Ariel Hollis doesn’t know what she would do if she lost her daughter’s day care.

If the Near North Side center closed or she was no longer able to cover tuition, she would have to work less to care for her 4-year-old. That loss of income would make it hard to pay her bills.

“That’s almost as worse as taking away my medical benefits. That’s almost as worse as taking away my life insurance,” Hollis said. “Where would I be without my day care, the people that help me to raise my child?”

That nightmare could become a reality for many Chicago parents as pandemic-era federal funding that helped stabilize the child care industry expires Sept. 30, triggering a crisis for providers and the families who depend on them.

For Illinois, that could mean nearly 130,000 kids without child care, about 2,800 shuttered centers and over 11,300 child care providers without jobs, according to a study from the Century Foundation, a think tank headquartered in New York.

“We have long had child care challenges in this country, well before the pandemic,” said Julie Kashen, director for women’s economic justice at the Century Foundation.

“You’ve got parents paying too high a price, you’ve got early educators being paid poverty-level wages. So you start with this broken, unaffordable market and a scarcity of child care programs at the same time. Then the pandemic came along,” said Kashen.

The industry faced collapse as centers had to close due to COVID-19. In response, the federal government provided states $24 billion to bolster the child care sector through the American Rescue Plan in 2021.

Those funds stabilized and ultimately saved child care businesses in Illinois, advocates, policy experts, child care providers and parents told the Chicago Sun-Times. Without them, the industry once again risks collapse.

“It worked. It did what it was supposed to do. Child care programs were able to keep their doors open to continue to serve children. They were able to raise wages for the early educators, at least temporarily,” Kashen said.

“It made a huge difference. And it gave us a view of what it could look like if we actually built the system that families need,” she said.

‘Who’s invested in us?’

Illinois has provided nearly a billion dollars in grants from the federal government to over 12,000 child care centers and home-based day cares during the last two years, according to the Illinois Department of Human Services.

The money was largely used for staffing. Without additional money, many centers have to decide whether to increase their prices, reduce their staff’s wages or close their doors, Kashen said.

“The dollars that were allocated to support child care through the pandemic were so needed,” said Tamera Fair, CEO of Premier Child Care, which has centers in Austin, Pill Hill, Hegewisch and the Near North Side. The four centers received over $800,000 in federal support over the last two years, according to state data.

“We were very encouraged by the dollars because robust child care is a necessity for a robust economy,” Fair said. “That also showed how needed a stable child care system is in the U.S.”

For Fair’s centers, that money meant they were able to retain staff, give them hard-earned raises and start matching their 401(k) contributions. Losing that financial stability will make it difficult for her to retain and attract providers.

“When teachers spend four years in school, only to make a little above minimum wage, receive few or no benefits, work 12-hour days, it makes it hard to keep teachers around,” Fair said.

The average income for child care workers is $27,860 to $31,580 per year in Illinois, according to the U.S. Department of Labor.

“They’re setting us up for failure,” Fair said. “They expect so much from us. They built us up but now expect us to keep up on our own when we’re dealing with factors out of our control.”

Meanwhile, the cost of child care remains high. Cook County families spend about 20% of their income on child care each year, according to Labor Department statistics. The average annual cost is estimated at $17,400.

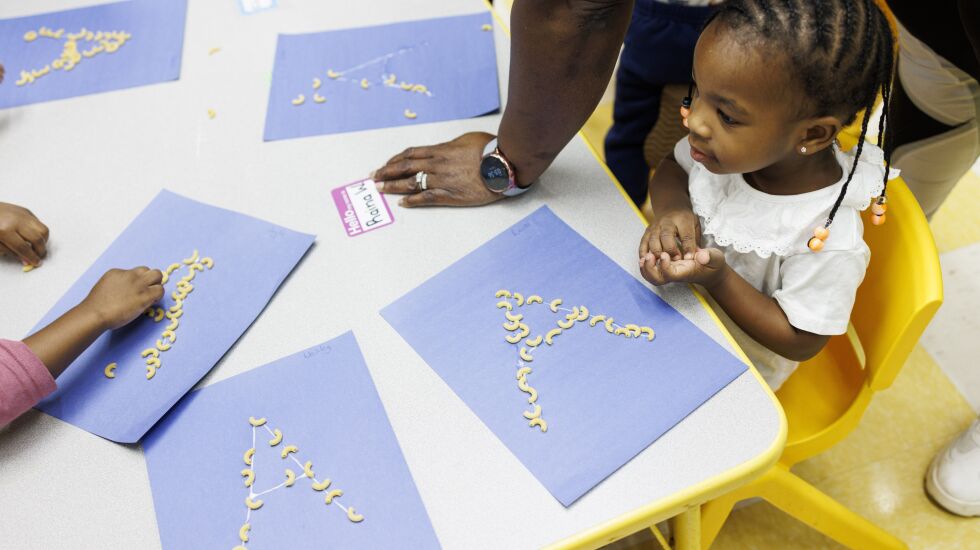

Hollis works as a provider at the Near the Pier STEAM Development Center, which is also where her daughter attends. She said she hopes more funds are made available to pay workers better wages, without making it more expensive for parents.

“I get to see how much the workers pour into our children, even with being underpaid and overworked. We’re not working here for the money because we don’t get paid a whole bunch,” Hollis said.

“We don’t complain because we care about the kids. We want them to grow. We want to invest in them because they are our future. But who’s invested in us?” she asked.

State support

Illinois has started investing into early child education to minimize the upcoming dearth in federal funds, said Angela Farwig, vice president of public policy, advocacy and research for Illinois Action for Children.

Smart Start Illinois is a multiyear plan from Gov. J.B. Pritzker to bolster the state’s child care industry. This year, the state allocated $250 million to eliminate preschool deserts, stabilize the child care workforce and expand early intervention programs.

A key part of that funding also goes toward transition grants to help child care centers deal with the loss of federal funding. But that money alone won’t fill the gaps.

“We’re just going to continue to see a system that was already incredibly squeezed and was given a lifeline, only to start to be squeezed again. There needs to be more of an investment on the federal side. States cannot do this alone,” Farwig said.

One way to address the crisis, Farwig said, is to expand eligibility for the state’s program that helps low-income families afford child care.

Currently, the Child Care Assistance Program helps pay for part of a parent’s child care bill as long as their monthly income doesn’t exceed 225% of the federal poverty level.

Farwig said Illinois Action for Children has been lobbying the state to increase that percentage to 300% so more families can be eligible for the program.

Making that change would help parents like Hollis, who depends on the state assistance program to cover her daughter’s day care tuition. She couldn’t afford the center’s $2,315-a-month price tag otherwise.

“It’s hard enough as is to qualify, and sometimes covering the co-payment is tough,” Hollis said. “Take the load off the parents by making the bill more affordable so they can have one less worry.”