In 2016, six years before his death, Prog was granted a rare interview with Vangelis Papathanassiou in his Paris studio, where he explained his philosophy of music and his relationship with it.

“Every time a sound comes out of my hands, it has been and is always instinctive. There is no thinking and I don’t have any preconceived ideas or any preconceived plans or construction. I follow this flow until the music doesn’t need me any more.”

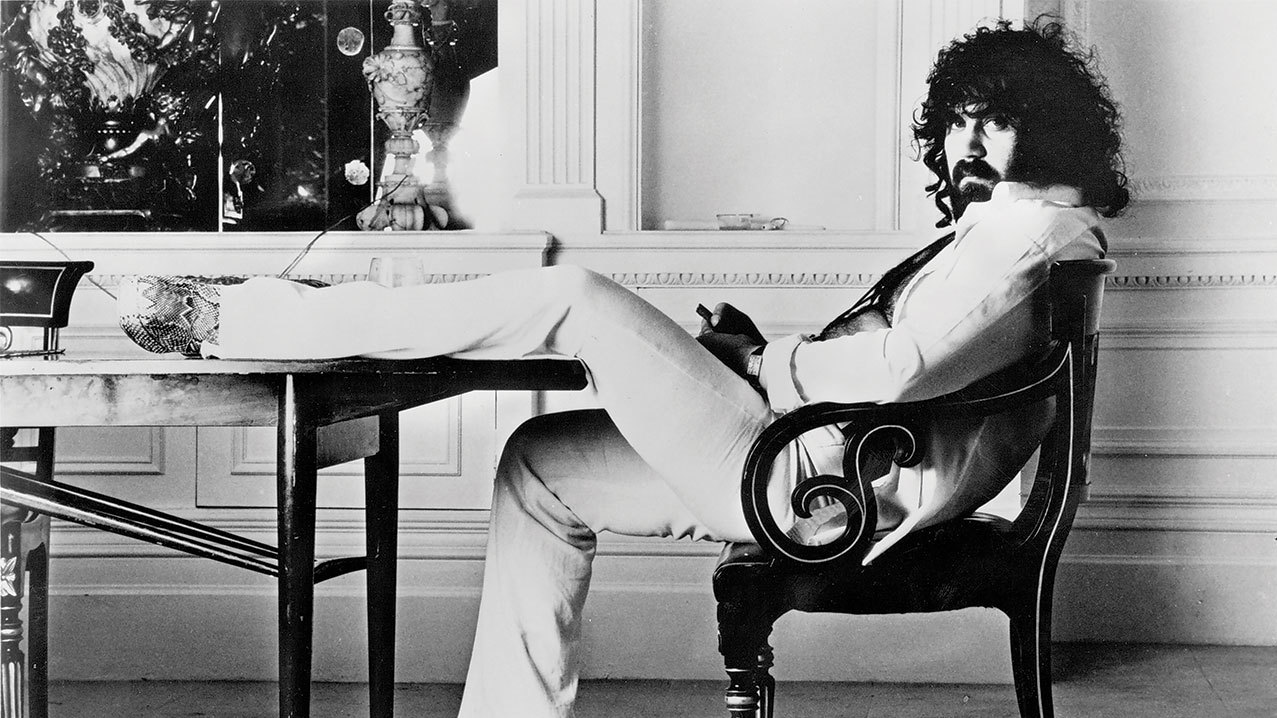

It’s no secret that Vangelis Papathanassiou is a notoriously private man who has rarely given interviews throughout his career. The value of such activity rarely bothers him, as his focus shifts to the next creative project by the time any new album is released. However, with an impressive 13-disc box set, Delectus, on the way – covering all of his work for the Vertigo and Polydor labels, including the Jon & Vangelis albums – and with the recent release of Rosetta, his first non-soundtrack album since 2001’s Mythodea, Prog is granted a rare audience with the great but reclusive man.

Our original meeting gets postponed due to him being engrossed in a new creative project. This does little to ease the trepidation that maybe we’ll go home empty-handed, but thankfully everything is rearranged for the following evening at his residence and studio in central Paris.

When we do meet, we’re confronted by a man of sharp intellect, possessed with warmth and a fine sense of humour. Over an initial dinner, he reminisces about the 14 years he spent in London, his love of the variety of British accents, British comedy and Ealing Studios films.

“It was a great time in my life,” he laughs. “Culturally it was quite different when I first arrived in England in the mid-70s, but I did learn to adapt. Coming from a different culture, where cafes and restaurants were open late, I was surprised when I realised most things closed by 10.30 in the evening, as they did in the 1970s in Britain. At my home here in Paris I have a street sign for Hampden Gurney Street, where my old studio was located.”

