A solitary orange chair in the middle of a courtyard. Doors set into colorful walls, dappled with sunlight and shadow. A mural of a fortune-teller, marred by a crack. More than 100 five-by-seven-inch photographs stretch in rows across a white wall at the Centro de Artes in San Antonio. They look like images a traveler would collect during vacation as she explores unfamiliar territory, training her camera on eye-catching details. But the title tells a different story: “Retomando Nostalgias” is the work of three artists from three countries, revisiting memories of home.

“It’s like one collective nostalgic memory,” said Venezuelan artist Hayfer Brea Rodriguez, through an interpreter, of his and his colleagues’ photography.

The photos are part of Admitted: USA, an exhibition of work created by artists in the inaugural round of the New York Foundation for the Arts (NYFA) Immigrant Artist Mentoring Program in San Antonio. The initiative pairs artists who were born outside the United States, or whose parents were born outside the United States, with mentor artists who orient them to the local creative scene and help them fine-tune their professional skills. NYFA started the project in 2007 and, since 2017, has expanded it to other cities including Detroit, Newark, and Oakland.

For the San Antonio program, NYFA selected an initial group of San Antonio immigrant artists in 2018 with input from mentors nominated by local arts nonprofits. The mentees included immigrant artists from eight countries, as well as U.S.-born artists whose parents grew up in another country. The work of both mentors and mentees is on view at the Centro de Artes in Market Square through September 29; meanwhile, a second round of artists and mentors completed the program this year.

“We wanted to put a face to the word ‘immigrant,’” said Kim Bishop, one of the San Antonio mentor artists and the lead organizer of the exhibition. “That’s what this country is made of: We’re all immigrants or have immigrant ancestry.”

The fact that the artists are immigrants doesn’t mean their works all focus on immigration. Some do: The 15 photographs in Venezuelan artist Merle Mory’s “Immigrant Children Crossing the Border” show the faces of Central American children Mory met while working with asylum-seeking families through Catholic Charities. A few smile at the camera; several blink back tears. Mentor Anne Wallace’s untitled installation employs objects discarded by migrants who made the dangerous journey through the Sonoran Desert. Shelves of empty water jugs sit beneath squares of tattered clothing, strung overhead like prayer flags.

In other works, the connection to immigrant identity is more subtle. Mentor artist Guillermina Zabala grew up in Argentina and moved to Los Angeles to attend film school and work in the film industry. Fifteen years ago, she came to San Antonio, where, she said, the supportive art community helped her start making her own work again, this time in photography, video, and printmaking. Her “Flores Negras” series was inspired by the global women’s movement against sexual and domestic violence and the experiences of friends who’ve endured abuse. The artworks combine photographs of women’s bodies with relief prints of black flowers, a symbol of beauty that endures in the face of trauma.

One of Zabala’s two mentees is Jorge Villarreal, whose luminous photographs of faded and peeling paint on exterior walls glow like polished gemstones. A decade ago, Villarreal, who grew up in the Rio Grande Valley, started traveling to Cuba and documenting the changing architecture in Havana. Over time, he began to pay closer attention to details of the buildings’ walls, particularly the colors and textures that emerge as paint deteriorates in the salt air. Now, Villarreal said, he searches for walls with this decaying beauty everywhere he goes: Mexico, India, his hometown of McAllen.

“The way I work best is if I don’t know where I am,” Villarreal said. “That’s where I’m more sensitive to finding details in my surroundings.” That feeling is reflective of the immigrant experience, he added, in which the immigrant is a little lost, a little on edge, and thus keenly aware of his environment.

The sense of being an outsider, both in one’s country of origin and in one’s adopted home, is a hallmark of the immigrant experience. “You’re not here, you’re not there,” Zabala said. “You have an outsider’s point of view.” Villarreal echoed that: “When I visit my cousins in Mexico, they all consider me the gringo, and all my friends here consider me the Mexican.”

