Japanese writer Haruki Murakami has won phenomenal worldwide popularity. His Norwegian Wood, marketed as ren’ai shōsetsu (a romance novel) when it was first published in Japan in 1987, has become a veritable bible of love among young people in East Asia. English translations of Kafka On the Shore and 1Q84 have become New York Times bestsellers.

With his surreal or magical realist settings and references to western culture – popular music, whisky, anglophone classics such as The Catcher in the Rye and The Great Gatsby – Murakami is a most “un-Japanese” Japanese writer. He is often criticised, especially in his home country, for his deviation from Japanese literary tradition and his at times studied detachment from reality.

On this last point, one could say that his protagonists’ strong sense of isolation within surreal dreamscapes resonates with his experience as an author in Japan.

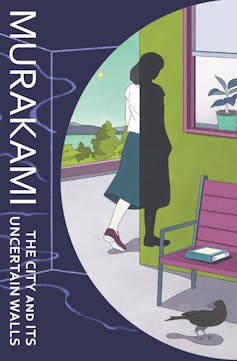

Review: The City and Its Uncertain Walls – Haruki Murakami (Harvill Secker)

Murakami’s latest novel The City and Its Uncertain Walls was published in Japan in April 2023. It reprises some familiar features. References to jazz, the Beatles’ Yellow Submarine, and Gabriel García Márquez’s magical realist novel Love in the Time of Cholera will all prompt recognition among Murakami’s global readership.

The novel’s combination of real and fantastical elements could not be more baffling – something Murakami’s fans have come to expect. The City and Its Uncertain Walls is easy to read, but readers must often forego comprehension. It features a walled town with no music or books, a speaking shadow, the ghost of a head librarian, and a teenage boy who remembers every book he has read.

Indeed, Murakami confessed in an interview with literary academic Rebecca Suter that he has “always wanted to write novels that are extremely readable and highly incomprehensible”.

In his afterword to the novel (a rarity for this author), Murakami recalls how he was not content with his early novella The City, and Its Uncertain Walls, which he published in the prestigious Japanese literary magazine Bungakukai (Realm of Literature) in 1980. He thought the work had something important to say, but the then 31-year-old writer felt he lacked the skill to express what that something was.

This bothered him – like a “small fish bone caught in my throat” – until, after a 40-year career as a writer, he finally felt he could rewrite and transform the novella into this new three-part novel.

The side of the egg

To understand the urgency behind Murakami’s decision to bring his fictional creation up to date, it is worth revisiting his acceptance speech for the Jerusalem Prize in 2009. In the speech, he expressed a commitment to supporting fragile humanity against oppressive and brutal systems of social control.

“Between a high, solid wall and an egg that breaks against it,” he said, addressing an audience in Israel, “I will always stand on the side of the egg.”

This was just after the Gaza War of 2008-2009, in which more than 1,000 civilians died.

Murakami’s wall-versus-egg metaphor cannot be taken as a simple binary. He went on to explain human beings are also the creators of the walls that make up the systems that separate and make enemies of people. This divisive process, he stated, “takes on a life of its own, and then it begins to kill us and cause us to kill others – coldly, efficiently, systematically.”

Clearly, Murakami questions the barriers that divide and harm our social existence. But how can this “professional spinner of lies”, as he calls himself, address serious real-world issues when his storytelling is marked by the recurrence of mysterious “uncertain” walls, shadows detached from people, monitory ghosts and other fantastical features?

In The City and Its Uncertain Walls, barriers are not indestructibly solid but more nuanced, elusive. Uncertainty is a feature of the narrative right from the beginning. The story of the walled city is told by a 15-year-old girl the young narrator meets at the award ceremony for an essay contest. The real girl lives in that city behind the wall, she claims, and the one that lives in this world is merely her shadow.

They fall in love and yet, divided from her real self, the girl promptly vanishes. What remains and becomes more real for the narrator as the years pass is her story of the walled city.

Years later, the now middle-aged narrator enters the city. In order to do so, he has to have his eyes wounded and his shadow taken by the Gatekeeper. This qualifies him to participate in the main activity in the town library – a library with no books. This consists of “listening” to “old dreams”. He is aided in this task by the girl, who is still 15, as there is no passage of time inside the city walls.

This interest in attending closely to past dreams evokes the profound origins of storytelling. The narrator repeatedly reminds us that the story of the city and the wall has been told to him by his girlfriend. Listening to the old dreams together, they “create and share a special, secret world”, a world that is none other than “a strange town surrounded by a high wall”.

Murakami has not made it easy for readers to gather a plain and direct meaning from his walled city. It seems, at times, to be an idyllic place where people live in deathless peace. At other times, it seems to be an ominous and coercive place that denies residents full reality. This is because their shadows, which entail their memories and souls, are forcefully taken from them and left to die outside the walls.

And yet to grasp of the nature of what imprisons them, people seem to need their shadows. This becomes clear when the narrator’s shadow comes to understand the intrinsic weakness of the wall, recognising it as artificially created – a story, in essence – and thereby mere illusion.

Both the city and the walls are established, experienced and perpetuated through the acts of telling and hearing. And understanding this is the way the confining walls, and perhaps other confining walls, may finally be overcome. To break through the illusion, the shadow urges the narrator, he must rid himself of doubt and trust his own heart: “If you don’t believe what it says, and aren’t afraid, the wall doesn’t exist.”

Mysteriously, the narrator finds himself and his shadow back in the real world. He becomes head librarian in a small town surrounded by mountains in Fukushima Prefecture. Mention of Fukushima is by no means arbitrary – it recalls the nuclear accident there following the Great East Japan Earthquake on March 11, 2011. On this day, for people affected, ordinary reality became disastrously surreal.

Reality becomes ambiguous in the Fukushima library too, as the narrator meets and has conversations with a figure who turns out to be the ghost of the former head librarian. It is to the ghost, rather than a living person, that the narrator tells his story of the walled city, as if the spectre is the only appropriate conduit to pass on the truths of walls such as these.

Ceaseless change and movement

Literary scholar Sofia Ahlberg has written recently about the transformative potential of stories that ask readers to enter magical worlds. She notes that stories with magical elements empower readers to consider possibilities for themselves and the world that might otherwise be seen as irrational. This can build confidence and resilience, especially in young readers facing an uncertain future.

Significantly, the teenage boy in Murakami’s story, who has total recall of every book he reads, overhears the narrator speaking to the ghost about the walled city. Alienated from his surroundings, the boy resolves to venture into the city and take up dream reading.

The City and Its Uncertain Walls is a tribute to storytelling and storytellers, both ancient and contemporary. It is also an urgent reminder of the porous and artificial nature of the walls we set up to divide us from the world and each other – walls that can be called into question by listening attentively to our shadow sides.

At the heart of what seems incomprehensible in this novel is Murakami’s belief that there is no single unchanging truth. In the afterword, he explains:

Truth is not found in fixed stillness, but in ceaseless change and movement. Isn’t this the quintessential core of what stories are all about?

His remark certainly applies to The City and Its Uncertain Walls. Rather than confinement behind rigid barriers, storytelling like this frees the reader’s imagination to occupy both sides of these ever-changing walls. And this freedom can strengthen the tolerance for opposed views, allowing people to consider multiple possible truths in our uncertain times.

Jindan Ni does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.