Georgia Meloni, leader of Italy’s post-fascist party Fratelli d'Italia, became prime minister last September, and she wasted little time in setting the new government’s tone on immigration. On November 4, the country closed its ports to rescue ships, blocking more than a thousand migrants, and since then Meloni’s stance hasn’t softened.

Italy is at the crossroads of the Balkan and Mediterranean migration routes, and during the immigration crisis of the 2010s, it was one of the main gateways to Europe. From 2014 to 2016, between 170,000 and 180,000 migrants disembarked each year on the island and southern coasts, often in dramatic conditions. During this period, the country’s far-right parties and populist politicians, in particular Matteo Salvini of the Lega Nord (Northern League), rose in prominence. In 2018 and 2019, Salvini served as minister of the interior as well as holding other positions, he never hesitated to express brazenly xenophobic positions.

The number of foreigners in Italy has since stabilised to around 5 million, or 8.5% of the population. Despite the sharp reduction, anti-immigrant acts still take place. In Italy, a discourse linking illegal immigration, insecurity and crime is projected against the backdrop of the myth of the invasion. Upon opening the National Museum of Italian Emigration in Rome in 2009, then president and the former leader of the Communist party told the crowd to “[not] forget that we were emigrants”. His words appear to have had little impact on the government’s harsh position toward new arrivals today.

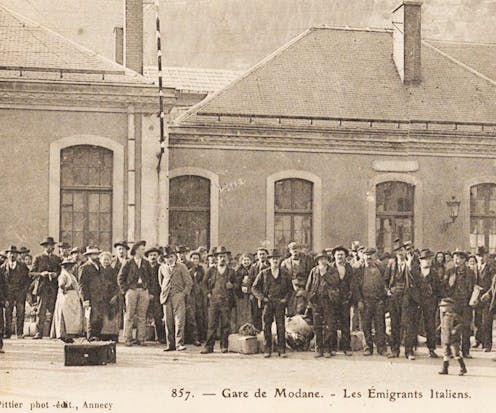

26 million Italian emigrants in a century

It’s crucial to remember that before being a country of immigration, Italy was first and foremost a country of emigration: around 26 or 27 million Italians left their country between the 1870s and 1970s] to spread out across all continents. Contrary to what the collective memory would have us believe, these Italian migrants were not always well received, regardless of their destination.

In France, the Italian community accounted for the bulk of immigrants between the early 20th century and the 1960s. Yet our memories of the diaspora have become rose-tainted in the wake of later, extra-European and post-colonial migratory movements, whose “otherness” appears more marked and threatening. History is there to remind us that Italians’ lives as migrants was not any easier.

The French imagination has long brimmed with condescending representations and stereotypes of Italy, as evinced by the country’s 18th and 19th century travel literature. Italians’ nicknames are a prime example of this. One of the most common was “macaroni”, which refers to the contempt in which the French hold the eating habits and frugality of their transalpine neighbours.

The two countries’ official relations also impacted how French people related to newly arrived Italians. While it would seem the cultural proximity of two “Latin sisters” might allow Italians to integrate well, tensions occasionally boiled over. After Tunisia became a “protectorate” of France in 1881, crowds waiting at Marseille’s Vieux Port for returning French soldiers thought they heard whistles coming from the nearby headquarters of an Italian society. The incident was used a pretext for attacking Italians over the following days, and three people lost their lives, including two Frenchmen, while 21 were injured, including 15 Italians. This violent episode became to be known as the “Vespers of Marseilles”, a reference to the 1282 massacre of the French in Sicily known as the “Sicilian Vespers”.

Similar incidents took place in the rest of the country, with brawls breaking out in Paris, Vitry-sur-Seine, Choisy-le-Roi and Nancy. And Italy’s joining the Triple Alliance with Germany and Austria-Hungary the following year did not help matters.

The Italian emigrants responded to the need for labour

Adding fuel to the flame was French people’s view of the diaspora as “unfair competition”. Responding to an urgent demand for labour in France, Italians did not shy away from the least-paid and toughest jobs. Of course, bosses saw profit in this, whereas, the working classes, notwithstanding some gestures of solidarity during strikes, grew increasingly xenophobic against a backdrop of worsening economic crisis at the end of the century. Tensions culminated in August 1893, in a “massacre” at the Aigues-Mortes salt works, which left three dead and dozens injured.

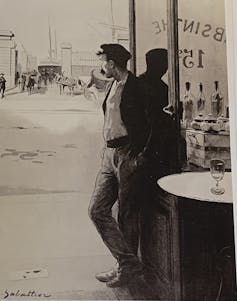

Amid political tensions, economic and demographic decline, the feeling that Italians were “invading” France took hold. To many, the Italian character was intrinsically violent, its morals, primitive and savage. The figure of the “knife-wielding” Italian was regularly splashed across the press, feeding the French public’s view of the diaspora as a threat to societal order. They were portrayed as gamblers, drinkers, assiduous clients of prostitutes, overly exuberant, excessively talkative and noisy

Even their shared religious practice did not find favour. Italians’ piety, characterised by a frequent display of crosses and public processions, was stigmatised. In fact, such behaviour outraged the laity, with the expression “Christos” spouted as an insult in Marseille. Nor did it impress the French Catholics, for whom the Italian faith remained superficial and based on primitive superstitions.

Although it would become less violent, Italophobia did not disappear after the First World War. The confrontation between Fascists and anti-Fascists, even though it involved only a small minority (less than 10%), would go on to provide new focal point for discrimination: depending on their political leanings, the French found a threatening Italian figure to point to. The economic crisis in the 1930s also reactivated xenophobic discourse and led to new protectionist measures in the labour market.

It was not until the migratory flow dried up in the early 1960s that Italians became “invisible” in the public eye. In time, they enjoyed a positive image again. At first a pejorative nickname, the name “Ritals” was taken up as a kind of memorial emblem by the descendants of migrants in a context of revaluation and attractiveness of the country of origin.

Recurrent Italophobia did not erase all traces of Italianness. These are mainly expressed on a cultural level and, contrary to the fears often expressed, they do not constitute a threat to the supposed integrity of the national identity but enrich French culture. This is a lesson from history that is probably not sufficiently mulled over on both sides of the Alps.

Membre du Conseil d'orientation du musée national de l'histoire de l'immigration (Paris)

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.