From 2005 to 2014, I had the honor and privilege of playing alongside Dickey Betts in his band, Great Southern. Sharing the stage with Dickey for a decade constitutes some of the greatest musical experiences of my life, and it was truly a blessing to get to know him and call him a friend.

Dickey was a giant, universally revered as one of the greatest guitarists of all time. He possessed a purely distinct signature style and sound that was uniquely his own, distinguished by an ingenious blend of blues, rock, country, Western swing and Appalachian string music, delivered with the touch, tone and technique of a true virtuoso.

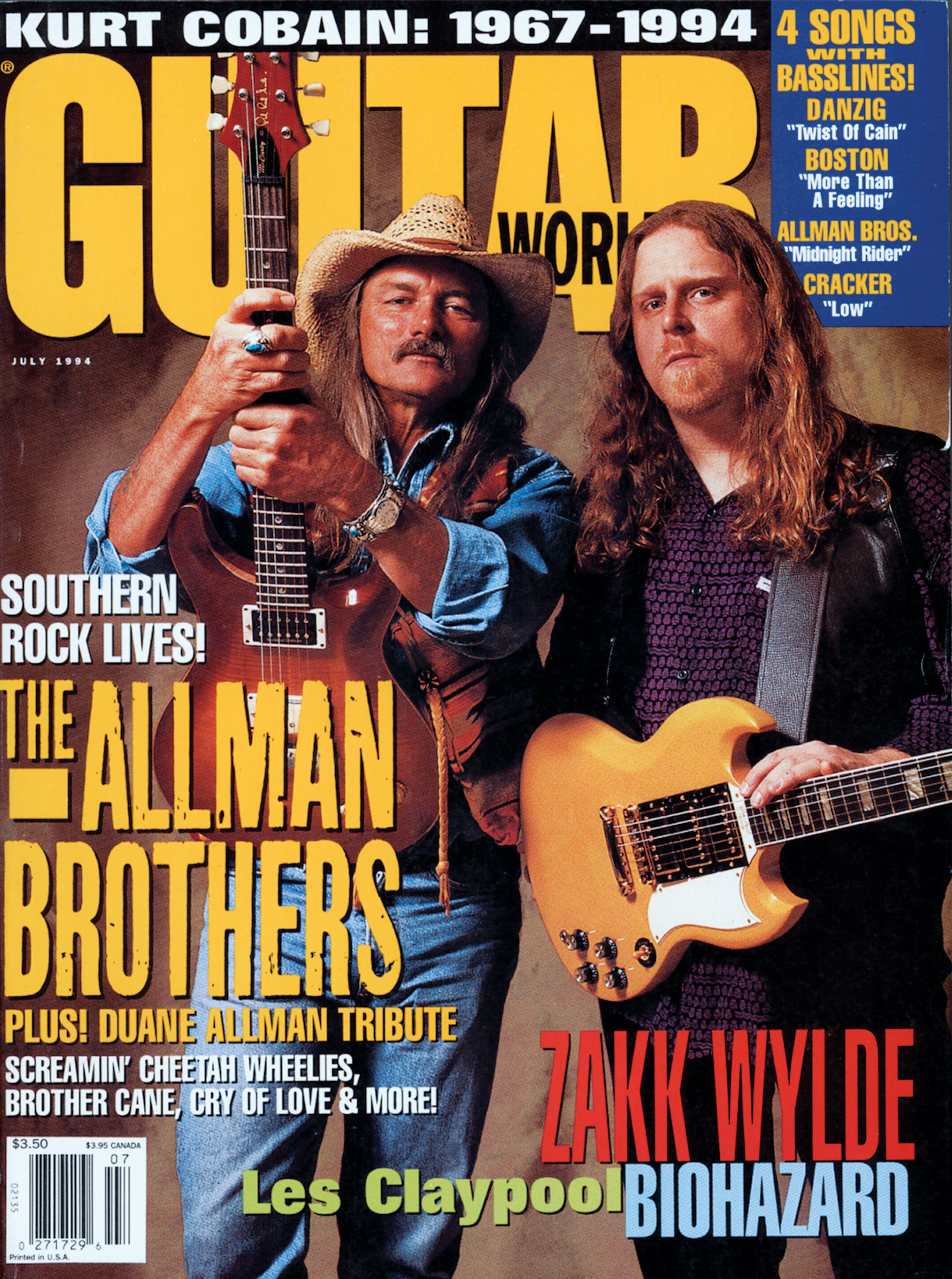

As one of the founding members of the Allman Brothers Band, Dickey, via his phenomenal playing and brilliant songwriting, laid the foundation for what was at the time a new style of music to be known as Southern rock.

He and his co-guitarist, Duane Allman, weaved intricate harmonized guitar parts unlike any ever heard before; prime examples of these beautifully intricate harmonized lines are at the heart of songs such as Blue Sky, Revival, In Memory of Elizabeth Reed and many others. Betts’ impact on generations of guitarists, as well as all musicians and the broad spectrum of American music, is immeasurable.

