Nigeria, also known as the giant of Africa because of its large population and economy, has traditionally had a thriving farming sector. Agriculture, the life-blood of the Nigerian economy, contributes to a third of the country’s GDP with more than 80% of Nigerians identifying as smallholder farmers who produce over 90% of the country’s domestic output on 33% of its land. But despite the sector’s significant contributions to economic stability and employment, the insurgence of armed banditry, terrorism, militancy, and kidnapping, have led to hikes in food prices and a increased reliance on imports.

The unprecedented rise in insecurity has displaced farming communities and hindered cultivation, leading Al Jazeera’s Ahmed Idris, to refer to kidnapping as “the fastest growing enterprise in Nigeria,” particularly in the largely ungoverned territories in the northwest of the country, with reports that hundreds of farmers were killed and kidnapped 2021 alone.

As a result, many farmers have abandoned their farmlands, fled their communities, and relocated to urban areas, or taken shelter in Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) camps. Many have become unemployed and can no longer care for their families, and in some cases they have resorted to criminality, leading to a vicious cycle of poverty and insecurity.

These disruptions have hurt agricultural supply and have led to inflated prices of agricultural produce. At a national level, since July 2020, staples such as beans and tomatoes have seen a 253% and 123% surge in prices, respectively. In July 2020, a measure of beans (called Mudu) sold for 73 cents (N305.48), but by July 2021, it was selling for $2.16 (N900). The prices of other commodities like bread, onions, and cassava flour, have also risen exponentially.

In Borno State, previously the largest wheat-producing state in the country, producing 30% of Nigeria’s wheat, the activities of insurgents popularly known as Boko Haram have stalled the cultivation of over 400 hectares of wheat in the area, as well as in other states in the northeast of the country.

As a result, Borno State now contributes minimally to the nation’s 420,000 tonnes of annual wheat production, leading to an increase in wheat imports to the country, from $2.4 million in the first quarter of 2020 to $6.2 million in the corresponding quarter of 2021.

In 2021, the armed conflict between Boko Haram insurgents and Nigeria’s security forces forced farmer Ismaila Mohammed out of Konduga LGA (Local Government Area) located about 25 km to the southeast of Maiduguri, to an IDP camp in Maiduguri, Borno State. Mohammed, age 47, remembers his thriving wheat farm with nostalgia, recalling thriving harvests that would yield over 250 bags of wheat annually with proceeds that would allow him to maintain a reasonable standard of living and give alms while catering for his family.

In Katsina State, located in the North-West of the country, kidnapping has taken center stage and disrupted agricultural activities. Many farmers have been kidnapped for ransom, and some have been killed on their farmlands.

In some instances, bandits have “struck deals” with farmers, “allowing” them to pay levies to continue farming on their lands. In cases where bandits have reneged, farmers have experienced attacks and where they have survived, they have been forced to flee their farms.

In 2021, in Kaduna State, in the North-West region of the country, eight farmers in Buruku and Udawa villages of Chikun LGA were attacked on their farmlands and eventually killed. This forced many farmers to abandon their farms and communities due to fear. One resident lamented, “We can no longer go to our farms because the bandits attack at will.”

Similarly, in the South-Western States of Osun, Oyo, and Ekiti, the rise in kidnapping has led to limited availability of labor for agricultural activities, as residents are no longer willing to engage in farming for fear of being abducted. As a result, there has been an unprecedented spike in the price of food items.

Amidst these overlapping challenges, residents have advocated for strategies that simultaneously address food security and national security as there has been a direct correlation between the criminal situation in the farmlands and rural communities and the food security of the country’s more than 200 million people.

Nigeria’s Federal Government, State governments and the military have been urged to tackle the menace of banditry and kidnappings by synergizing with local vigilantes who are knowledgeable of the hinterlands and terrains where bandits and terrorists operate.

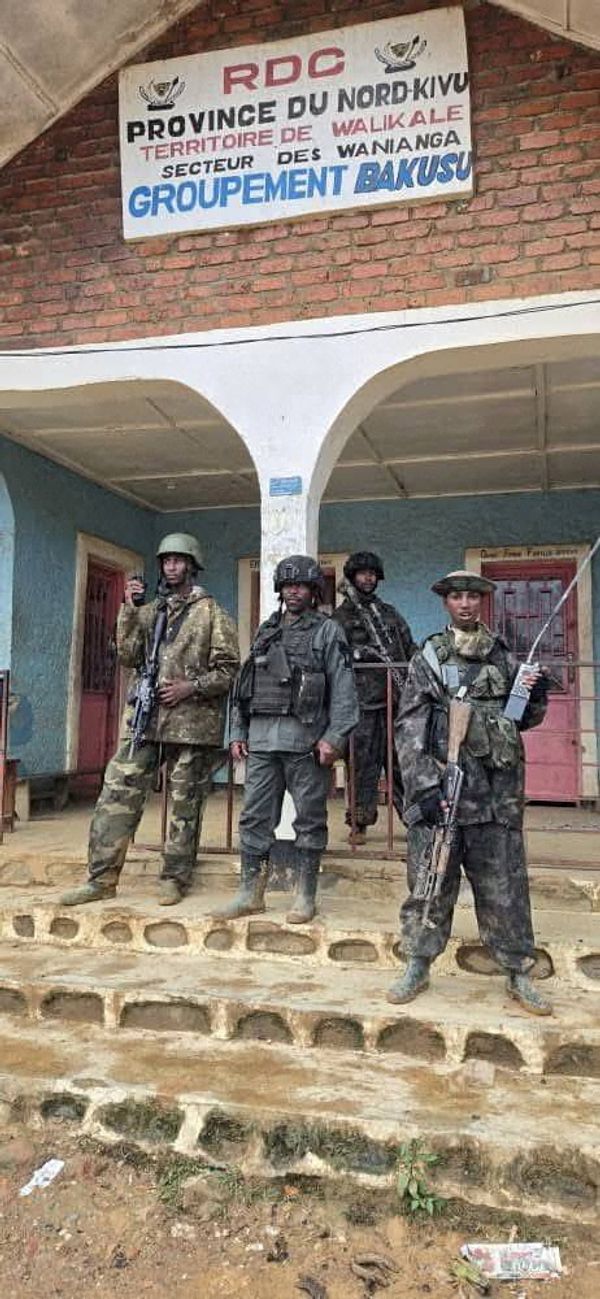

In this regard, the Civilian Joint Task Force (CJTF) consisting of local groups of volunteers has worked with Nigerian security forces in the fight against Boko Haram to provide security for internally displaced populations.

In January, the Nigerian government began to designate bandit gangs as 'terrorists' in a bid to curb violence, by imposing harsher penalties under The Terrorism Prevention Act.

Said President Muhammadu Buhari: "We labelled them terrorists... we are going to deal with them as such."

That month, Nigeria’s armed forces reported killing 537 “armed bandits and other criminal elements” in the region and have arrested 374 since May 2021, while rescuing 452 kidnapped civilians.

By addressing Nigeria’s rising security crisis, government will be able to alleviate food supply deficits and stabilize escalating uncertainty around food prices so that it can meet its objectives of increasing the country’s food security index from 40.1 in 2020 to 60.1 by 2025 while reducing the prevalence of severe food insecurity from 19.6 per cent in 2020 to 10 per cent by 2025.