Back in the day, when he was the drummer for a heavy metal band, Frank Hall was everyone’s friend. And Frank has a story for every occasion. He was there back in the 70s when Ozzy Osbourne – whom he calls John, “because it’s his real name” – took a shotgun to his chickens in a drunken stupor. “He’d just got back from America. I was staying at his house. I was in bed and I heard this ‘bang, bang, bang’. Bloody woke me up. He set fire to some stables, too. He said they were full of rats. I don’t know what gets into John.”

Hall was the man John Bonham gave his drum kit to. “It was a Ludwig kit with the green sparkle. I said: ‘I wish I had one of those.’ Next thing I know we’re driving down to Bonham’s farm in a Range Rover and shoving it in the back.”

He mixed with Thin Lizzy (“Phil was Phil, he was always looking for the next bird”), Keith Moon (“This one time Moony was playing my drums, and I’m looking at him, thinking: ‘He’s terrible, he can’t play”), and Kray twins associates Chris and Tony Lambrianou (“I wasn’t bothered what I said around them – they knew all I wanted to be was a drummer”).

Today, Hall is a healthy 60-something, and as friendly as you’d expect a man who mingled with rock stars and criminals to be. A hereditary muscle-wasting condition means he spends much of his time in a wheelchair. “Doesn’t stop me drumming, though. There’s no muscle in my calf, but I can play flat out for three hours solid.”