During my 10 years as Dickey’s guitarist, we played upwards of 250 shows across the globe. We traversed the U.S. many times and traveled to Japan and performed in Germany, Poland and Spain on numerous occasions. As one might imagine, there’s a flood of great memories from all of the shows and events shared over the years. My journeys with Dickey Betts taught me more about performing, and about life, than all of the years leading up to that point.

Betts has long been one of my favorite guitarists. I fell in love with his playing from my initiation to the Allman Brothers Band’s music via their classic 1971 double live album, At Fillmore East.

As an aspiring 15-year-old guitarist at the time, I remember hearing Statesboro Blues on a New York FM radio station, kicked off by the classic spoken introduction, “Ok, the Allman Brothers Band!” and Duane Allman’s laser-like slide guitar playing.

I had just started to play slide, and when I heard Statesboro, it inspired me to sit down in earnest to get it together, doing my best to learn every one of Duane’s slide solos, along with every single Duane and Dickey solo on the entire album. 30 years later, this dedicated study would pay off in ways I never could’ve imagined.

As a longtime writer for guitar magazines, I’d had the opportunity to interview, play with and become friends with many of my guitar heroes, including Johnny Winter, Buddy Guy, B.B. King, Jeff Beck, Albert King, John McLaughlin and others. As of 2001, Dickey Betts had not been one of them.

During the ’90s, Allman Brothers’ guitarist Warren Haynes had become a friend, and throughout that time I found myself backstage at many Allman Brothers shows at the Beacon Theatre in New York City.

There were a handful of times when I was within a few feet of Dickey; he’d always be sitting in a chair off the side of the stage, apart from everyone else, most definitely “in his own space.” His vibe was that he wanted to be left alone, and I respected the impression he gave.