Following dinner, we’re granted an even rarer invitation into his studio to hear brand new music he’s working on. Needless to say, it takes our breath away. For Vangelis, however, creation of such music is a daily occurrence. As he observes after listening to the pieces: “It’s important to understand that for me, making music is a process that is as natural and instinctive as taking a breath.

“If a musical piece I create lasts for six minutes and 30 seconds, it usually means it has taken me that time to create that piece,” he says of his compositional philosophy. “This is due to the system of recording and the technique I’ve developed through the years. When the moment is right and I start playing, I can have access to any sound I need, or rather what the music needs, immediately, which makes my work more complete.

”With this method I don’t have to go through the process of mixing because the mix happens during my performance. It’s a very liberating way to work. I sometimes listen back to pieces I may have recorded some months earlier and wonder where they came from, but it’s important just to follow the moment, when those moments come, and to not be afraid of making mistakes.”

We were stranded in France and had no money. I couldn’t even call home to Greece to ask for assistance, so I decided to call Mercury Records in France, who offered us a deal

His most recent work is the aforementioned Rosetta. September 30, 2016 was a significant day in the history of space exploration. The European Space Agency mission to the comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko came to a dramatic conclusion when the Rosetta space probe was crashed into the comet, upon which in November 2014 it had successfully landed its lander module, Philae. It was a triumph of international co-operation and scientific achievement.

The album project began with a video call between Vangelis and European Space Agency astronaut André Kuipers in 2014, while Kuipers was on board the International Space Station. Inspired, Vangelis offered to compose music to celebrate the Rosetta mission.

“My first encounter with space projects was when I met Carl Sagan,” he says. “He used some of my music in his television series Cosmos. My relationships with both NASA and the European Space Agency have been long ones. For me, it was inevitable that I would one day join this scientific world. I have always considered that music is science. Period.”

It should not go unnoticed that 2001’s Mythodea was also inspired by NASA’s Odyssey mission to Mars…

Talk turns from his present to his past, with the imminent arrival, in February, of Delectus. Vangelis famously once stated that when creating music, he acts as a channel through which music is “a bridge from the noise of chaos”. He explains: “I believe that music is implanted in us all and that we have a collective memory.

”If you agree with this theory, which for me is a fact, and if you accept that we have been in some way created by music and we are all part of a collective memory, everything else follows. I do have to make myself clear: I am not talking about the sort of music we hear on the radio, which is only a little branch, but I’m talking about the scientific side of music, which is a tree, a forest and more.”

In a career spanning five decades, initially as a member of the group Aphrodite’s Child and later as a solo artist, Vangelis’ body of work is immense, pushing the limits of available technology to attain levels of creative brilliance that many have tried to emulate, but few have achieved.

“I’ve never felt comfortable with the term ‘career,’” he muses. “I make music every day because it’s been like this all my life and I continue to do so the same way. I have never felt comfortable to be part of the music ‘business.’ For me, ever since my earliest days working with record companies, it has been a means for me to create music on my own terms as much as possible.”

This desire dates back to the time when he first came to public attention as a member of Aphrodite’s Child. The band – also featuring vocalist and bassist Demis Roussos, drummer Loukas Sideras and guitarist Anargyros ‘Silver’ Koulouris – had recorded their first single in 1967 for Philips Records under the name The Papathanassiou Set.

Upon the recommendation of the A&R head of Philips Greece, the band decided to try their luck in England. The chance to explore musical horizons overseas appealed strongly to the four musicians and the decision was made to leave Greece, which was then under a right-wing military coup. As matters transpired, these plans would suffer severe setbacks. Prior to departure, Silver Koulouris received his military call-up papers and was forced to undertake national service. The remaining three musicians had to journey to Western Europe without a guitarist.

They headed to Paris, where, after the resolution of British work permit problems, they found themselves stranded in France due to a nationwide transport strike, the first stages of the French industrial and student unrest of 1968. “The first record contract I ever signed was born out of necessity,” Vangelis recalls.

“Because of all the problems in France at that time, we were stranded and had no money to survive. I couldn’t even call home to Greece to ask for assistance and so I decided to call Mercury Records in France, who offered us a deal. We really didn’t have much choice in the matter and had to sign a contract to survive. As a result, the contract wasn’t at all good, but we became commercially successful.”