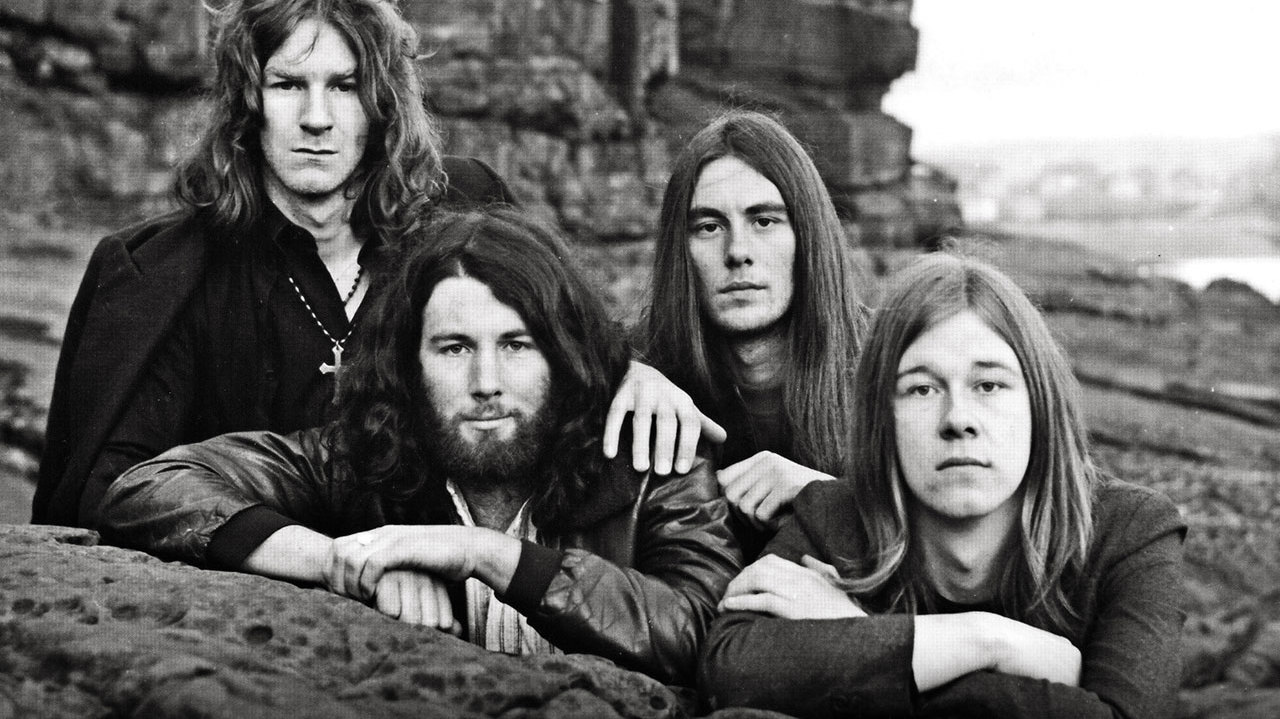

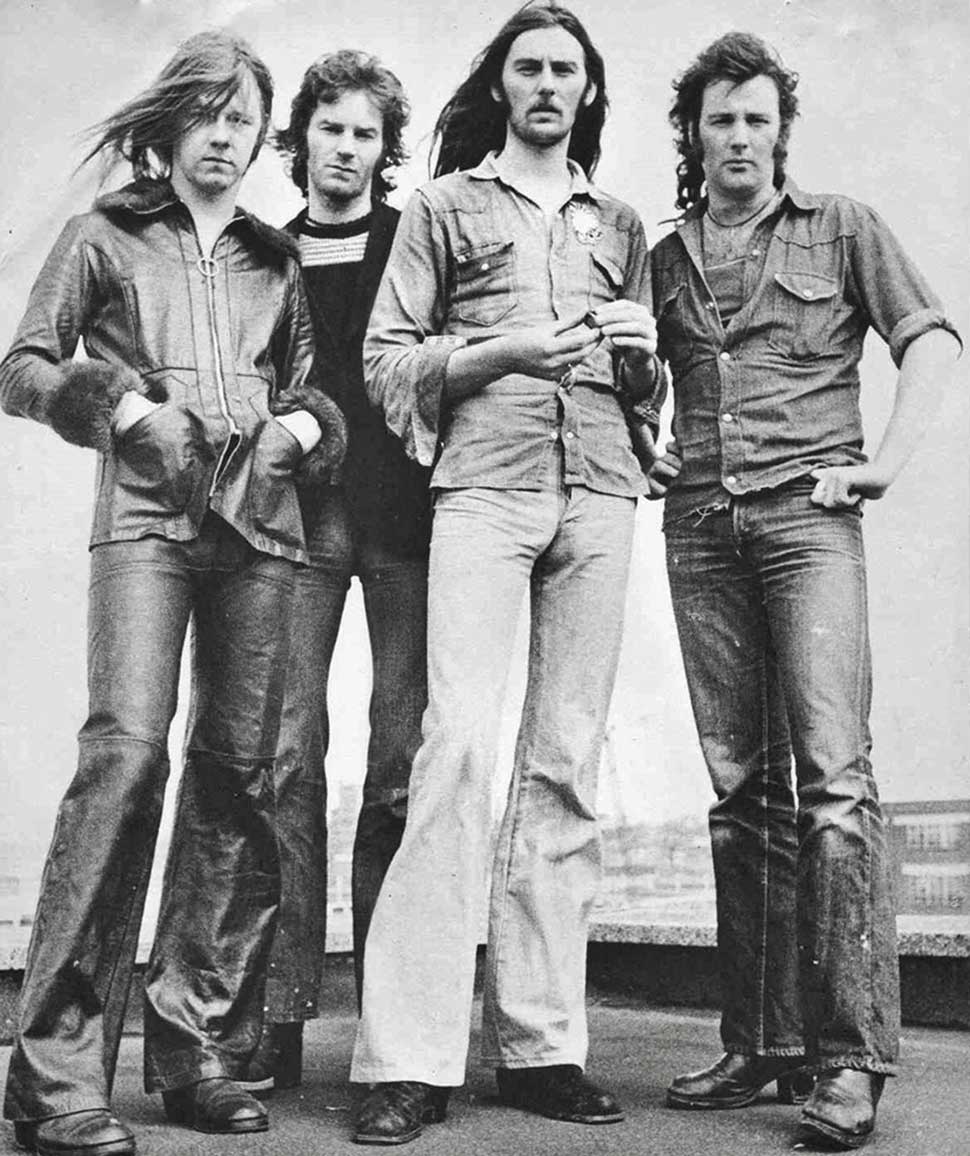

But 45 years ago, Hall was on the verge of something big. His band, Necromandus, were earmarked as the next Black Sabbath – by Black Sabbath themselves. They didn’t quite have it all, but they had a lot, including Tony Iommi as a manager and, in guitarist Barry Dunnery, one of the great lost six-string geniuses of heavy metal’s golden age.

