NASA’s Juno spacecraft at Jupiter this week got to within 645 miles/1,000 kilometers of Ganymede, the Solar System’s largest moon.

The spacecraft’s JunoCam imaging system had just 25 minutes to take photographs, just long enough for five exposures, before it then got close to Jupiter for the 33rd time.

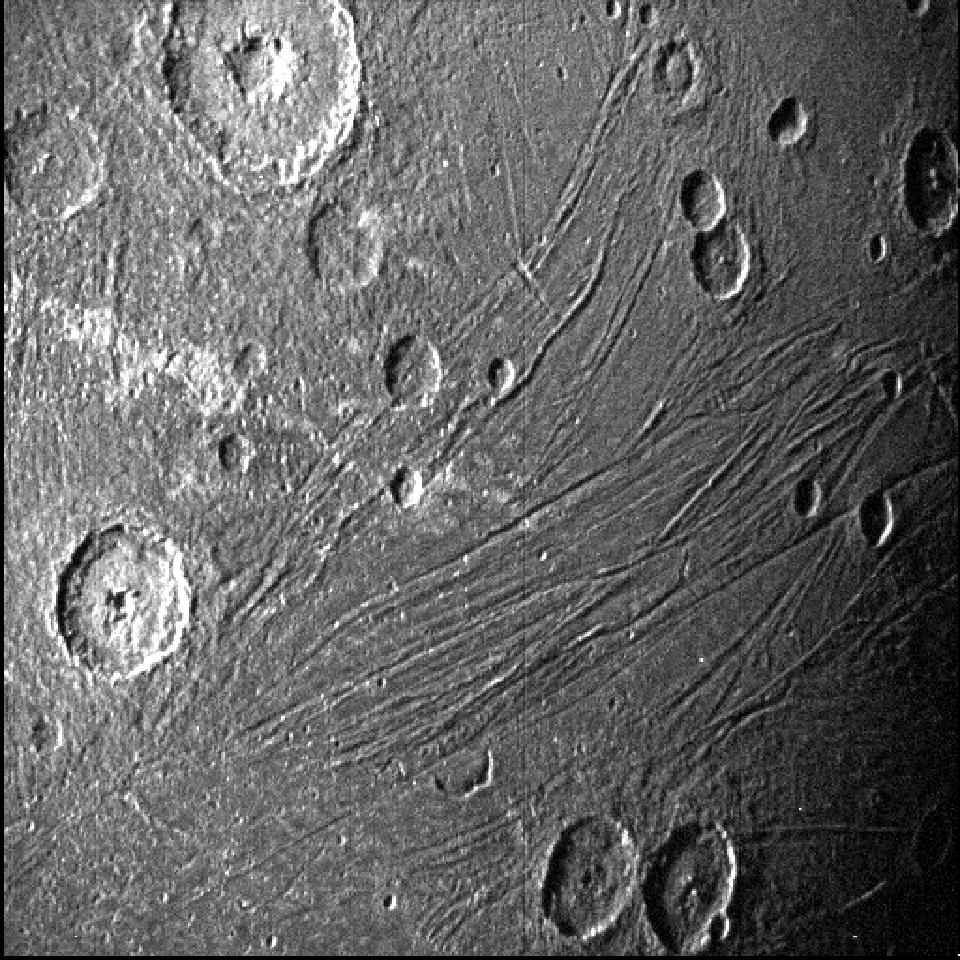

Bigger than Mercury and only slightly smaller than Mars, images are now coming back from Juno of Ganymede’s pock-marked, gorgeously grooved and patterned surface.

The Juno science team will now scour the images, comparing them to those from previous missions, looking for changes in surface features that might have occurred in the 20 years since Ganymede was last photographed.

“Things usually happen pretty quick in the world of flybys ... every second counts,” said Juno Mission Manager Matt Johnson of JPL. On Monday, Juno raced past Ganymede at 12 miles/19 kilometers per second and on Tuesday it skimmed the cloud tops of Jupiter at 36 miles/58 kilometers per second.

Larger than both Mercury and Pluto and only a third smaller than Mars, Ganymede has a diameter of 3,273 miles/5,268 kilometers. It’s the largest moon and the ninth-largest object in the Solar System.

The biggest of Jupiter’s 79 moons, Ganymede is one of the four Galilean satellites, the other being Europa, Callisto and Io. These icy Jovian moons were first discovered by Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei in 1610.

Could Ganymede support life? It does have a thin oxygen atmosphere, but it’s not breathable. However, single-cell microbial life could exist in its subterranean ocean.

About 10 times deeper than Earth’s oceans and thought to contain more water than is found on Earth, Ganymede’s ocean is reckoned to be 60 miles/100 kilometers thick and buried under an icy crust about 95 miles/150 kilometers thick.

