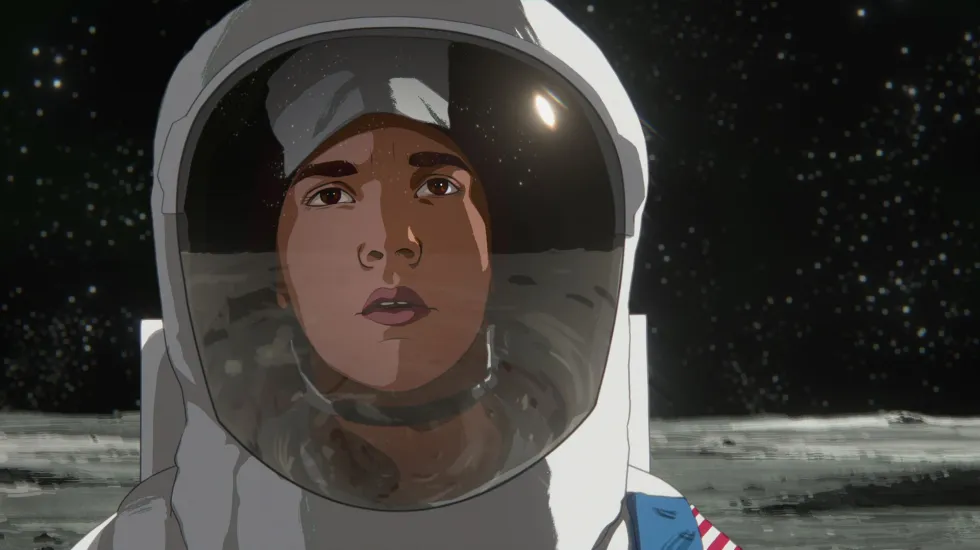

The geniuses at NASA accidentally build the lunar module a little too small for an adult in “Apollo 10½: A Space Age Childhood.” In Richard Linklater’s first foray into animation since “A Scanner Darkly,” a few fast-talking NASA men (Glen Powell and Zachary Levi) recruit an average local elementary school student, Stan, to test it out for them on a top secret mission to the Moon. It’s the kind of thing kids have been dreaming about for over 50 years.

Memory is a funny thing, of course, and no one fantasizes as freely as a kid. For this imaginative spirit living in the Houston area in the late 1960s near NASA at its heyday was like “being where science fiction was coming to life. The optimistic, technological future was now and we were at the absolute center of everything new and better,” he says.

Netflix presents a film directed by Richard Linklater. Rated PG-13 (some suggestive material, injury images and smoking). Running time: 98 minutes. Now streaming on Netflix.

It should be said that our narrator Stan (Milo Coy voices him as a kid, Jack Black as an adult) is a bit of a fabulist. Not that it matters, “Apollo 10½” is only sort of about Stan’s fantastical trip to the Moon before Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins took off in Apollo 11. It is a breezy nostalgia-fest, in rotoscope, about a very specific childhood in a very specific place with an adult narrator telling us the story of his childhood. His siblings teased him for not being in many family photos because, as he says, at that point his family had given up on documenting every move of their children.

And it is not dissimilar to retrospective coming-of-age larks like “Stand by Me,” “Now and Then” and “The Wonder Years,” with its earnest, wry observations. Stan takes us through daily life as a 10-year-old in 1969 as the youngest of six children in a neighborhood where it seemed like everyone worked for NASA in some capacity, though he can’t help but wish that his dad had a position that took him to space, not an office.

Linklater is almost too good at making you wistful for times you were never part of. And even so, there is universality in Stan’s life in the sandwiches they would make on Sunday and unfreeze throughout the week for school lunches, the myriad ways his mother would use a ham for a weeks’ worth of dinners, or memories about seeing “The Sound of Music” multiple times a week for at least a few years straight.

Stan explains he was part of the last of the “duck-and-cover” generation, though hardly the last to fear that there would be no future at all.

There’s a paradox to living in a time that worships the future while also predicting the end. As if kids don’t have enough anxiety already.

And for Stan this is manifested in a strange reality where the space race seemed to permeate the most mundane aspects of daily life, from the wire rockets on their playgrounds and the desperation to give everything — even advertisements in the newspaper — a connection to the astronauts.

There may be a little bit of projection going on in regards to Stan’s immediate appreciation of “2001: A Space Odyssey.” He’s either the coolest 10-year-old film scholar out there or this is also a riff on our fallible memories. Who’s to say Stan (and Linklater) didn’t really get the famous white room? There’s also the unshakable feeling that we’ve seen this all before. We kind of have: 1969 is not exactly an undocumented time, especially for a middle class white family and this doesn’t push many boundaries.

And yet as with most Linklater joints, it’s so sincere and so sweetly true that you can’t really fault it for not reinventing the wheel. Just like a story that your parents have told or maybe you’ve told a million times before, it’s comforting. So put that ham casserole on the stove, pull up a chair and enjoy hearing one more time about how someone who grew up with a black-and-white television set never knew Oz was in color.