WASHINGTON — “Enough is enough.”

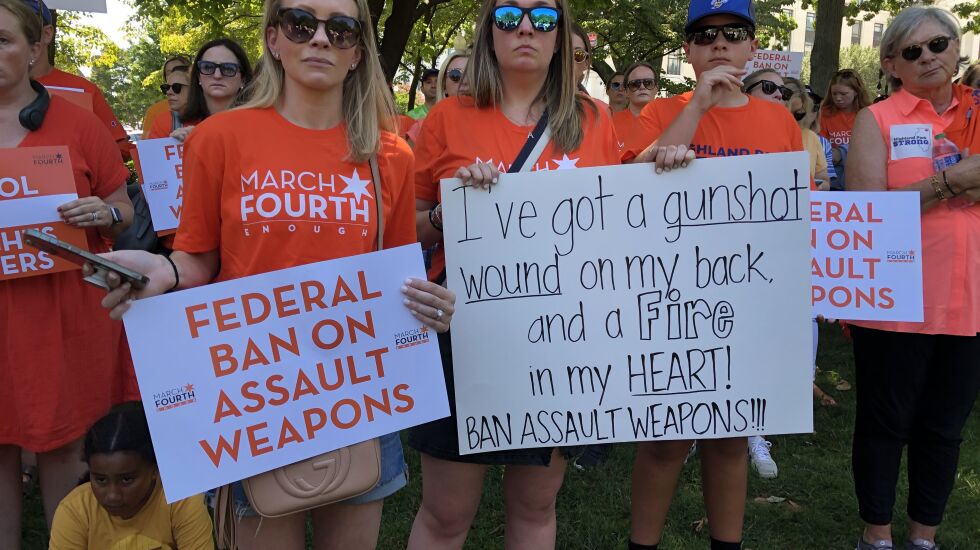

That was the chant Wednesday when a few hundred — many wearing orange T-shirts, most with connections to Highland Park or Uvalde — rallied and marched on Capitol Hill for a federal ban on assault weapons. Later, some went to the White House to huddle with staffers on their uphill mission.

Here’s the reality: Enough is not yet enough, when it comes to Congress passing a federal assault weapons ban. The Democratic House may be able this summer to pass something. But there are not 60 votes in the Senate, evenly split between Democrats and Republicans.

Let’s hand it to the organizers — they got this new group together — called “March Fourth” and helmed by Winnetka’s Kitty Brandtner — just days after the Highland Park July 4th parade massacre. They took care to include others — not just from Highland Park, especially from Uvalde — impacted by gun violence.

They raised money to help pay travel costs to D.C. for folks who may not have had the means to make the trip. They understood the issue about gun violence is not just about Highland Park, as horrific as it’s been for this suburb, marked by ravines and hugging the shores of Lake Michigan.

It’s about the totality of what is happening across the U.S. with insane access to weapons of war.

A shooter on a rooftop overlooking the Central Avenue parade route, prosecutors say, used a legally purchased assault weapon to kill seven people, wound dozens and traumatize untold numbers of others.

It’s just weeks after two May massacres, where gunmen using legal assault weapons murdered 10 people in a Buffalo, New York, supermarket and slaughtered 21 in a Uvalde, Texas, elementary school.

And it’s Wednesday, in a week, in a month, in a year where Chicago continues its struggles with chronic, deadly gun violence resulting in shootings and deaths.

After Uvalde and Buffalo, Congress passed and President Joe Biden signed into law on June 25 the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act, the first gun control measure in almost three decades. On Monday, Biden, wearing a Highland Park Strong orange ribbon, presided over a big South Lawn gathering in what was called a “celebration” to mark the historic passage of the new law that only served to highlight the lack of an assault weapons ban.

**** ****

The rally is on a park-like site near the Capitol. In the course of the event, survivors and victims will speak as well as members of Congress, all Democrats. From Illinois, that’s Sen. Tammy Duckworth, Reps. Brad Schneider, Jan Schakowsky and Sean Casten, plus Sen. Chris Murphy from Connecticut. Kina Collins, the anti-gun activist from Chicago’s West Side — who just lost her primary bid for Congress — also spoke.

Abby Brosio, 34, is telling her story.

“I am here today to make you all uncomfortable,” she said. Her orange T-shirt covers the gun wound on her left side, near her back.

She is a mother of a 3-year-old son and a year-old daughter. She is a science teacher at the Hannah Beardsley Middle School in Crystal Lake, and she would tell me later she is here also fighting for her students.

Her husband, Tony, is the manager of Gearhead Outfitters, on Central and Second, where she came with her family to view the parade. That corner was at the epicenter of the attack.

Here’s what she said she saw:

“My eyes fixated on the roof of the building adjacent to my husband’s store. There, crouched with a large gun,” she said, and paused, “was a figure with long hair, a shooter. I thought, a woman? I thought to myself, no, a woman is not shooting at us. This is a dream.”

She screamed to the crowd there was a shooter and ran into the store with her baby in her arms as a bullet grazed her side.

Brosio said she was interviewed by police afterward, “being one of the only witnesses that saw the shooter.”

We know now that the accused gunman, Robert Crimo III, allegedly dressed like a woman to meld into the crowd to escape as people fled the parade.

“This should not be political,” Brosio said. “I am done being complacent and desensitized. I am certainly sick of everyone’s empty thoughts and prayers with no actions to back them up. Action is what is needed now.”

In June, Congress acted. But let’s not pretend here. Solutions to gun violence — especially with assault weapons — have to deal with access to weapons of war.

Lexi Rubio, the daughter of another speaker, Kimberly Rubio, was killed at Uvalde’s Robb Elementary School. Kimberly Rubio talked about the day her child was murdered. She posed what she called “one question” for Congress to consider.

Said Rubio, “What if the gunman never had access to an assault weapon?”

Enough said. But not enough done. Not yet.