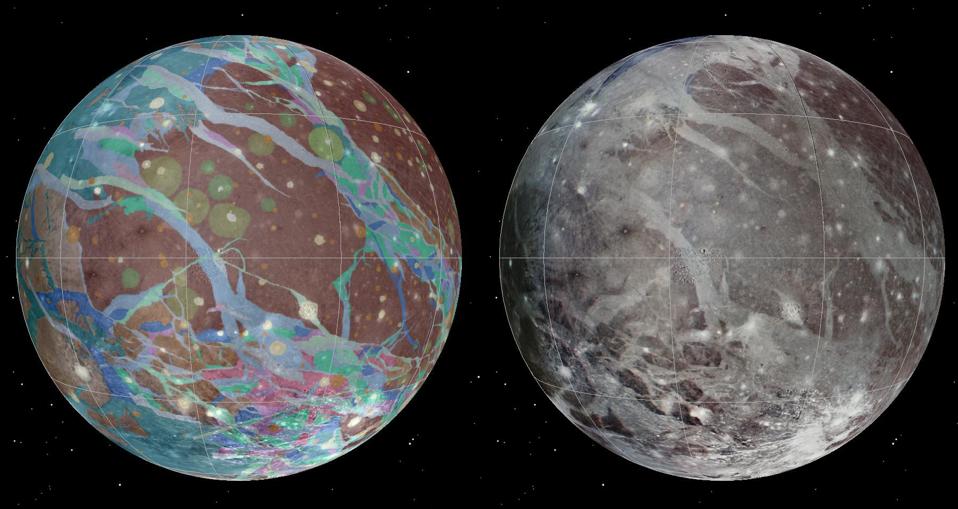

“Ganymede’s ice shell has some light and dark regions, suggesting that some areas may be pure ice while other areas contain dirty ice,” said Juno Principal Investigator Scott Bolton of the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio. “MWR will provide the first in-depth investigation of how the composition and structure of the ice varies with depth, leading to a better understanding of how the ice shell forms and the ongoing processes that resurface the ice over time.”

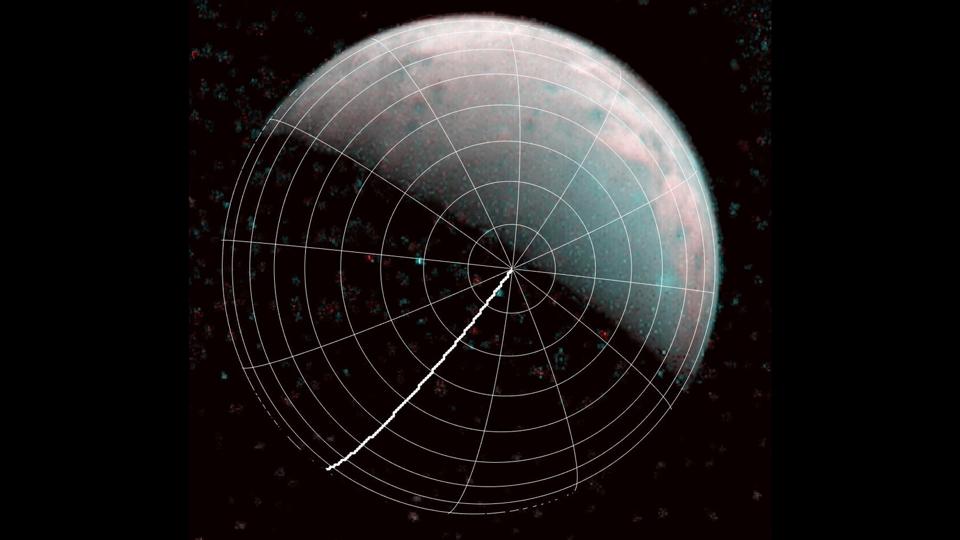

Ganymede is also the only moon in the Solar System with a magnetic field—a bubble-shaped region of charged particles. Scientists have spotted aurorae—as ribbons of glowing, hot electrified gas—around its poles.

It’s the movement of the aurorae—which rock back and forth as Ganymede’s magnetic field interacts with nearby Jupiter’s—that enabled scientists to determine that a large amount of saltwater exists beneath Ganymede’s crust.

“As Juno passes behind Ganymede, radio signals will pass through Ganymede’s ionosphere, causing small changes in the frequency that should be picked up by two antennas at the Deep Space Network’s Canberra complex in Australia,” said Dustin Buccino, a signal analysis engineer for the Juno mission at JPL. “If we can measure this change, we might be able to understand the connection between Ganymede’s ionosphere, its intrinsic magnetic field, and Jupiter’s magnetosphere.”

Previously photographed by NASA’s Pioneer 10, Voyager, Galileo and the passing New Horizons spacecraft, Juno’s images reveal a two types of terrain on Ganymede—highly cratered, darker regions and lighter terrain that’s grooved and patterned.

Along with the Ultraviolet Spectrograph (UVS) and Jovian Infrared Auroral Mapper (JIRAM) instruments, Juno’s Microwave Radiometer’s (MWR) peered into Ganymede’s water-ice crust, obtaining data on its composition and temperature.

Juno already had a brief look at Ganymede, returning the first-ever images of its north pole after a flyby on December 26, 2019. However, this week’s flyby is by far its closest examination of the giant moon.

Having just completed its core five-year mission surveying the giant planet, Juno’s 34 perijove—close flyby—of Jupiter sees it in a new, shorter orbit of the giant planet. Its new trajectory has been carefully planned to make sure that Juno gets close to two other moons of Jupiter during its remaining 42 orbits through 2025.

The furthest solar-powered spacecraft from Earth, Juno will get to within 200 miles/320 kilometers of Europa on September 29, 2022 and then flyby the volcanic moon of Io twice, getting to within 900 miles/1,500 km of it on both December 30, 2023 and on February 3, 2024.

It’s possible that there will be a further mission extension after that if the spacecraft and its battery remain healthy, though ultimately it will perform a “death dive” into Jupiter to prevent it accidentally crashing into—and polluting—one of Jupiter’s moons., all of which are on NASA’s to-do list in its search for traces of life.

“Juno carries a suite of sensitive instruments capable of seeing Ganymede in ways never before possible,” said Bolton. “By flying so close, we will bring the exploration of Ganymede into the 21st century, both complementing future missions with our unique sensors and helping prepare for the next generation of missions to the Jovian system—NASA’s Europa Clipper and the European Space Agency’s JUpiter ICy moons Explorer (JUICE) mission.”

Part of NASA’s New Frontiers program of medium-sized planetary science spacecraft, Juno’s extended mission means it’s now moving from a mission focused on studying the giant planet’s gravity and magnetic fields to a full system-explorer.

Wishing you clear skies and wide eyes.