Except Necromandus never became famous. They never even got to release an album. Frank Hall might have a story for everyone else, but he’s got his own story too: one marked by bad luck, poor timing and unfulfilled dreams. Until now.

Necromandus were part of the second wave of British heavy metal: those kids who picked up the ball from Sabbath, Cream, Zeppelin and Purple and ran with it. Their songs had a whiff of prog rock and even jazz cutting through the spliff smoke. Melody Maker called them “Black Sabbath playing Yes’s greatest hits”.

Necromandus’s history is tightly bound with that of Sabbath. It was at a gig by Iommi and Bill Ward’s pre-Sabbath outfit Mythology in Cockermouth that Hall saw the light. “I’d never seen anything like it. I’d never seen a left-handed guitarist before. And Bill was knocking seven bells out of John Bonham.”

They stayed in touch. Mythology mutated into Earth and then into Black Sabbath, picking up Geezer Butler and Ozzy along the way. “I met John at a sound-check,” says Hall of the latter. “He didn’t have any shoes on, he was a right state. And he was rude. Rude and pissed. But he had stage presence.”

The connection paid off. Frank watched Sabbath’s star rise as he tried to get his own career off the ground. When his first band, Heaven, fell apart, he tapped up Barry Dunnery, who was making his name on the local scene with his band Jug. “I hitched to Egremont,” Hall says, “knocked on Baz’s door: ‘Do you fancy being in a band?’ He said: ‘Are you any good?’ I said: ‘We can be.’”

They were joined by singer Bill Branch and bassist Dennis McCarten, but Dunnery was the secret weapon. He was a classic early-70s guitarist, one who could switch between heavy riffing and jazzy chops in a heartbeat. Hall recalls the band sound-checking for a gig at the Marquee. Across the room, two men stared at Barry, agog. “It was Steve Howe from Yes and the bass player, the big lad who died [Chris Squire]. Baz was doing all this Allan Holdsworth legato stuff. Steve Howe was pointing at him, going: ‘How the hell is this kid doing that?’”

But there was a darker side to Dunnery. One day, in the back of the band’s van, he confided to Hall: “I have this weird feeling in my head.” He suffered from crippling anxiety attacks. Hall suspects they may have been a product of undiagnosed depression; mental health wasn’t high on the agenda in the world of early-70s heavy metal.

“Baz always wore a big scarf,” says Hall. “As soon as I saw the scarf tightening up in his hands, I knew there was something wrong with him. He used to call me ‘kid’ – ‘Kid, come here and chat’ – because he knew I wouldn’t take the piss out of whatever it was that was wrong with him. At that time, geezers didn’t tell other geezers: ‘I’m suffering with me nerves.’”

Dunnery’s problems took a back seat to the band’s career – a career that got a boost when their old friend Tony Iommi offered to manage them. Their day-to-day business was overseen by Sabbath associate Wilf Pine. Pine had one foot in the music industry and one foot in the crime industry. He was friends with Sabbath and Zeppelin, and also with the big London gangs and even the New York mafia.

“Wilf was a good bloke to know,” says Hall. “People were frightened of him and his mates. They used to turn up in Rollers and Lamborghinis, no visible means of income other than frightening people to death.”

Iommi decided that Cumbria was too far away from the action and, in 1972, moved Necromandus to a house in Birmingham. During that time they regularly supported Sabbath. Another local band, Judas Priest, opened for them.