Lou Reizner, the record producer and head of Mercury Records’ European operations, suggested that The Papathanassiou Set change their name to the more manageable Aphrodite’s Child. They recorded the single Rain And Tears in May 1968. It would become their biggest worldwide hit. The album End Of The World was released by Mercury Records throughout Europe in October 1968, adorned in a psychedelic sleeve and demonstrating the contrasting commercial and experimental sides of the band. Between 1968 and 1970, Aphrodite’s Child were one of the biggest-selling acts in Europe – but Vangelis was becoming increasingly uncomfortable with the fame and celebrity that went with this success.

We didn’t have a minute to think – we used to do a one-hour programme per day. Frederic Rossif was the first person I’d worked with who realised that spontaneity is the best way to work

“I never understood the phenomenon of celebrity,” he says, waving a hand contemptuously. “I wasn’t interested in being photographed or reading about myself in the newspapers.”

Kolouris returned in 1970, and his arrival coincided with Vangelis’ desire to take the band in a more progressive and experimental direction. This desire would culminate in most of the year being taken up with the writing and recording of a legendary double-album project based on the Apocalypse of St John in the New Testament, with references to the counterculture of the late 1960s and early 1970s. The music on the album 666 would be groundbreaking and stunning in equal measure, but would ultimately lead to the break-up of Aphrodite’s Child before the record’s release.

Today Vangelis still bristles with indignation at Mercury’s initial refusal to release 666. “The company incorrectly perceived the concept to be blasphemous in nature,” he snorts. “They took exception to the piece Infinity on which the Greek actress Irene Papas provided a vocal that, although rapturous and indicative of the times, was not pornographic, as the record company had deemed it. I explained that she was a famous and serious Greek actress and her involvement was also serious.

“It was my first experience of coming across the gulf that exists between the way a record company thinks and the way an artist thinks. The record company said that 666 was not at all commercial and they couldn’t understand what I was trying to achieve.” As a result, it sat in Mercury’s vaults for a year while both label and Vangelis refused to budge.

“When it came to the first anniversary of the completion, I decided to throw a birthday party for the album,” he laughs. “I booked the studio in which we had made the album, bought a big chocolate cake and a candle and invited all of the members of the band, our friends and some journalists to a party where we listened to the album in full. It made a statement!”

The party was also graced by the notable presence of Salvador Dali, who declared the album to be a work of greatness. Finally, due to overwhelming artistic and critical pressure, 666 secured a release in France on the progressive Vertigo label at the end of 1971, where it was hailed as a masterpiece. The release was staggered across Europe, finally appearing in the UK in June 1972, by which time Aphrodite’s Child were no more and Vangelis had begun to collaborate with the acclaimed French documentary maker Frédéric Rossif on his innovative natural history series for French television, L’Apocalypse Des Animaux.

The sounds Vangelis created on the soundtrack score were remarkable, particularly considering no synthesisers were used in the recording process. As a composer who would later become one of the foremost exponents of synthesisers, L’Apocalypse Des Animaux is a fascinating insight into an artist’s ability to create seemingly impossible sounds from any instrument, be it acoustic or electronic.

“At the time I remember that we didn’t have a minute to think,” he recalls. “We used to do a one-hour programme per day. Rossif was the first person I’d worked with who realised that spontaneity is the best way to work. He understood the way I functioned, so he purposely avoided showing me any of the footage in advance of the recording sessions. I was composing and recording while watching the images for the first time.”

Vangelis created the series’ highly evocative music by improvising and performing live while watching projections of Rossif’s images and restricting the use of overdubs to a minimum, an approach he continues to follow to this day. This way of creating soundtrack work was one he found natural. In later years, while scoring music for films that included such major works Chariots Of Fire and Blade Runner, Vangelis never worked to computer-generated time codes to synchronise his music to the picture, preferring to allow directors to edit his music to suit the mood portrayed on screen after he had completed his work.

Vangelis’ first solo album proper, Earth, was conceived and recorded in Paris and released in France and Germany in October 1973. A juxtaposition of primitive and ethnic sounds, combined with progressive rock, the album once more saw Vangelis at odds with his record company.

“At the time of its recording, ethnic music was deemed unfashionable and Vertigo records were uneasy about these influences appearing on any album,” he recalls. “But I followed my instincts and the album was completed.”

Soon after recording Earth, Vangelis made plans to depart France and relocate to England. Signing to RCA Records, he would make London his creative base for the next 13 years, when he would record some of his most famous albums.

