Flexi schools cater to young people who have been pushed out of mainstream schools. Some students may have been expelled or struggled to fit in. Some may have been bullied or have learning needs the mainstream system could not meet.

Flexi schools give students a second (and sometimes a third, fourth or fifth) chance to stay or become engaged with schooling.

Demand for flexi schools has been increasing, but we still have little information about the quality of schooling young people receive at these schools, or their long-term trajectories after attending one.

Our new research shows students value the support they get from their flexi school but want the curriculum to challenge them more, and better support their aspirations.

What are flexi schools?

Flexi schools come in multiple forms. Some sit alongside mainstream government high schools. Some are run by community groups, church organisations or are backed by philanthropy.

There is limited recent data on how many flexi schools there are in Australia. A 2014 report estimated 70,000 young Australians were engaged in flexi schools. This number is expected to be higher in 2022. This report was published almost a decade ago now and the sector was predicted to grow because of the demand.

Flexi schools tend to be smaller than mainstream schools, often with fewer than 200 students. They are centred on the young person, their needs, strengths and interests. There is an emphasis on community, relationships and wellbeing. Schools usually don’t require students to wear a uniform and it is common for a student to call their teacher by their first name.

We surveyed almost 500 flexi school students around the country in May to June this year. This is the most comprehensive picture of young people’s experiences in flexi schools in Australia to date.

Flexi school students are diverse

Our research showed Australian flexi schools educate a diverse group of young people. The average age of a student is 15 years old, with ages ranging from ten to 20 years. Our respondents came from 43 different cultural backgrounds. One in three identified as Aboriginal and or Torres Strait Islander.

In such a diverse school setting, 77% of young people said they felt their identity was valued. More than 80% felt their flexi school was a welcoming place. As one respondent said:

If I am experiencing issues, teachers support me, don’t judge and are extremely kind and considerate.

Flexi school students have high aspirations

Many flexi school students have already been labelled as “disengaged” by the sheer fact mainstream schooling hasn’t worked for or accommodated them. But this does not mean they are disengaged from their education or their lives going forward.

In our survey we asked young people to tell us about their career and life goals. Young people told us they had a huge range of career goals from owning a small business to doing a trade or becoming a park ranger, youth worker, primary teacher, author or worker in the mining industry.

Our respondents told us they have have strong aspirations for their futures. As one student told us:

[I want] to grow my [business] into a popular […] local gardening landscaping service supporting houses and gardens that need repairing.

Others told us they want to become “totally independent” and talked about pursuing happiness and community connections:

[I want to] find some work I purely enjoy and just live a normal life. Preferably doing some trade work or contributing to the community.

Young people also specifically spoke about doing further study and going to TAFE or university, to do a wide range of courses from computer science to education and medicine:

I aspire to be a paramedic or doctor when the time comes, I would like to go to university to study medicine.

Flexi students want to be challenged

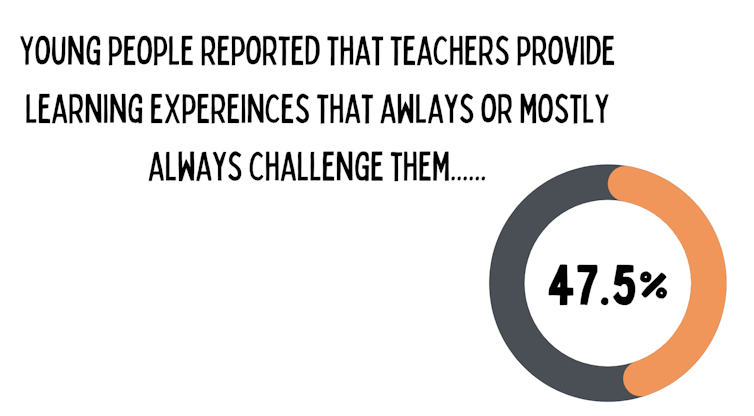

It is often assumed young people in flexi schools are not interested in doing intellectually challenging work. Data from our survey shows this is not the case.

Less than half (47.5%) of the young people we surveyed said they experienced learning that was challenging. They told us they wanted “harder work, more future guidance” and “more learning at my age level”:

I learn best when I am given a challenge and have help to understand the challenge when I don’t understand what to do.

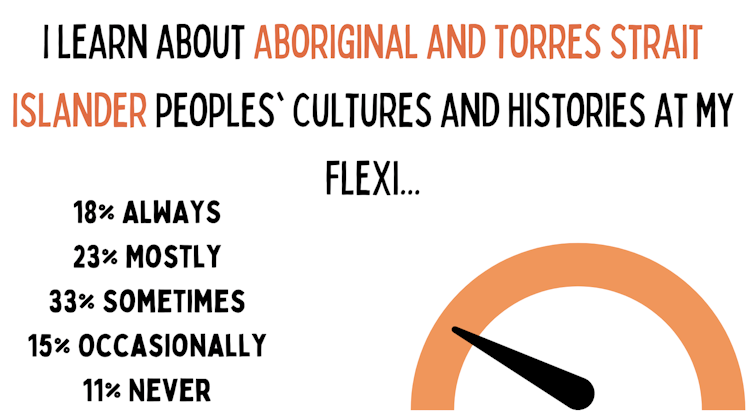

When we asked young people what they would like to learn at their flexi school they said more STEM-related subjects (including maths, science, coding and engineering), history and geography, social studies and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Cultures. As one student wrote:

Access to learn more about Indigenous culture and access to learn another language !!! (like Auslan for example)

Our respondents were also keen to learn more about life skills, wellbeing, and vocational education.

There is a lot policy makers, educational leaders and practitioners in flexi schools can learn from this finding. Flexi schools are not just about keeping young people “in school”. They also need to provide a high-quality curriculum and challenging, diverse learning experiences.

The bigger picture

In an ideal world, there would be no need for flexi schools because mainstream schools would cater for every young person in society. This is not the current reality and in the meantime, flexi schools play a critical role supporting young people who would otherwise be disengaged from mainstream schools.

Read more: Personalised learning is billed as the 'future' of schooling: what is it and could it work?

Flexi schools need to respond to young people who have diverse needs. The focus tends to be on their relationships and wellbeing. But young people have told us they want a challenging curriculum as well.

As a matter of social justice, young people need a curriculum that adequately equips them for life and further study or training. This is an issue flexi school providers and policy makers must consider as a priority.

Marnee Shay receives funding from the Australian Research Council and Edmund Rice Education Australia.

Jodie Miller receives funding from Edmund Rice Education Australia.

Martin Mills receives funding from the Australian Research Council and from Edmund Rice Education Australia.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.