It was Iommi who engineered a deal with Vertigo Records and shepherded the band into Morgan Studios in North London to record their debut album, with Rod Stewart producer Mike Butcher. They were on what Hall calls “the poor shift” – nine at night until three or four in the morning – but they didn’t care. “It was the first time we’d ever been in a studio,” says Hall. “We didn’t even know half the stuff in there existed.”

Yes were in Morgan at the same time. Hall remembers wandering into a room as Rick Wakeman played his new solo album, The Six Wives Of Henry VIII, on one of the studio’s reel-to-reels. “He didn’t know me from Adam,” says Hall. “But I said to him, really cheeky: ‘We’ve got a track called Leaving The Depot, but it needs a piano or a Mellotron. Can you do it for us?’ He said: ‘Yes. Could you go as far as a crate of Guinness for payment?’”

Wakeman never did appear on the album, but Iommi added a few licks here and there. The finished article, titled Necromandus, was a slab of classic early-70s heavy rock, impressively complex and brutally simple at the same time. At its best, as on the mooted lead-off single Don’t Look Down Frank, they sounded as good as their mentors Black Sabbath. There was just one hitch: the album was never released. On the eve of an American tour supporting Black Sabbath, Barry Dunnery walked out on Necromandus.

“Baz wouldn’t do the tour. He couldn’t fly. Just couldn’t get on a plane,” says Hall. “He didn’t tell anybody. He just left. Never came back. But I knew there was something wrong. Maybe he was in a deep depression at the time. We were living hand-to-mouth, nicking potatoes from restaurants to eat. Baz kept saying: ‘I can’t live like this.’ It wasn’t if he was going to leave, it was when.”

Dunnery’s departure marked the end of Necromandus. Having lost their MVP, Vertigo shelved the album. Hall asked Tony Iommi, whose attention was being diverted by Sabbath’s Stateside success and looking after Ozzy, if they should carry on. “Only if you can get another guitarist as good as him,” replied Iommi.

That wasn’t going to happen, and Hall knew it.

Necromandus may have been finished, but it’s far from the end of Hall’s bottomless well of stories. Here’s another: a few years later, in 1976, a Range Rover pulled up outside his house. Out got an old friend from Cumbria who worked for Ozzy. “Ozzy’s been kicked out of Sabbath,” said the friend. “He wants to put a band together with you, Baz and Dennis.”

Hall all but rolls his eyes as he says this. He knew what Ozzy was like, and knew just how much of a pain in the arse he would be to work with. But he had nothing to lose. So Hall, McCarten and Dunnery – who was playing music again with Hall in local bands – decamped to Bullrush Cottage, Ozzy’s rural home in Staffordshire. They were the original Blizzard Of Ozz, the band who would kick‑start Ozzy’s solo career and maybe get their own back on the rails. At least that was the plan.

A typical day at Bullrush cottage was chaotic. “We’d wait for him to get up, which was around three in the afternoon: [Ozzy impression]: ‘’Ello man, whaddya want to do?” You’d think: ‘For fuck’s sake, John,’ and try to sober him up.”

This meant shoving him in the shower. “He’d come out wrapped in towels and collapse on the floor. Then he’d go: ‘Thelma, what time do they open?’ And then he’d go up to the Hand & Cleaver and come back at nine o’clock, out of it.”

They managed to pull it together for long enough to start working on songs. “Baz was writing new songs. But the stuff that was coming out of us was prog rock. You can’t imagine Ozzy singing prog rock. God knows where them recordings went. He probably lost them when he went down the pub.”

Everyone knew it wasn’t going to pan out, but Hall didn’t want to bail on his old mate – even when he got a call from his mum. “She said: ‘Phil’s drum tech just called to find out where you are and what you’re doing.’ I didn’t knew who she meant when she said Phil. I thought she meant someone from Whitehaven.”

