With chalk-white lips and his head now bald, Alexander Litvinenko slumped against a pillow, a hospital gown around his chest, and told the world he thought he’d been poisoned.

As the former Russian spy’s story broke and that iconic image appeared on front pages, Dr Jim Down, a young consultant at London’s University College Hospitals ’ ICU, tried to figure out if this mysterious patient in side room nine could possibly be right.

Back in November 2006, when Litvinenko, 43 – an ex-employee of KGB successor the Federal Security Service and now a Kremlin critic in the pay of MI6 – arrived on the ward vomiting and rapidly losing weight and hair, Jim was part of the team treating him.

It also fell to Jim to break the news of his death after three cardiac arrests to Litvinenko’s wife Marina and son Anatoly, then 12.

Yet he still had no clue what had killed the spy until later that night, when radioactive polonium-210 finally showed up in tests.

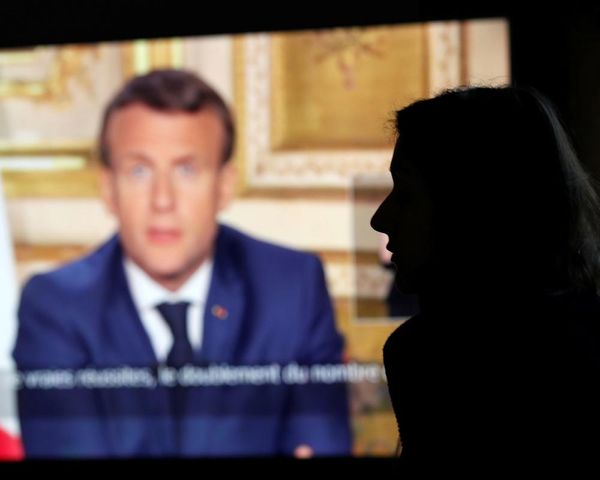

It was later discovered Litvinenko had probably drunk a poisoned cup of tea at a London hotel, allegedly at the hands of former Russian agents under Vladimir Putin ’s orders – although Russia denies any involvement. A four-part ITV drama called Litvinenko, starring David Tennant, that started on Monday, charts the sinister events which unfolded.

Jim reveals after learning the cause, he was sworn to secrecy by a Miss Marple-type figure from the Health Protection Agency, who arrived in ICU with her own flask of tea. There was no allowance for the fact he was fearing for his own exposure, plus that of his team, including pregnant nurses.

“The initial stress was he had died, it was very high profile, he was a young man, and I didn’t know why,” Jim recalls of that nightmarish time. “And yes, I wondered if I was at risk. I had so little understanding of how much was a significant dose. I didn’t think I was going to die of acute radiation poisoning, but I wondered if I might be at increased risk of leukaemia in 10, 20 years.”

Because of the secrecy demands, he and the hospital didn’t reveal the truth to staff immediately, and Jim now believes a better approach could have been taken.

For three days after Litvinenko’s death, his body was in lockdown in ICU as investigators frantically trawled London following his last movements. When staff heard the word polonium on the news, they were terrified.

“I think the lesson I learnt was what my responsibility is,” Jim reflects. “There were conflicting priorities. This was a big incident and there was a whole public health concern around London. But my responsibility is to the patients and staff.”

Although Litvinenko had been given a massive dose of the chemical which meant he didn’t stand a chance, measures confirmed the staff were not at risk.

But providing vivid insight into the episode in his memoir, Life in the Balance: A Doctor’s Stories of Intensive Care, Jim captures those immediate fears.

“Resuscitation is chaotic and messy, so multiple members of staff had come into contact with his body fluids,” he writes.

“He had vomited into the face of the doctor who’d put the breathing tube down into his lungs. Would that vomit have contained polonium? And, if so, how much? And how much was too much?

“The nurses had handled his urine, sweat and blood. Could we be sure that they’d not been put at risk? They had a right to know.”

Yet despite the intrigue that swirled around him, Jim remembers Litvinenko as being “calm” before he lost consciousness.

“I only met him awake once and I remember this incredible stoicism. He had a presence and bravery,” he recalls.

“He seemed resigned to the fact he had been poisoned and seemed to feel he would not survive.” He recalls Marina was the same when he broke the news of Litvinenko’s death.

“I think she knew it was coming,” he says.

Of that most bizarre chapter in his career, he explains he was as much in the dark as anyone. “I was watching his interviews like everyone else but treating him at the same time,” he says. “In the ICU, there were so many people – normal police officers but also counter terrorism officers, too, I think. I remember it was when Spooks was very big on TV and I imagined them to be like the cast of Spooks.”

The consultant of critical care and anaesthesia, now 52, has remained at the hospital and came to public prominence during the Covid-19 pandemic when BBC crews interviewed him during a report which brought us some of the first images from inside a Covid-stricken ICU.

Jim, a married dad of twins, was shown in PPE amid disturbing scenes.

He now admits he was pushed to breakdown by the summer of 2021 by the sheer scale of the disaster.

Traumatised, and triggered by the death of a complex patient unconnected to the virus, his anxiety became overwhelming.

Thankfully, he asked for help and today admits openly that he still takes an anti-depressant and sees a psychiatrist.

“I felt awful, but I didn’t feel like I didn’t want to get better,” he stresses.

Jim was sent to the site of the Hatfield rail crash in 2000, treating victims amid the carnage. He also treated those caught in the July 7 London bombings in 2005, describing one young survivor particularly graphically in his memoir. “Her lower limbs had taken the full force of the blast and were a mangled mess of tendons, muscle and skin,” he writes.

“It became apparent that someone else’s foot was embedded in her thigh.”

Yet none of it compared to the massive onslaught of Covid, which saw a usual 30 critically ill ICU patients jump to 120 of “the most sick, difficult patients we have ever looked after,” Jim recalls.

He held iPads so dying patients could say goodbye to their families when Covid restrictions banned face-to-face contact.

At the time he was unable to visit his late mother, who had dementia, in her care home. So his reaction towards Boris Johnson’s Partygate scandal is predictable.

“The fact people making the rules and asking people to do extraordinary things weren’t following them… that makes one angry,” he says, carefully.

Now he faces a new level of strain amid a beleaguered NHS. Nurse walkouts and forthcoming junior doctor strikes impact his work. He explains: “The bit we see most acutely in ICU is we are always balancing emergency admissions with admissions for elective surgery. We have to now spend some money, retain our staff by treating them properly. Particularly after the pandemic, we really appreciate our colleagues.”

He knows, as well as any of them, the sacrifices that were made.

* Life in the Balance: A Doctor’s Stories of Intensive Care by Jim Down (RRP £18.99)