Millions of Australians have had their privacy breached in recent cyber attacks against Optus, Medibank and other companies.

Cybercriminals stole sensitive health and financial data that can be used for ransom, blackmail or fraud.

Read more: Why are there so many data breaches? A growing industry of criminals is brokering in stolen data

Law enforcement agencies are still investigating the origin of these attacks, but as experts in cyber and national security we can say two things are already clear.

First, anyone affected should check their credit record. Second, Australia’s international cyber engagement strategy – which sets the terms for how we work with other countries to maintain national cybersecurity – is desperately in need of an update.

How to turn data into credit

Cybercrime is most often motivated by making money, as the return on investment can be enormous. One recent estimate suggested a low-end attack costing US$34 could bring in US$25,000, while spending a few thousand dollars on a more sophisticated attack could bring in up to US$1 million.

Hackers might demand a ransom in return for the stolen information. Failing that, they can make money from it in other ways.

In the September Optus attack, for example, data including names, birth dates, email addresses, driver’s licence numbers, and Medicare and passport details were taken.

Read more: Optus data breach: regulatory changes announced, but legislative reform still needed

One quick way to turn these data into money is to use them to apply for credit cards. Many credit card providers, eager for new customers, have very simple and streamlined processes to check identity.

Alongside stolen data such as a name, address and driver’s licence details, cybercriminals will need an email address, a phone number and payslips.

Phone numbers and email addresses used for communication and authentication are easy enough to provide, and fake payslips can be generated using free websites.

In some cases, cyber criminals can start using the credit cards instantly if approved. The victim will have no idea about the existence of this credit card unless the credit report is checked as part of a subsequent mortgage or credit application.

How to track cybercriminals

Cybercriminals naturally take steps to remain anonymous. However, applying for a credit card does leave traces that can be used to track them down in the following ways:

- the phone number used for the credit card application can be tracked, with a court order and the help of the telecommunication service provider

activity on the credit card obtained with the stolen data can also be tracked, as can email correspondence, with the help of the credit card provider

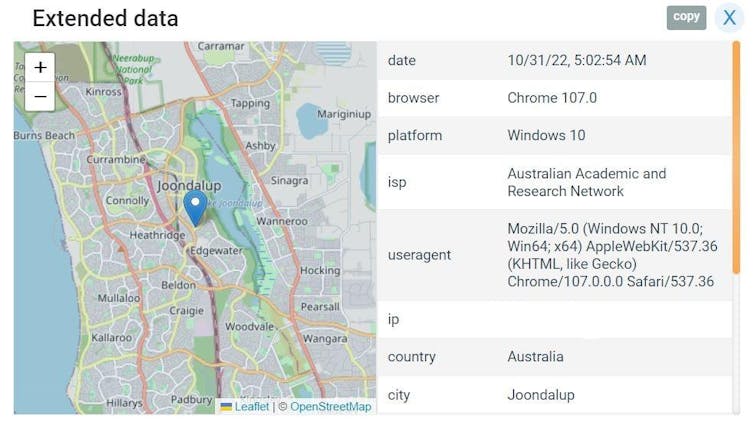

any suspicious IP address associated with the credit card can lead to further intelligence on the cybercriminals, and the internet service providers (ISPs) or virtual private network (VPN) providers may assist in tracking down the criminals.

A national security issue

The Optus and Medibank hacks have caused significant problems for individuals. They have had to apply for new identity documents, and the final costs are likely to total hundreds of millions of dollars.

But preventing cyber attacks can also be a matter of national security, as a recent ransomware attack on an Australian Defence Force contractor has shown.

The data affected in such attacks may easily extend beyond identity theft to include data relevant to national defence, business and society. The risk of these attacks has been recognised in Australia’s cyber security strategy, but more must be done to prevent them.

Stronger rules for data protection

National cyber defence requires a “whole of government” approach, but it needs to go further. The commercial and civilian sectors must be included as well.

Private companies store huge amounts of private data. What they store and how they store it needs to be much better regulated.

The Optus hack, for example, revealed the company was keeping data not only from current customers but also past customers. Given how often customers change telecom providers, practices like this can lead to companies storing huge amounts of unnecessary personal data.

Current penalties for failing to protect customer data are also inadequate. At present, fines of up to A$2.2 million are the only enforceable safeguards available.

These penalties are too small to act as an effective deterrent, and they apply only after a breach has occurred. What we need are strict and enforceable rules regarding the storage of current consumer data and the deletion of past customer data.

Without new regulations, we will continue to see sophisticated cyber attacks targeting the private sector.

Borderless cybercrime

In many cases the cybercriminals are from other countries, which means we need international co-operation to track them down. This is when Australia’s International Cyber Engagement Strategy comes into play.

The strategy, published in 2017, aims to foster increased international attention to cyber threats. It calls for greater co-operation in the region and beyond to mitigate cyber risks.

Australia’s international cyber engagement is distinct from domestic cyber security efforts, which are undertaken under the auspices of the Australian Cyber Security Centre.

Cyber attacks of foreign origin are on the rise as a result of current international tensions. The current strategy may no longer be sufficient to address the international nature of cyber threats.

The strategy contains high-level promises of collaboration around strategic interests, but this is only a beginning. To create a comprehensive international cyber defence approach, we will need more detailed working arrangements with overseas partners.

Sascha-Dominik (Dov) Bachmann received funding from the Australian Department of Defence for research regarding grey zone and information operations targeting Australia.

Mohiuddin Ahmed does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.