Phil was Phil Collins, who had recently stepped up to replace Peter Gabriel at the mic in Genesis and needed a replacement for himself in turn. Hall says: “I was torn between Ozzy and Genesis. ‘What the hell do I do?’ We’re putting this together with Ozzy, even though it was dropping to bits cos he’s an alcoholic and up-your‑nose freak.’”

Loyalty won out. “I turned down Genesis. I reckon I would have been in with a shout of getting it. I had the chops.”

Soon afterwards, the Blizzard Of Ozz fell apart. Ozzy returned to Black Sabbath, and Hall, McCarten and Dunnery went back to Cumbria, their last shot at the big time gone. Frank played with a couple of NWOBHM-era bands, Hammerhead and Plateau, then moved to London in the mid-80s, where he covered AC/DC songs in a band with future Slade singer Mal McNulty.

Dunnery joined ELO offshoot Violinksi, playing on their 1979 hit single Clog Dance, before history repeated itself. On the eve of an overseas tour, he bailed once more.

Necromandus became a long-vanished speck in the rear-view mirror of history, leaving Hall to dine out on tales of the famous people he had known. Except his own story was far from done.

Never underestimate the doggedness of the fanatic. The Necromandus flame died down, but it was never extinguished, kept flickering down the years by bootleggers, crate-diggers and heavy metal historians. Dodgy copies of the album they had recorded back in the early 70s could be found if you knew where to look. The bootlegs had different names, depending on where you found it: Quicksand Dreams or Orexis Of Death. The songs had been renamed too, in order to avoid paying publishing royalties. “Me mam first told me about it in about 1995,” says Hall. “I’d never heard of it before. I was excited and annoyed.”

The album was finally released legitimately in 2005. A few years later it got a reissue via Rise Above Records. By then, Hall was the last surviving member of Necromandus. Bill Branch died in 1995, Dennis McCarten in 2010. Brilliant Barry Dunnery passed away in 2008.

But there’s still at least one more chapter left in the story of Necromandus. Enter Tom Tyson, a local producer who has worked with Albert Lee and former ELO violinist Mik Kaminski, among others. Tyson knew Necromandus when he was growing up, just as everybody in the north-east did. He’d worked with the four members separately over the years. “I always wanted to get Necromandus back together,” he says today. “They were one of the greatest, most unique bands of their time.”

A couple of years ago, Hall asked Tyson to help out on some music he was making and maybe resurrect the Necromandus name. “How can we put it back together when there’s nobody left except the drummer?” Tyson wondered. “That’s when we brought the others into it.”

He helped Frank build a brand new band, bringing in keyboard player John Marcangelo and Bill Branch’s soundalike son, John, as vocalist. Slowly they pieced together a new album, titled Necromandus, just like its ill-fated predecessor.

The new album is released this month. It’s a fitting a tribute to the original band and a fine record in its own right. Some of the tracks feature guitar from Barry Dunnery, salvaged from an old rehearsal tape. Hall and Tom Tyson aren’t saying which tracks. “It was really emotional when Tom said: ‘Get up here and listen to this,’” says Hall. “It was like he was there in the room with us.”

After decades in the wilderness, Hall has got the bug again. Or maybe he just never lost it. With Tyson’s help, the band have four songs ready for a new album that the producer says could be “ready in six months”. They’re thinking of asking Rick Wakeman to appear on it again. “Dunno if he’ll want a crate of Guinness this time,” says Hall.

At this point it’s traditional to ask a musician if they have any regrets. The stock answer is “None at all” or “I wouldn’t change a thing”. Not Frank Hall. “Yeah, all the missed opportunities,” he says. “I knew deep down inside that it wasn’t going to work with Baz. He couldn’t help what was wrong with him. He didn’t really understand it. But I wish I had done other things, like gone for Genesis.”

The missed opportunities and vanished dreams will always be there. But so will the stories. And the story of Necromandus – and Frank Hall himself – sits right up there alongside them.

This feature was originally published in August 2017, in Classic Rock #239.