The chief prosecutor of the International Criminal Court (ICC), Karim Khan, controversially applied for arrest warrants to be issued for top Israeli and Hamas officials on May 20. He has accused them of bearing criminal responsibility for war crimes and crimes against humanity committed during the Hamas-led October 7 attacks and Israel’s subsequent assault on Gaza.

The move has been praised by human rights groups as well as countries including France and South Africa. By contrast, it has outraged the leaders of other countries such as the US and the UK.

Israel’s defence minister, Yoav Gallant, has rejected the arrest warrants sought for him and the prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, saying Khan had drawn a “despicable” parallel between Israel and Hamas. At the same time, Hamas said it denounced the decision to “equate the victim with the executioner”.

The responses of Israeli and Hamas leaders to the announcement are perhaps understandable. But more puzzling is why other political leaders do not support the ICC’s attempt to bring justice to traumatised victims.

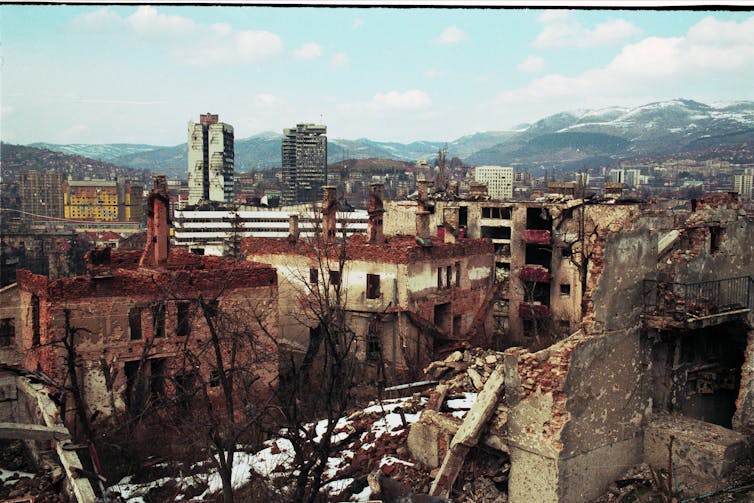

In the past, other institutions such as the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY), which was established by the UN to prosecute the war crimes that had been committed during the Yugoslav wars (1991–2001), have met with a similar mixed response. This is linked to the so-called “peace versus justice” dilemma. One of the assumptions here is that if political and military leaders are indicted before a peace agreement has been reached, then their incentives to enter negotiations may be reduced.

Once an agreement has been reached, its implementation is also often still dependent on the cooperation of the military and political leaders involved. If they have been threatened with prosecution, then this cooperation might be lost.

Drawing on the experiences of the ICTY and its impact on peace and justice in Kosovo and in Bosnia and Herzegovina, what are some of the possible benefits and pitfalls of Khan’s recent indictments if the ICC’s judges decide to support them?

Delivering justice

The ICC only intervenes when it concludes that national courts are unable or unwilling to prosecute war criminals. According to Amnesty International, the independence of the Palestinian judicial system has been undermined by presidential decrees that have appointed favoured officials throughout governmental and judicial institutions in the West Bank.

And the Israeli judicial system is not willing to prosecute the leaders of Israel. In fact, rights groups say that Israeli authorities routinely fail to fully investigate violence against Palestinians.

Given this, the ICC appears to be the only way of potentially initiating the long process of establishing accountability. This was also the case for the ICTY.

The ICTY only managed to indict 161 people responsible for war crimes in Yugoslavia – and sentenced just 90 of them. But this did include notorious political and military leaders such as Radovan Karadžić and Ratko Mladić. The ICTY convicted both Karadžić and Mladić for their roles in the 1995 Srebrenica genocide, where more than 8,000 Bosniak Muslim men and boys were killed.

In the subsequent years, the ICTY also supported local legal proceedings in Kosovo and Bosnia and Herzegovina. In Kosovo, three people have been found guilty, two trials are ongoing, and two cases are at the pre-trial stage. And in Bosnia and Herzegovina, 644 cases involving 978 defendants were completed between 2004 and 2021.

Progress has since slowed. As of July 2023, 237 war crime cases against 502 defendants were still pending. But the fact that war criminals are still being brought to justice – albeit slowly – indicates that Khan’s request could spearhead a justice process that eventually includes national courts, once the current regimes have been replaced and the peace-building process solidified. This would deliver justice to more Palestinian and Israeli victims than the ICC can do on its own.

One of the greatest threats to the ICTY’s credibility was criticism that the tribunal indicted many more Serbs than it did Croats and Bosniaks. But, by including leaders from both parties in the same request, Khan has indicated that the ICC is committed to prosecuting perpetrators and bringing justice to victims regardless of the side they belong to. This should hopefully add to the ICC’s credibility.

Undermining peace

Khan’s request has been met with anger from some political leaders partly because they think it could jeopardise the chances of eventually bringing peace to the region. In a similar way, many initially saw the ICTY’s indictment of Karadžić and Mladić in Bosnia and Herzegovina as a threat to the fragile peace-building process.

So, despite many opportunities, the international peacekeeping force in former Yugoslavia took years to arrest many of the military and political leaders that the ICTY wanted to prosecute. Karadžić and Mladić were not arrested until 2008 and 2011 respectively, despite both being indicted in July 1995.

This undermined not only the credibility of the ICTY, but also that of the international peacekeeping operation, which was heavily criticised for not supporting the ICTY.

The test case in former Yugoslavia suggests that early attempts to establish justice may inadvertently complicate the peace-building process. It is unclear whether this will also be the case in Israel and Palestine.

Majbritt Lyck-Bowen does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.