I’ve always tried to extract the maximum out of a sound’s behaviour… I can remember as a child putting chains in my parents’ piano just to see how it would affect the sound!

“I entered into recording contracts in the 1970s as a means of funding and building my own studio, to escape the pressures and limitations of recording in sterile commercial studio environments and not to go through the headache of having to book a studio,” he explains. “In other words, a process totally incompatible with the flow of creation. When I built my studio in London, it meant I could create the environment that could make everybody happy and one in which I would be pleased to work in.”

Moving into an apartment in Queen’s Gate, he converted a former photographic studio in Hampden Gurney Street, near Edgware Road, into his creative base. The construction of his new studio, Nemo, continued throughout the closing months of 1974, and work on Vangelis’ first album for RCA began at the beginning of September 1975.

“The surroundings were chaotic while I was making Heaven And Hell,” he reveals, “but all the time I was motivated by the knowledge that I would have the perfect environment in which I could work.”

Released in December 1975, Heaven And Hell is a breathtaking work of ingenuity and musical complexity, dominated by dramatic synthesiser work and stunning choral arrangements featuring the English Chamber Choir. It became Vangelis’ first UK chart album and featured his first collaboration with Yes singer Jon Anderson, who provided a vocal for the song So Long Ago, So Clear.

Anderson had been an admirer of L’Apocalypse Des Animaux and in 1974 he visited Vangelis in Paris. Anderson would later recall: “I heard a track called Creation du Monde from the album and decided that I really had to meet Vangelis. I had seen pictures of Vangelis surrounded by keyboards, with lasers behind him and decided that I really had to meet him. We kept in touch and when Rick Wakeman left Yes, I thought Vangelis would be a great replacement.”

Despite a few initial rehearsals with Yes, Vangelis’ style didn’t gel with the confined format of a group, as he saw it as being too restrictive. However, Anderson and Vangelis would remain in contact. When asked about his experience with Yes, Vangelis declines to comment.

With the completion of Nemo Studios, his creativity exploded. Over the next decade he would record a series of albums that would define and pioneer the worlds of instrumental and electronic music. 1976’s Albedo 0.39, a conceptual work regarded by many as one of his finest, saw him push the perceived boundaries of the synthesiser as a musical instrument to new dimensions, particularly on the spellbinding Pulstar. In addition to synthesisers, the album saw Vangelis utilise a wide variety of other instruments with extraordinary imagination and aplomb.

“I’ve always tried to extract the maximum out of a sound’s behaviour,” he explains. “I think it’s more important to achieve a harmonious result without giving any importance to the source from which a sound originates. I can remember as a child putting chains in my parents’ piano just to see how it would affect the sound! This kind of attitude has always remained with me.”

Vangelis’ music would take on even more dramatic dimensions when he acquired the Yamaha CS-80 touch‑sensitive polyphonic synthesiser, the instrument with which he is most widely associated. The sound would dominate albums such as Spiral, China and his work on the Jon & Vangelis albums, and would inform soundtracks such as Chariots Of Fire and Blade Runner.

“For me the CS-80 is the greatest synthesiser ever made,” he enthuses. “It’s the most important synthesiser in my career and the best analogue synthesiser design there has ever been. It was a brilliant instrument, though unfortunately not a very successful one. It needs a lot of practice if you want to be able to play it properly, and because of the way the keyboard works, it’s quite a hard instrument to master. But at the same time, it’s the only synthesiser I could describe as being a real instrument, mainly because of these characteristics. I went to great lengths to obtain one. It’s such a good instrument, I still use it in my studio today.”

It was following China that Vangelis and Jon Anderson finally worked together in an official capacity. The collaboration began as three weeks of improvisational and informal recording sessions in February 1979. The sessions weren’t undertaken with any specific project in mind, simply for the amusement of both musicians, but when Anderson quit Yes at the beginning of 1980, things moved on apace.

After reviewing the recordings, it was decided that they could be the basis for a potential album. Final production work was completed and, in January 1980, Short Stories by Jon & Vangelis was released. I Hear You Now, the first single, became a hit, which in turn made Short Stories an equal success. The partnership would see the release of two further albums in the 1980s: The Friends Of Mr Cairo and Private Collection. There was a hit single with I’ll Find My Way Home from the former album, whose State Of Independence also became a hit for Donna Summer when she released her version of the song in 1982, produced by Quincy Jones.

