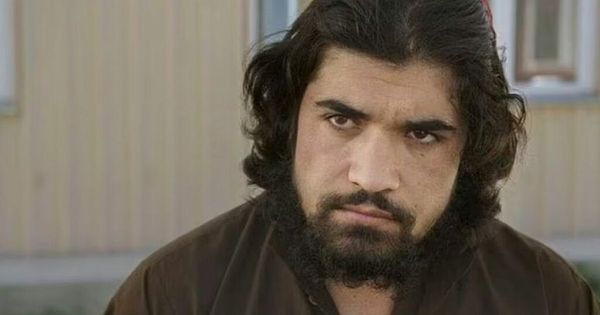

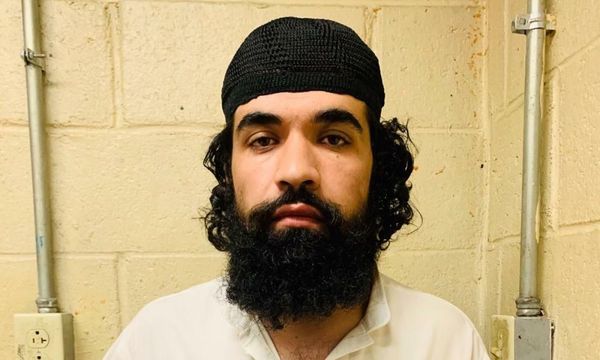

Hekmatullah, the rogue Afghan soldier who killed three unarmed Australian diggers in Afghanistan a decade ago, is living in a luxury home in the capital Kabul, treated as a “returning hero” by the Taliban who released him from prison.

He has said he does not regret killing Australian soldiers, and has vowed he would again kill Australians, or anyone who opposes the Taliban.

“If I am released I will continue killing foreigners,” Hekmatullah told an official of the former Afghan government when his release was being negotiated.

“I will continue killing Australians and I will kill you as well because you are a puppet of foreigners,” he said.

“I am among my brothers, we will be free, Afghanistan will be free. We will kill you.”

Since returning to Afghanistan, Hekmatullah has reportedly been housed in the former diplomatic quarter of Wazir Akbar Khan. He lives in a heavily secured property in a district adjacent to the clandestine former home of Ayman al-Zawahiri, the former al-Qaida leader assassinated eight days ago by a US drone strike as he stood on the balcony of his villa.

Hekmatullah’s release from prison in 2020 was fiercely resisted by Australia, with the government previously conceding it did not know where he had been since being freed.

Of 5,000 prisoners the Taliban wanted released as part of peace deal negotiations with the US, Hekmatullah was one of six terrorists that western governments fiercely resisted being pardoned, because they had either killed unarmed foreign nationals, were unrepentant about their crimes, or had vowed to commit further acts of violent terrorism.

A former senior official in the democratically elected government of Afghanistan – overthrown in August 2021 – has confirmed to the Guardian Hekmatullah’s return to Afghanistan.

“He was welcomed back to Kabul as a hero … with a house, car, guards, an amnesty for his crimes, his expenses are being paid for. He is being treated as a hero.”

The Guardian has independently confirmed Hekmatullah’s repatriation to Afghanistan. Family members of the Australian soldiers killed have said they have not been updated on his whereabouts.

On 29 August 2012, at Wahab, a patrol base in Afghanistan’s Uruzgan province, Hekmatullah, then an Afghan National Army sergeant, drew his M16 and fired more than 30 rounds from close range at Australian troops. He killed three: L/Cpl Stjepan Milosevic, 40, Spr James Martin, 21, and Pte Robert Poate, 23.

Hekmatullah fled the base into the Baluchi valley and was designated a “high-value” target for the Australian SAS in Afghanistan within 24 hours. He was the sole target of a controversial SAS mission to the village of Darwan in Uruzgan province on 11 September 2012, based on – ultimately flawed – intelligence he was hiding in the village.

The mission was the subject of extensive evidence presented during the long-running defamation trial brought by the former SAS corporal Ben Roberts-Smith, who denies all wrongdoing in relation to an allegation he participated in the murder of an Afghan national during that mission.

Two other Australian SAS soldiers have also been accused of unlawfully killing Afghan nationals during the raid – allegations they deny.

It was not until February 2013 that Hekmatullah was arrested after being found hiding in Pakistan’s lawless border region. Charged, tried and convicted of three counts of murder, Hekmatullah was sentenced to death, but served only seven years in Bagram prison before being moved to Qatar in 2020, where he lived under house arrest.

After the fall of Kabul to the Taliban, he returned to Afghanistan, where he now lives in Kabul.

The senior former government source said he insisted to senior government officials that Hekmatullah not be released, because he presented an ongoing danger, but objections to his release were overruled because of a US desire to conclude its 2020 peace agreement with the Taliban.

“The person I met is a dangerous terrorist, a dangerous man,” the source said. “He is not repentant, not regretful. He is a threat, he can cause harm to the world. He should not have been released.”

The source said Hekmatullah appeared to be “very well protected”, with close links to senior Taliban officials now in government.

“But the Taliban who hold the strongest grudges, who want to take revenge, are those who were in prison, including him, Hekmatullah. He has hatred still.”

The release of the 5,000 Taliban prisoners was the subject of fierce and fractious debate during negotiations between the US and representatives of the terror networks in Qatar.

The US-led Coalition objected to 200 of the prisoners because of the nature of their crimes – green-on-blue attacks, or attacking civilian targets – or because they were seen to be ongoing terror threats. Hekmatullah was among the 200.

After further negotiations, the list of objections was reduced to 15: Hekmatullah was still on the list. After still more talks, the list of objections was just six names. Hekmatullah remained still, deemed unsuitable for release.

In August 2020, then prime minister Scott Morrison said he spoke directly with then US president Donald Trump, urging that Hekmatullah remain imprisoned.

Hekmatullah, Morrison said, was “responsible for murdering three Australians and our position is that he should never be released”.

But the US overruled Australia’s objections, arguing the release of terrorist prisoners, while unpopular, would lead to a “reduction of violence and direct talks resulting in a peace agreement and an end to the war” in Afghanistan.

Australia’s department of foreign affairs and trade declined to answer questions on Hekmatullah.

The anonymous previous-government source told the Guardian former officials who remain in Afghanistan face the grave threat of retribution from the Taliban.

“The Taliban is seeking revenge: they have no mercy. We will be identified soon. Our lives, and the lives of our families, are in danger.”

He said the US assassination of al-Zawahiri, the former al-Qaeda leader, had escalated tensions – and heightened Taliban security fears – dramatically.

“The world is definitely putting pressure on the Taliban for appearances. But no matter how much pressure is put on the Taliban, they put pressure on the people.” Those who worked for the former democratically elected government have “been left on the battlefield … as enemies of the Taliban”, he said.

A Human Rights Watch report this month said Taliban forces had summarily executed or forcibly disappeared more than 100 former police and intelligence officers in four provinces since taking over the country in August 2021, in defiance of a proclaimed amnesty.

“Summary killings and enforced disappearances have taken place despite the Taliban’s announced amnesty for former government civilian and military officials, and reassurances from the Taliban leadership that they would hold their forces accountable for violations of the amnesty order,” the report said.

“The Taliban, through their intelligence operations and access to employment records that the former government left behind, have identified new targets for arrest and execution.”