Our cities sometimes appear inevitable. Once something is built, it’s difficult to remember what the landscape was like before—before a highway cut through a neighborhood, before an office tower hovered over a downtown, before a housing development carved up a wetland.

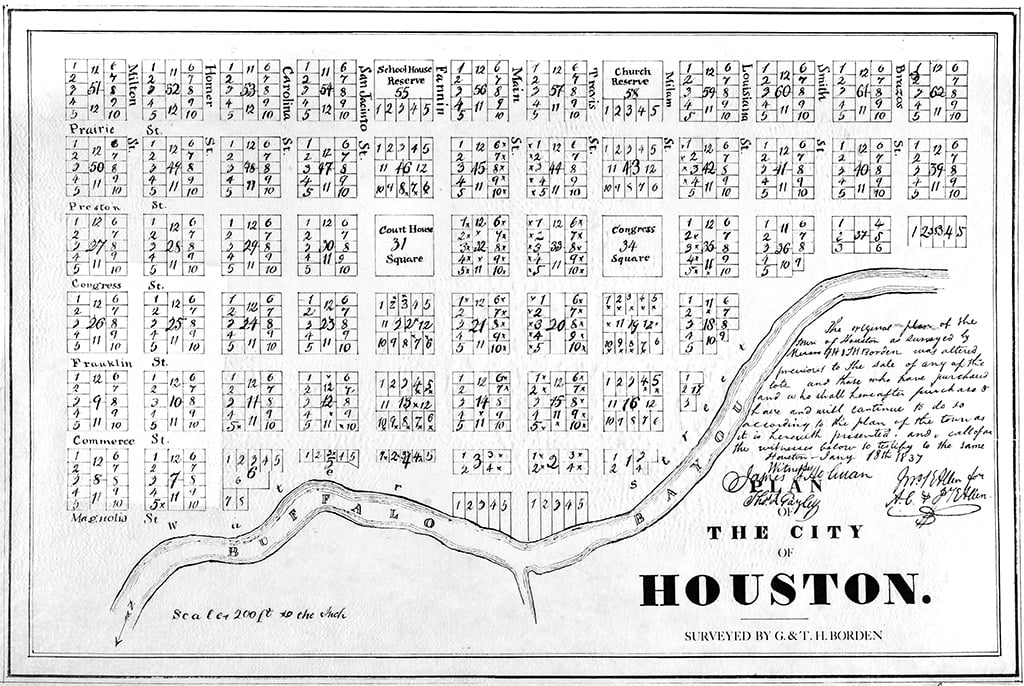

But in 1836, when Houston’s founders, Augustus Chapman Allen and John Kirby Allen, envisioned “a great interior commercial emporium of Texas,” the city was just an idea, a vision projected onto a swampy prairie at the confluence Buffalo and White Oak Bayous, once home to the Karankawa and Atakapa tribes. So how did Houston become Houston?

Two new books about the Bayou City—one about its people, one about its places—provide compelling answers to that question. Both Prophetic City: Houston on the Cusp of A Changing America and Improbable Metropolis: Houston’s Architectural and Urban History offer layered, nuanced histories of this ever-evolving city. If Houston’s dizzying growth over the past half century offers a glimpse at the future of the United States—multicultural, sprawling, unequally prosperous—then, these books suggest, by understanding how we got here, we can better understand where we’re going.

In the spring of 1982, a sociology professor at Rice University named Stephen Klineberg was teaching a class on research methods, instructing his students on how to design a systematic survey of their classmates. At the time, Houston was “a different place from the rest of America,” he writes. “It was an arrogant, spread out, automobile-dependent boomtown while most of the country was in recession.” When a professional research firm reached out and asked if he wanted to partner on a city-wide public opinion poll, he jumped at the opportunity to give his students the opportunity to study the whole of Houston, to get a sense of “the kind of city its inhabitants were hoping to build with all the oil-based affluence.”

In May of that year, two months after the class completed their survey project, the oil boom became a bust. The price of a barrel of oil fell from $35 to $28 overnight. By the end of the following year, more than 100,000 people had lost their jobs. It was clear, Klineberg writes in Prophetic City, the survey should continue.

Thirty-nine years later, 45,000 Houstonians have talked to his team of researchers—now housed at the Kinder Institute for Urban Research, which Klineberg directs—making the Houston Area Survey the longest-running study of any city in the United States. As Houston grew at a dizzying pace, as the city attracted immigrants and refugees from across the world and the economy cycled through booms and busts, researchers were there, calling people up for a 30-minute chat on the telephone.

Prophetic City tracks not just the changes that led Houston to become America’s fourth most-populous city, but also how residents felt about those changes as they were happening. Over time, Klineberg reports, Houstonians have become more socially progessive and accepting of LGBTQ people, immigrants, and refugees. A Houstonian today is more likely to support public education and environmental activism than they were in 1982. Residents are more likely to oppose the death penalty and support more stringent government regulation.