My studio in Paris was remarkable, because the walls and ceiling were glass… playing while being able to see the moon and the stars, the birds flying and the seasons change was wonderful

Today it’s clear that Vangelis has mixed feelings about these albums. “Although there were hit singles and so on, I was very uncomfortable about participating in all the promotion that such success demanded,” he states. “I didn’t enjoy appearing on shows like Top Of The Pops. I was very uneasy with it. At the same time I am fond of pieces such as Horizon [the side-long piece on Private Collection].”

The early 1980s would also see Vangelis reaching new heights as a film soundtrack composer. His 1981 soundtrack to Hugh Hudson’s film Chariots Of Fire, set around the 1924 Olympic Games in Paris, is one of the all-time defining motion picture scores. The entire score and the Titles movement in particular have become synonymous with the spirit of the Olympic movement.

Hudson’s original intention had been to use L’Enfant from Vangelis’ soundtrack album Opéra Sauvage for the film’s opening sequence, but was persuaded that a newly written piece would be better suited to the images. “I didn’t want to do period music,” he recalls. “I wanted to compose something that was both contemporary and still fitting with the imagery and feel of the film.”

Subsequently, Chariots Of Fire won Vangelis an Academy Award for Best Original Score in 1981. The single Titles and the album became huge international successes. “It’s very rewarding for me to know that through the years, the music seems to have given, and still does, so much pleasure and a feeling of optimism to so many people around the world.”

Such success led to an increase in soundtrack work, most notably in 1982 when he was commissioned to provide the score for Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner, and Japanese director Koreyoshi Kurahara’s Antarctica.

“I always have an instinctive approach, similar to the way I create all of my music,” he says. “The difference with a film score is that a film has an idea, has a story and has a construction, with a definite beginning and a definite end. Within these conditions I have to sail, but I’m sailing being guided by my first immediate impression when seeing the images and without reading the script, in order to avoid as much as possible having any preconceived ideas around what I’m watching.”

Such success wasn’t without its pitfalls, and following the release of Soil Festivities (1984), the choral Mask and the avant‑garde Invisible Connections (both 1985), the artist once again found himself at loggerheads with his record label, echoing his frustrations with Aphrodite’s Child.

“I’ve never created music according to the music industry’s pattern and language of releasing an album, making a promotional video and so on,” Vangelis sighs. “With this pattern, according to a record contract, you can’t release more than one or a maximum of two albums a year. This seems to me to be a wrong attitude and unfortunately I have been through that process.

“The majority of the music I write had nothing to do with the pattern of record companies. As far as the music industry is concerned, any release is always a commercial decision. As for me, making music is not the result of any particular decision. I’ve always been interested in all musical forms.”

Vangelis departed London in 1987, eventually relocating to Paris in the early 1990s, building a new studio in the city to accommodate his own unique requirements. “My studio in Paris was remarkable, because the walls and ceiling were glass. I was told by some people that this was a crazy idea and that glass would not create a good acoustic environment, but I’ve always had crazy ideas, and the sound we had there was fantastic. The feeling of playing while being able to see the moon and the stars above you, or the sun rise, or to see the birds flying and the seasons change was wonderful.”

It was in these stunning surroundings that Vangelis would produce many of his latter-day works: the elegiac soundtrack to 1492: Conquest Of Paradise and more recent studio albums such as Voices (1995), Oceanic (1996) and El Greco (1998).

He remains as inspired and creative as ever, now working from the studio in his Paris home where he created Rosetta. Yet he remains torn between the commercial world of the music industry and his own work, which comes from an artistic muse. The conflict within is all too evident.“Since I began my relations with what we call the music industry, what distracts and depresses me the most is the absence of any musical sense between the business side and the artistic side,” he muses. “The music industry grew massively over the years, having the sole target of making money, using disrespectfully the most sacred and divine gift we have, which is music.

“Music has the ability to become the perfect channel to transfer positive or negative forces. During the last 40 years, music is often used by the industry to carry quite negative and dangerous forces. The question that arises out of that is that if music is such a perfect carrier, why does the industry not use it for positive and healthy purposes?

”For me the answer is simple: the other road is a huge generator of money due to careless usage of this force, combined with the egocentric and narcissistic approach from many artists. The music industry is a centre of culture, but that culture is bankrupt. Fortunately, there are positive exceptions in every genre and in musicians all over the world.

“As far as I am concerned, I missed the opportunity to be happy and relaxed when I had to deal with much of the music industry. Nevertheless, I have to say that during my recording career I have met some honest, caring and responsible people from both the industry side and the artistic side. Regardless of the music industry, I will always be inspired by the things around me and will continue to create music because it’s most natural thing for me to do.”