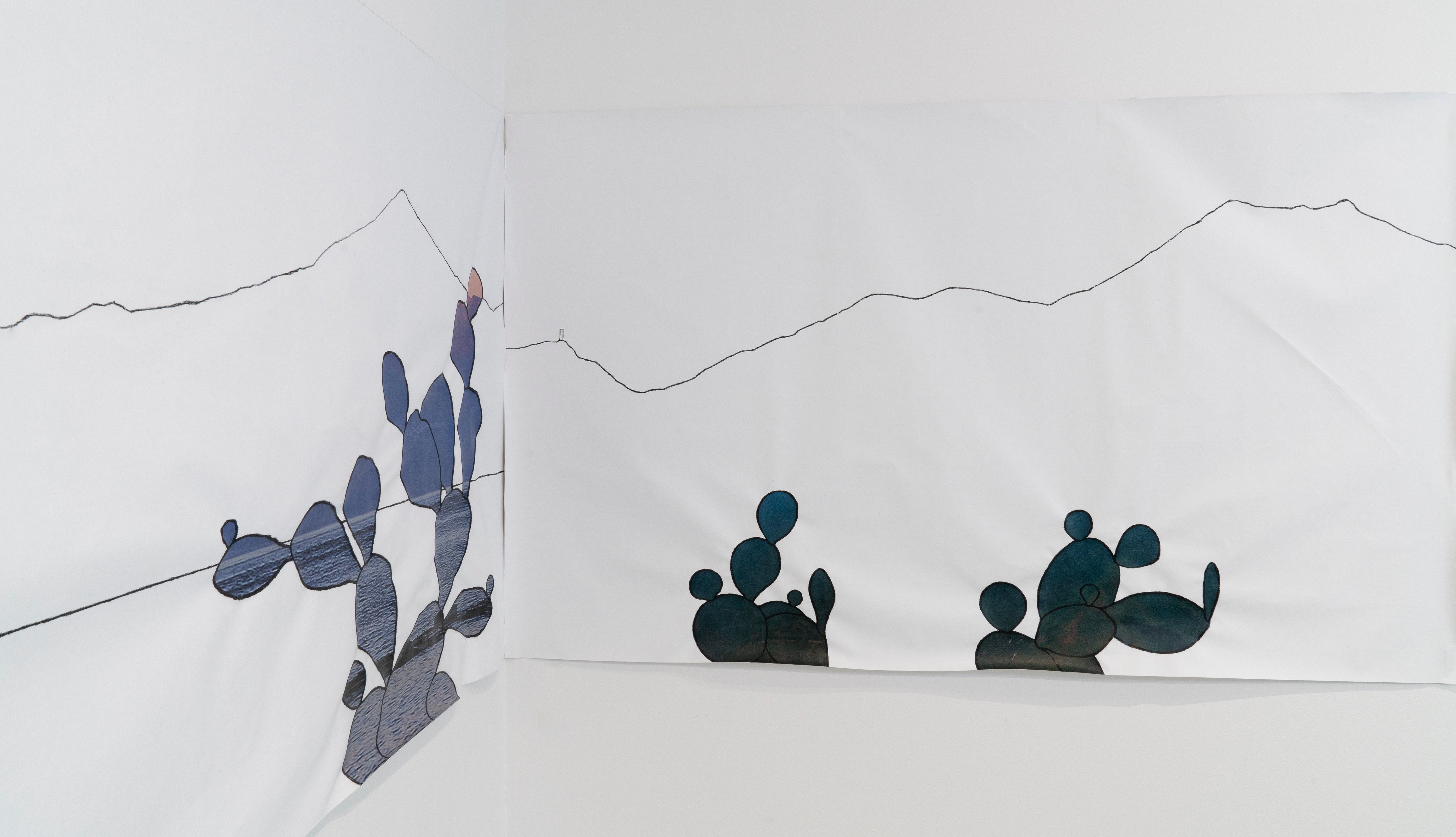

At the same time, that outsider viewpoint sharpens an artist’s perception. Zabala’s second mentee, Hayfer Brea Rodriguez, created a mixed-media piece that features four images of a cactus against a minimal landscape. Each represents a significant place in Brea’s life: his hometown of Caracas; the Caribbean sea that laps at Caracas’ shores; the Canary Islands, where his family came from; and San Antonio. Every landscape, Brea said, has the same cactus, the motif that ties the four works together.

“Being an immigrant artist helps you become a universal artist,” he said, with interpretation assistance from Villarreal.

Brea was an established artist in Venezuela and had a solo show at the Museum of Contemporary Art of Caracas shortly before he came to the United States three years ago, fleeing political and economic instability. Coming to San Antonio meant starting over, in terms of building a network and learning how the arts ecosystem worked. The mentorship program, he said, helped him connect with potential collaborators.

Zabala and the other mentors introduced their mentees to the terrain of San Antonio’s art scene: exhibit spaces, public art opportunities, key nonprofits, the First Friday and Second Saturday Artwalks in Southtown. The mentors also went over professional skills Villarreal said he didn’t learn in art school: how to write an artist statement and grant proposals, apply for public art commissions, and manage social media as a marketing tool.

Zabala, Villarreal, and Brea were one of several mentor-mentee teams who collaborated on new work for the exhibition. Because all three use photography as a medium, they decided to create “Retomando Nostalgias.” Villarreal contributed photos of the border wall between McAllen and Reynosa and of the midcentury Echo Hotel in Edinburg. His image of a South Padre Island sign reading “Road Ends Ahead”—the sign, not to mention the road, is already consumed by sand dunes—reminds him of skipping high school to hang out at the beach. Zabala’s images include several of her own high school, as well as public memorials to four students from that school who were abducted and killed in 1976, during the Videla dictatorship. Brea contributed views of the mountains in Caracas, the building where his grandparents live, and photos of eye-catching chairs he found in the street.

The installation’s title roughly translates as “Revisiting nostalgic memories,” although Zabala describes “nostalgia” as a memory that’s particularly heavy with emotion. “It’s a recollection that’s deep in your heart, and that’s also very common in immigrants,” she says. “They will tell you they feel nostalgia from home—that feeling of emptiness, that you’re missing that part you left behind … I think that’s what we want to say: All these places are part of us, and we left them behind.”

READ MORE:

- The Clothes That Make the Man: Jose Villalobos’ art redresses the macho traditions of norteño culture.

- At Home in the World: Houston artist Prince Varughese Thomas blurs boundaries of politics, medium and identity.

- Uncaged Art: Finding life and light in art from detention.

.jpg?w=600)