Canada is currently grappling with a significant economic issue: market concentration. A select few corporations dominate key sectors, leading to reduced competition, rising prices and limited purchase options for consumers.

Canada’s grocery industry is a prime example of this. A recent report from the Competition Bureau found that a lack of competition in the grocery sector is resulting in higher food prices.

The grocery industry is dominated by five major players — Loblaws, Metro, Empire (the owner of Sobeys), Walmart and Costco. These five companies account for over three-quarters of all food sales in Canada.

The Bureau recommended four policies to encourage competition in the sector. These include establishing a grocery innovation strategy, encouraging new independent and international players, introducing legislation for consistent unit pricing and limiting property controls.

While independent grocery chains could be a viable alternative, they don’t occupy as large a presence of the market as they do in other countries. The Canadian grocery market is heavily concentrated and limits the ability of independent chains to compete by forcing them to purchase their products from larger chains.

History of monopolies

Canada’s economy has historically been marked by notable monopolies, thanks to its vast geographical expanse and relatively sparse population.

Entities like the Hudson’s Bay Company and Canadian Pacific Railway company played significant roles in the country’s development. This largely happened out of concern that domestic companies would be overwhelmed by American competitors unless they grew significantly.

Recent trends indicate this phenomenon is not only persisting, but intensifying. While Sobeys, Loblaws, Metro, Costco and Walmart dominate over 60 per cent of the grocery sector, Bell, Rogers and Telus command about 89 per cent of the wireless telecommunications market.

The concentration of power extends beyond these sectors. The banking industry in Canada is dominated by six banks — the Royal Bank of Canada, TD Bank, Scotiabank, the Bank of Montreal, CIBC and National Bank, which collectively control about 93 per cent of the industry.

Similarly, the beer market is largely controlled by two multinational giants, Anheuser-Busch InBev and Molson Coors.

And the Canadian telecommunications industry is still reeling from the recent merger between two of the industry’s giants, Rogers Communications and Shaw Communications. The implications of this deal are far-reaching.

The Rogers-Shaw merger

The Rogers-Shaw merger’s final approval came with 21 enforceable conditions Rogers and Videotron must adhere to, aimed at bolstering competition and reducing costs for customers.

The merger’s approval depended on Shaw selling its Freedom Mobile business to Quebecor’s Videotron. If Rogers breaches its conditions, it must pay up to $1 billion in damages. Videotron could be subject to $200 million in penalties if it fails to meet its commitments.

Despite these conditions, some remain skeptical about the impact of the merger on competition in Canada’s telecommunications sector.

Some critics have argued the merger may lead to higher prices for consumers and less innovation. Carleton University political economy professor Dwayne Winseck warned it could lead to a “tight oligopoly on steroids.”

On the flip side, other experts believe the merger could benefit consumers by accelerating the rollout of 5G networks and improving infrastructure and services, particularly in rural areas.

Read more: Here's how the Rogers-Shaw merger could benefit Canadian customers

However, these benefits could be offset by the potential for higher prices and less competition. The merger could lead to a dominant market share in Ontario, reducing competition and potentially leading to higher internet prices.

This is particularly concerning, given Ontario’s average monthly price of home internet services is already higher than the national average. This situation underscores the need for a revamp of Canada’s competition laws.

Loopholes in competition law

The merger has sparked controversy because it exploited weaknesses in Canada’s anti-monopoly law, the Competition Act, to push the deal through.

The Competition Act has been criticized for failing to prevent acquisitions that allow large firms to eliminate competitive threats and solidify their dominance.

As Canada’s competition watchdog, the Competition Bureau can review mergers to determine if they will be harmful to competition. But since its introduction in 1986, the bureau has only challenged 18 mergers and has never won a challenge on final judgment.

The law also has a high bar for intervention in a merger, often favouring negotiated agreements that include concessions or remedies that address some of the competition concerns, but not necessarily all.

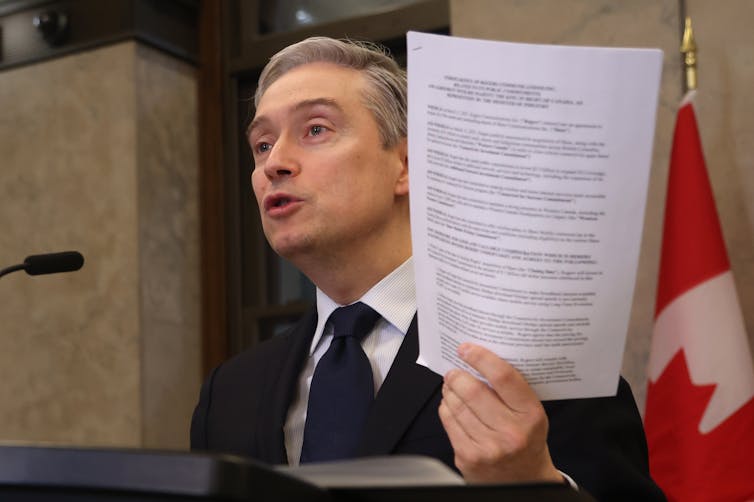

The Competition Commissioner, Matthew Boswell, believes the existing competition laws are inadequate. Boswell has been hamstrung by legal loopholes and unable to prevent anti-competitive mergers, like the Rogers-Shaw deal, from happening.

Challenges and opportunities

Along with rising consumer prices, limited purchase options and intensifying competition, the growth of monopolies in Canada has led to a host of other issues.

Monopolies have the potential to stifle innovation — a key driver of economic growth, as a lack of competition tends to dampen innovative efforts. Productivity growth, which is crucial for improving living standards, is also under threat, as monopolies can create an environment less conducive to efficiency and progress.

As Canada embarks on its post-pandemic economic recovery, policymakers must ensure economic resilience and inclusiveness while preventing existing monopoly issues from worsening.

At the same time, there is an opportunity to reshape the economic landscape to encourage competition and foster innovation, benefiting everyone involved in the market.

This journey towards a more prosperous future will require rigorous scrutiny of developments like the proposed Rogers-Shaw merger and the wisdom to navigate the interplay of monopolies, competition and the broader economy.

Garros Gong does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.