Dudley Clifford ‘Tal’ Stokes stood atop of the bobsleigh track determined to make this race one to remember. Little did he know it would go down in history, that movies would be made about it and that his legacy would be immortalised.

Stokes came from humble beginnings, born on Turks Island to two Jamaican missionaries that sailed around the islands opening churches and preaching.

When he turned five, they moved back to the north coast of Jamaica to continue to spread the gospel. Stokes spent his childhood running through the hills, fishing in the ocean and playing football.

At 15, he was dropped from his school football team. He came home crying to his mother, who then marched up to the school with a pen and paper. She came back with a list of his weaknesses and said, “this is why you’re not in the team.” This was a life lesson for Stokes – break down your flaws and work on them.

Once he finished school, the family moved to Montego Bay where Stokes joined the army. After a few years, he moved to Canada, learnt to fly helicopters and became a pilot for the Jamaican military.

“It was while doing that, I met the Americans that had the idea for the Jamaican bobsled team. George Fitch and William Maloney,” Stokes says. “George was friendly with the colonel in charge of sports in the army. He asked him for some athletes they could teach to drive a sled.”

By this time, Stokes had developed into an aerial powerhouse of a centre-back for the army’s football team – after idolising Derby County defender Roy McFarland. Due to his football abilities, he was shortlisted for the bobsled team.

“I had to think about [bobsleighing] because my first reaction was ‘these guys are insane’,” he says. “As I was a helicopter pilot, I enjoyed controlling things with my hands. When I found out that it actually had to be driven, I was intrigued.”

Thirty athletes turned up, they were shown a video informing them about the sport (most notably the crashes) and by the time the video was over, two-thirds of the room had left. George and William judged the 10 that remained. Stokes was selected to be the driver of the four-man and a two-man sled.

“The only training you can do in Jamaica is the training you can do for the start. Which is a very important part of the race, it can often decide a race. But you can’t practise the drive,” Stokes says.

“One of the things I discovered early on was mental rehearsal. In my career, I have fewer actual descents around a bobsleigh track than most athletes have in a year. I made up for that through mental relaxation, visualisation and knowing the track intimately.”

This is a skill he takes out of the track and into his everyday life. Now he teaches it to others as a performance coach, calling it the “most important skill” he has ever learnt.

By the time they got to Canada for the Olympic Games, they were world-famous. They’d been in Time magazine, People magazine and plastered all over the television. This was a concept that Stokes struggled to come to terms with as they hadn’t done a single thing… yet.

Ten days before the first race of the Olympics, Stokes’ brother, Chris, stepped in as a last-minute replacement. He’d been in a bobsleigh three times before competing.

On the first day of racing, things weren’t great. The American commentator branded it “untidy” after they struggled to load onto the sleigh in their first two runs. To make matters worse, Stokes slipped on the ice and broke his collarbone but was patched up by another nation.

The boys reviewed the tape and Stokes gave instructions to the others. He was determined to make their next race one to remember.

