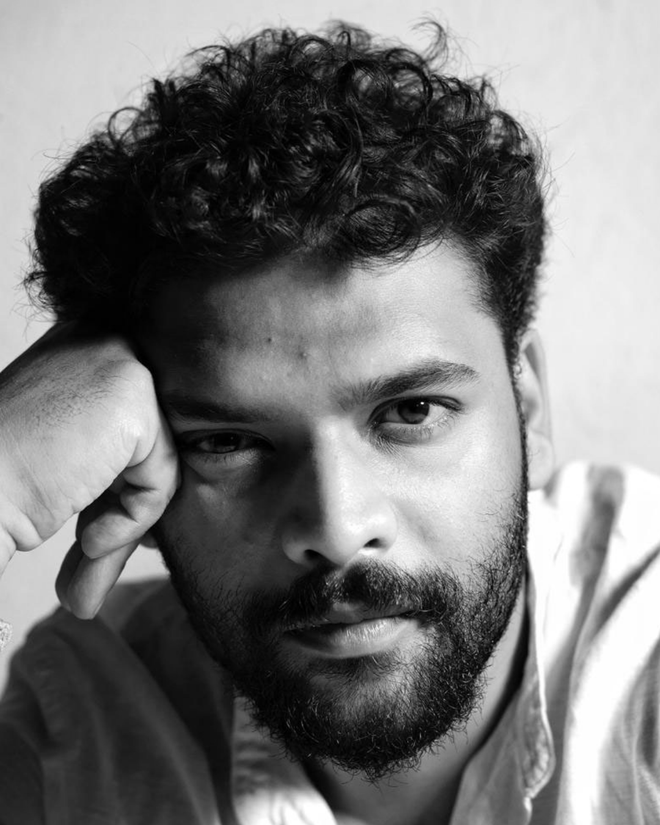

Another practitioner is Sarang Sena, 37. In early 2018, the Delhi-based visual artist decided to use the wet plate collodion (a 19th century process) for a personal project. He spent the good part of a year fine-tuning the chemistry for Indian weather. Then came the pandemic and a broken enlarger, which gave him one last step to complete: create his own enlarger. Once he had done that, he realised he could make his own large format view camera — big wooden boxes with bellows on a stand that most of us had last seen in movies from the 1940s and 50s.

The culmination was a series titled Six Feet Apart, where he created portraits of people who visited his house. “With a view camera, there’s a lot more interaction with the subject or the space, and a big thought process before you even set up the camera,” he says. Another of his portrait series, Contributors — celebrating a diverse set of individuals for their contribution to a COVID-hit society — made around the same time appeared in Vogue Italia. A key factor that drew Sena to this process was that each image was one-off, “there’s no way to repeat that particular image”.

He has since set up a studio space called Class of Yesterday: CYStudios in Delhi, where anybody can book their own unique portrait. Footballer Sunil Chhetri is a client, as are actors Dipannita Sharma and Nasir Abdullah.

MAP does its bit

Making the alternative accessible

There are a few photographers whose work I’ve been obsessed with for a long time: Sarah Moon, Paolo Roversi, Jack Davison, all of whom shoot fashion, though they are not just fashion photographers. Their images are the result of a combination of shooting and printing, the latter as important as the former. Moon uses direct carbon printing for her super saturated hues and is happy to degrade her negative; Roversi, who has possibly the largest stock of the now discontinued 8x10 Polaroid film, does platinum palladium prints; and Davison recently did a series of photogravure from his digital work.

As somebody who was wondering how to even attempt any of these methods, learning that they are, for the most part, accessible in India, feels liberating. Three touchstones have emerged to learn alternative processes in the country: Maze Collective Studio in Delhi, Studio Goppo in Santiniketan, and Studio Kanike in Bengaluru.

Maze Collective, co-founded by Ashish Sahoo, 34, and Zahra Yazdani in 2020, offers one-month alternative process residencies and shorter film photography workshops. Sahoo has also created one of India’s cheapest large format view cameras, essential to some alternative processes, with his collaborator Himanshu Bablani, who runs a makerspace called Banana House in Delhi. “You can get some really cheap cameras abroad, but by the time they come to India with customs duties and all, they become expensive. Plus, if any problem arises with the camera, we can troubleshoot and send you the parts,” he says, explaining that most parts are 3D printed and the rest are laser cut with stainless steel.

Santiniketan-based Arpan Mukherjee, 46, has been practising alternative processes the longest. He started in 2000-2001, not as a photographer but as an artist working with photosensitive materials in the form of silkscreen. “With alternate process, you can click an image, print it on your own, on leaves, on paper, on any surface,” he says. “And you have to print it with your hands. So the quality of the photography doesn’t depend on the camera, or the printer, but on your skill and craftsmanship.”

In 2015, the artist and associate professor in Santiniketan’s Department of Graphic Art, co-founded Studio Goppo with his partner Shreya to grow the alternative processes community. They offer two-week to two-month residencies to teach not only commonly known processes but also rarer ones such as calotype (where paper coated with silver chloride is exposed to light in a camera obscura) and colour gum bichromate (a process using salt of dichromate that produces painterly images).

Trying hybrid methods

Interestingly, alternative processes aren’t about shunning modern technology. All the practitioners work with contemporary technology when required, and in fact, use hybrid methods to create something new. “You can click an image on your digital camera, create and print a digital negative,” Mukherjee explains.

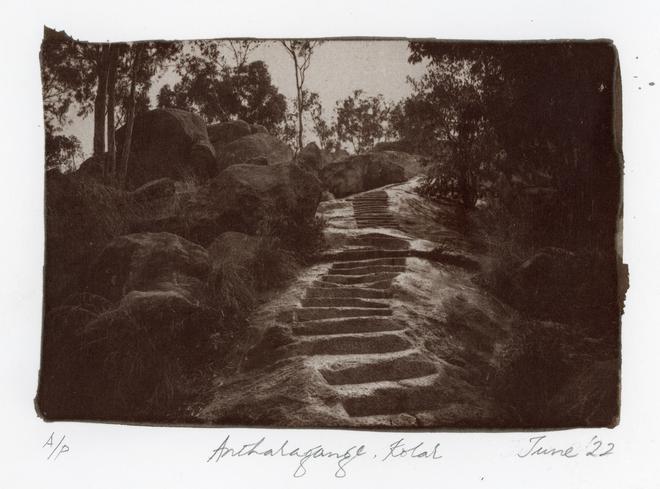

With such processes also come more layered ways of storytelling. Vivek Muthuramalingam, photographer, artist, and founder of Studio Kanike in Bengaluru, talks about elevating his documentary photography practice. For a series that he did on Goa’s poders (bakers) a few years ago, he used seawater from nearby beaches to create salt prints — and as he described in a personal essay in the Dark ‘N’ Light zine, the “organic substances that came along with the sea water, like plankton and algae, imparted its own tonality and hue to the print”.

Muthuramalingam explains the versatility of the process to me with another example: “For instance, if I were doing a work that follows the Silk Route, and I go to Cambay to find nothing there [in the Travels of Ibn Battuta, the scholar-traveller wrote an entire chapter on the city that was once an important trading centre in Gujarat], I could pick up salt and create the whole series.” The choices are endless: maybe cyanotype for a theme of loss steeped in blue or Van Dyke brown for sepia-tinted memories?

These processes are not just curiosities anymore; they have started to be woven into mainstream photography and art, textile design, and even magazines and online. And the trend isn’t showing any sign of slowing down.

Print perfect

The writer is a fashion consultant and commentator based in New Delhi.