Along Chicago’s north lakefront near Rogers Park, there’s a couple of strange looking exercise stations with gravity workout machines, pull-up bars, benches — they look like a mix of a playground and gym. On a recent sunny afternoon, three kids and their grandmother were playing there.

“I have absolutely no idea [what I’m doing], but according to this I’m working out my upper body and I’m stretching at the leg lift station,” said 12-year-old Britain Konczal, who smiled ear-to-ear as she swung back and forth on a workout machine.

New to the area, their grandmother Regina Doresette is surprised to learn how this exercise station got here — by community members pitching it, working with the city to design it, and then essentially campaigning for it in a public, ward-level election through an annual process called participatory budgeting.

Participatory budgeting, in which residents get a direct vote in how tax dollars are spent, has been around in Chicago for more than a decade, and made its U.S. debut here in the North Side’s 49th ward in 2009, led by then-Ald. Joe Moore.

Chicago residents vote on how to spend the majority of the $1.5 million in “menu money” City Council members are allotted for infrastructure projects each year — in the wards that choose to use it. It’s also utilized in a handful of Chicago Public Schools as a form of civic education.

But participatory budgeting, or PB, has failed to launch here on the scale advocates envision, lagging other U.S. cities such as New York and Boston that have implemented citywide programs. Now, proponents of participatory budgeting see an opportunity with Chicago’s newly elected mayor, who has vowed collaboration with residents, and whose transition report calls for Chicago to be “real pioneer” in participatory democracy.

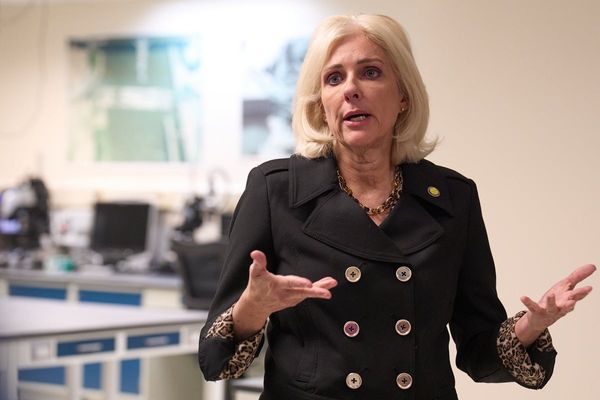

“This will be the third mayoral administration that [we’ve] approached to talk about citywide PB,” said Ald. Maria Hadden, 49th Ward, who before being elected, helped start the non-profit Participatory Budgeting Project that aimed to spread the concept.

Those who work on participatory budgeting see it as a way to solve a pertinent threat to democracy: the disconnect and distrust between elected officials and those they represent.

“That’s what we’re seeing: like real disillusionment with the idea of democracy, if we only practice it through elections,” said Josh Lerner, executive director of the group People Powered, which aims to broaden the understanding of democracy beyond elections.

“If people see a big, money-driven electoral system as the only way we can have democracy, the natural response to that is to not want democracy. And that leads to authoritarianism.”

Engaging the public

Each year, the city of Chicago passes a massive, multi-billion-dollar budget that is difficult for even the Council members who vote on it to wrap their minds around.

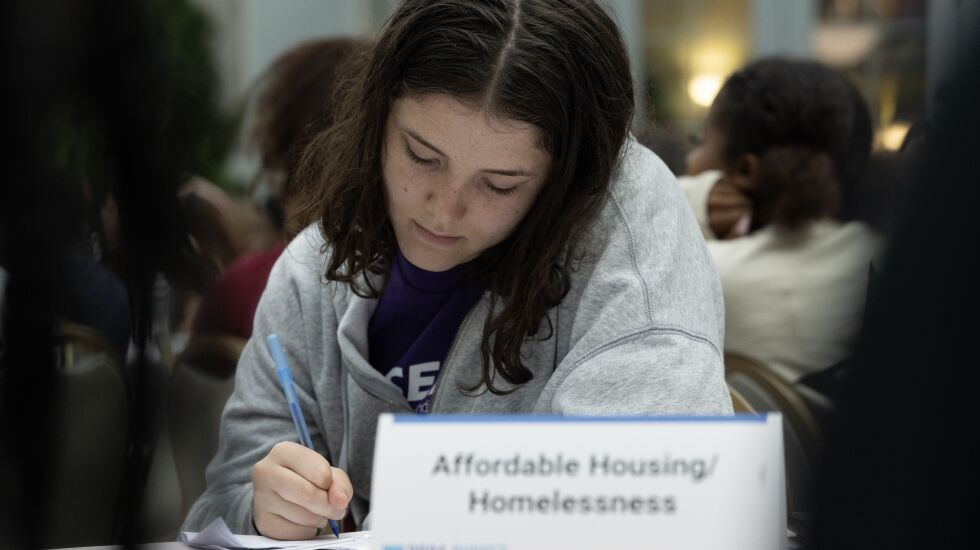

To try to engage more residents, former Mayor Lori Lightfoot partnered with the University of Illinois at Chicago Great Cities Institute to hold public input sessions. Mayor Brandon Johnson is continuing that effort, having just wrapped up a similar series of roundtable discussions.

Thea Crum, an associate director at Great Cities, which facilitates the engagement process for the city, said there’s nothing quite like participatory budgeting, though, to connect with residents.

“People who participate talk about how they learn more about what their needs are in their community, that they meet more neighbors … they learn more about how government works, they’re more comfortable contacting government agencies and officials,” said Crum.

Crum points to recent projects: a group of parents pushing to make their playground accessible for kids with disabilities; close friends of a teen who died crossing train tracks to avoid a dirty, dimly lit underpass banding together to clean that underpass; students pushing for a new water fountain in a lead-ridden school.

These ideas come from residents and city engineers and department employees help make them a reality.

“They’re in the process of co-creation with their government. … And so that is a direct way where the government is saying, ‘I heard you, and now I’m directly impacting and directly building what we have co-created together,’ ” Crum said.

Possibilities, and limits, of community budgeting

In the 49th Ward on a recent weeknight, a community engagement director, Jeff Gonzalez, welcomes several participants to a virtual information session. His goal is to very directly define what can, and cannot, be funded through participatory budgeting.

“The menu funds that we have can only be spent on capital projects,” Gonzalez told participants. “They have to be low-maintenance, we can’t pay for any staffing for projects.”

But Lerner, with People Powered, said if the goal is to reshape how people view their government, and strengthen democratic processes, there has to be real money on the table for meaningful projects — beyond capital improvements.

In Paris, France, for instance, the city-led participatory budgeting process funnels €100 million into community projects each year, with 10% of Paris residents voting on projects, compared to 1% in Chicago. Those projects can include programmatic ideas such as violence prevention services and infrastructure projects such as solar panels.

In the 49th Ward, Hadden recalled taking part in PB as a ward resident, when she and fellow first-time condo owners wanted to improve their half-finished building.

“For me it was like, ‘Oh I have no power over here, here’s something tangible and local that makes me feel empowered, and I can feel real results in my community,’” Hadden recalled.

Now, she’ll use her seat as an alderperson to push for an expanded, citywide process that focuses on Chicago’s youth, Hadden said. It’s something she thinks could appeal to the city’s new mayor.

In a statement, a spokesperson for Johnson says the mayor’s office will explore ways to introduce aspects of participatory budgeting into the overall budget process.

Mariah Woelfel covers Chicago city government and politics for WBEZ.

This story is part of “The Democracy Solutions Project,” a partnership among WBEZ, the Chicago Sun-Times and the University of Chicago’s Center for Effective Government. Together, we’re examining critical issues facing our democracy in the run-up to the 2024 elections.