Klineberg notes that these increasingly progressive attitudes have been slow to make their way into public policy, but he offers frustratingly little analysis as to why. “The loudest voices… in the Texas Legislature are generally anti-gay, anti-immigrant, and pro-death penalty, even though most Americans (and most Houstonians), when interviewed in the privacy of their homes, take decidedly more progressive positions on these and other issues,” he writes. Perhaps it is because many people self-report themselves to be more tolerant than they actually are. Perhaps it is because, over the past four decades, politicians have made it increasingly hard for Texans to vote and express those progressive positions. Ever the sociologist, Klineberg doesn’t speculate.

Despite the decisive shifts in public opinion captured year after year, Klineberg’s body of research demonstrates, compellingly, how uneven change can be. In 2004 and then again in 2016 and 2017, researchers asked Houstonians about how they felt about living in racially diverse neighborhoods. “Despite clear evidence of their overall positive and improving assessments of ethnic relationships in Houston,” Klineberg writes, “Anglos were just as resistant in 2017 as they had been in 2004 about moving into an integrated neighborhood.” And they were very resistant: In 2017, 48 percent of white people surveyed wouldn’t buy a house in a neighborhood that was 60 percent Black. Fifty-eight percent wouldn’t buy a house in a neighborhood that was majority Hispanic.

Again, Klineberg simply reports the facts, leaving it to others to offer judgements. “Houston,” says John Guess, the CEO of the Houston Museum of African American Culture, “is a much more deeply racist town than the surveys reveal.”

If a city can be understood as a collection of human stories, then perhaps those stories are written upon our built environment—collected in the buildings that contain our lives, the places we work and learn and pray. Through a mix of archival images, maps, and text, Improbable Metropolis traces the development of Houston over two centuries as the town transformed from a flood-prone swamp to a sprawling, cosmopolitan city.

Famous for its lack of zoning and “spirit of speculation,” Houston is decidedly less famous for its architecture. The former editor of Cite: The Architecture and Design Review of Houston, author Barrie Scardino Bradley attempts to correct the record, defending the city’s no zoning policies as fostering creativity and innovation in the built environment. Things are possible in Houston that simply aren’t possible elsewhere: “Houston’s architecture, an indicator of its culture and prosperity, has been inconsistent, often mundane and predictable, sometimes bizarre, and occasionally extraordinary,” she writes.

How did Houston’s urban personality emerge? There are the structures of the white and wealthy—hotels and banks and museums. There are the famous parks, the emergence of a world-class medical center. But in Improbable Metropolis, Bradley also captures the vernacular architecture that defines much of the city. For example, in the Third and Fourth Wards, “identical, small, wood gabled-roof houses were three rooms deep, one room behind another, usually with a small stoop in front and back.” These row houses, with their shared outdoor spaces, served as community centers for Black families in neighborhoods settled by freed slaves after the Civil War. Over the decades, many homes fell into disrepair, neglected by absentee landlords and the city itself. In 1993, a group of artists bought 22 of these historic homes, relying on volunteer help to rebuild the structures into studios and galleries.

But restoration has never been one of Houston’s strengths. Instead, the city tumbles forward, rebuilding what it no longer requires. In 1883, architect George E. Dicky unveiled the B.A. Shepherd Building to house the First National Bank of Houston, becoming the city’s “best example of a commercial house with High Victorian Gothic features,” Bradley writes. But change soon came for it, too: “The Shepherd Building ended ignominiously as the Pink Pussycat Lounge before it was demolished for a Harris County parking garage in 1989.”

Indeed, the demolition of the city’s historic buildings tells as vivid a story as does their construction. In 1913, when Black people were legally barred from visiting the new Houston Lyceum and Carnegie Library, prominent Black businessmen purchased property in the Fourth Ward and contracted William Sidney Pittman, the son-in-law of Booker T. Washington and one of the foremost architects in the South, to build the Carnegie Colored Library. “This building served the African American community until it was demolished for freeway construction in 1962,” Bradley reports.

As the Texas Department of Transportation considers expanding yet another freeway in Houston, in the process demolishing historic structures in its pathway—including dozens of homes in Independence Heights, the first city in Texas incorporated by Black people—and relocating a historic church, it’s an apt moment to consider the city that today’s residents never got to see.

Above all else, both Klineberg and Bradley capture Houston as a city of transformation, something always in the process of becoming something else. In urban Texas, so many of us are from someplace else, amnesiacs in the places we live. As we consider how to build better, more equitable cities, it’s worth examining what we’ve inherited and who we’ve become. In a place as dynamic as Houston, where each generation creates a new city from the foundation of the old, the only thing that is truly inevitable is change.

Read more from the Observer:

-

From Boom to Bloodbath: The Permian Basin’s shale revolution is over and renewable energy is surging. What does that mean for Texas’ future?

-

In Harris County, A Group is Working to Expand Voting Access in Jails: The lack of access for eligible voters in pretrial detention is part of a larger constellation of disenfranchisement for people whose lives intersect with the criminal legal system.

-

Houston’s Hot-Stepping Zydeco Dance Fuses Creole and Black Cowboy Cultures: For many of these dancers, musical gatherings are just one aspect of a lifestyle rooted in their Creole heritage: trail riding by day, zydeco dancing by night.