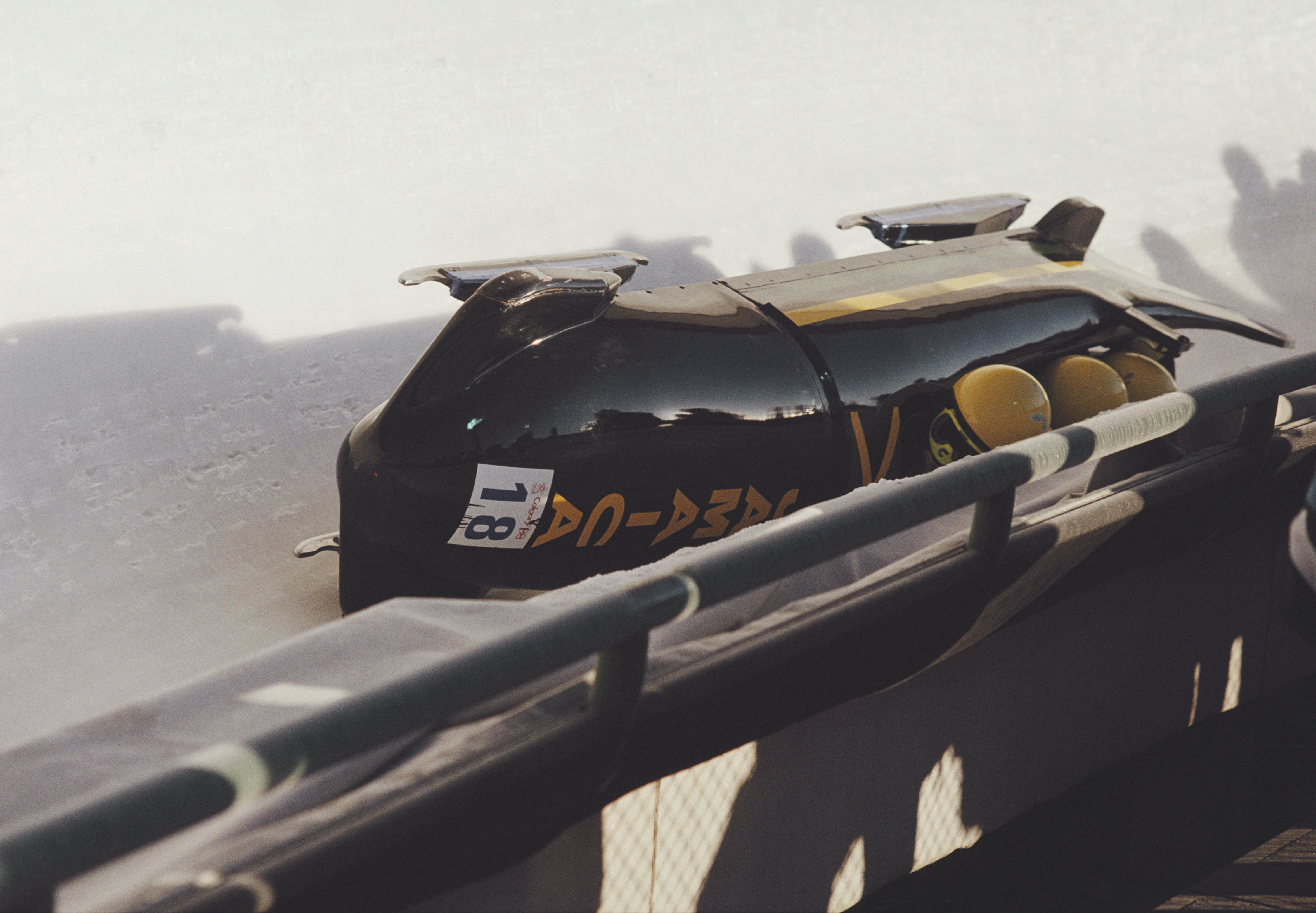

This time the load was good. Tightly packed, but it was much quicker. The helmet of Devon Harris was digging into the back of Stokes, which was both distracting and painful. Six turns in and the ride was going fine.

On the seventh turn, Stokes started to sense he was losing control. He’d come out too high and bumped into the wall.

The eighth turn was the kreisel of the track, one of the longest and hardest turns. Stokes was already behind, the team started to rise up the wall and came out of the turn by crashing into the wall.

On the broadcast, you can see Stokes’ head smash into the wall, the bobsleigh capsize and continue to slide down the course with the team inside of it.

“When I first hit my head, it was a life-flashing-before-your-eyes moment,” Stokes says. “Growing up, parents, wife, my brother – who was also on the back of the sled. It couldn’t have been long but I was thinking of all the things that mattered.”

The team slid with their heads scraping on the track for 28 seconds (2,000ft) while the crowd watched with bated breath. For the first 10 seconds, Stokes struggled and attempted to protect himself. He couldn’t move. Soon he accepted his fate and relaxed.

In that relaxation, Stokes dissected their problems and how to fix them. He thought: “We need money. We need to travel. We need equipment. We need coaching. We need training.”

By the time they’d stopped moving, he’d seen the next Olympic Games. Thankfully, everyone was okay. In the ambulance, he relayed the plan to his brother and the rest of the team.

He got home and people were going crazy. Again, Stokes couldn’t understand it. He was battered, bruised and carrying a broken collarbone after the games, so stayed at home for two weeks.

The Olympics was the first time he’d been exposed to computers and they amazed him. For this reason, he taught himself how to use a typewriter. What should he write? The plan for the next Olympics.

Two Olympic games later, Stokes and his crew finished in 14th place, as the seventh-highest nation, ahead of the Americans.

Stokes still continues to impact Jamaican winter sports and is working as a personal performance coach for Benjamin Alexander, who will compete as the first Jamaican downhill skier at Beijing 2022.

The 1988 Jamaican bobsleigh team has forced winter sports to be taken seriously on the island. They won’t be any more comedy movies about Jamaica in the Winter Olympics. Instead, other countries will look at them as serious opponents.

“What I consider my legacy to be,” he says, “is going from comedians to competitors.”