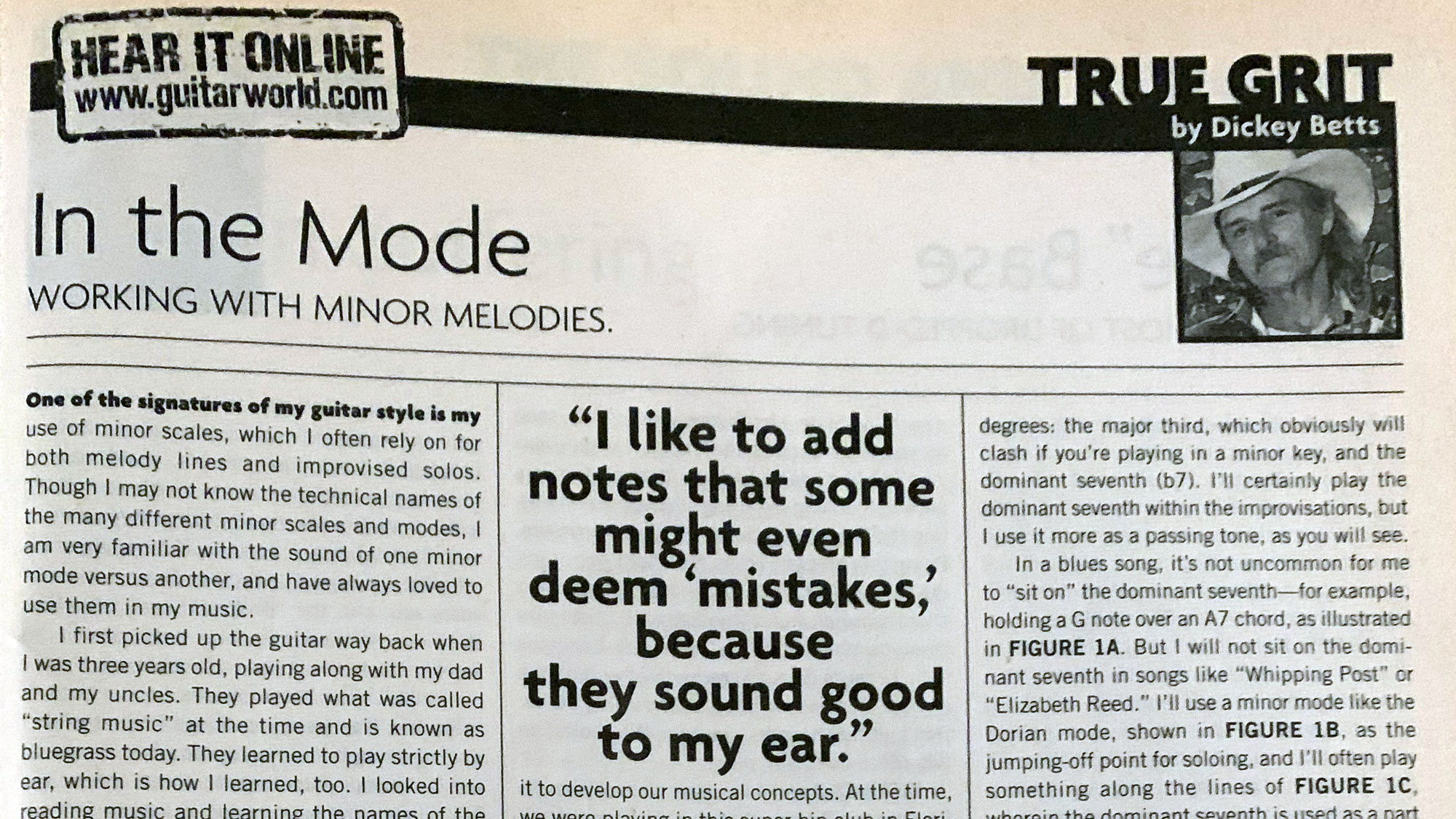

In 2000, Dickey was unceremoniously “released” – fired – from the Allman Brothers Band. Stories abounded on both sides with a lot of negative statements made. Guitar World Editor-in-Chief Brad Tolinski thought it would be a good idea to offer Dickey a monthly column in the magazine, as it would afford him the opportunity to speak directly to his many fans around the world. I began working with Dickey on his column, called True Grit, which ultimately ran for more than a year and a half.

The lessons were a big hit with the readers, as each month he’d use the space to teach and discuss his most beloved songs, such as In Memory of Elizabeth Reed, Blue Sky, Jessica and Ramblin’ Man. Readers could see how deep-thinking and eloquent Betts was, as he spoke at length about the roots of his playing, which began at the age of five, when he played guitar alongside his violin-playing father and uncles.

The family’s musical heritage originated from Prince Edward Sound in Nova Scotia, and this very distinct style can be found in indigenous Acadian recordings from more than 100 years ago. Elements of the unique melodic nature of this music served to lay the groundwork for Dickey’s original and beautifully melodic soloing style on the guitar.

“An important element in the formation of my style is that my dad was a fiddle player, and I grew up surrounded by all of those great bluegrass fiddle melodies,” Dickey said.

“My dad was very into precision; he was a cabinet maker, and every nail had to be driven just right. He was the same way about music: the fiddle had to be tuned perfectly, and he played with the same precise approach.

One day, I said, “Dickey, it would be great to sit in with you some time if the opportunity arises…” He said, “Any show you can make, call my stage manager Mike, and he will make sure there is a half-stack Marshall waiting for you”

“All of those beautiful Irish folk melodies of the fiddle had an impact on me early on, which I didn’t even realize until I started trying to find my own voice on the guitar. The strong sense of melody I inherited from him had been deeply instilled in me.

“That’s when I began to search for a strong sense of melody within the blues form, which I think is a good overall characterization of my style. One of the best examples of this influence coming to the fore is Jessica.”

In putting the articles together, Dickey and I would speak at length on the phone. One day, I said to him, “Dickey, it would be great to sit in with you some time if the opportunity arises.” His response was unexpected; he said, “Any show you can make, call my stage manager Mike, and he will make sure there is a half-stack Marshall waiting for you.” No-one had ever made such a generous offer to me.

For the next three years, if Dickey had a show within 100 miles, I made sure I was there. Between 2002 and 2005, I sat in with Dickey and the band more than 20 times.

For most people, Betts was a bit of an enigma. His reputation as a hell raiser was well earned, and there’s no way anyone could know what he was like on a personal level. He was definitely mercurial, but he was also one of the sweetest and most generous people you could ever meet. And his sense of humor was tremendous.

In 2003, before I joined the band, he invited me down to his house to celebrate his birthday with him and his family. It was a nice gathering, with one of his daughters and his grandchildren; I was the only non-family member there.

It was a tall task to learn all of the intricate harmonized guitar parts for Dickey's entire three-hour show, and I had about two days to do it

At one point I went outside to call my wife, and within a few minutes, the door opened and there was Dickey with a plate and a big piece of birthday cake. He said, “I was looking for you! Don’t you want some of my cake?”

One morning in 2005, while I was standing in line at the bank, Dickey called and said, “Hey, listen – my guitar player just quit and the tour starts in a week. Do you want to do it?” At that time I had a full-time job with Guitar World, writing for five different magazines, plus two young kids at home. So I said, “Yes, definitely! When do you want me to come down?” He said, “Right now!”

It was a tall task to learn all of the intricate harmonized guitar parts for Dickey's entire three-hour show, and I had about two days to do it. His sets included some of his most difficult material, such as High Falls, Nobody Knows, True Gravity, Jessica, Nothing You Can Do, Revival and so many others – almost all of the material from the Allman Brothers records as well as the Great Southern records and new songs, too. I transcribed reams of charts and brought them with me, and from the very first rehearsal, we were off to the races.

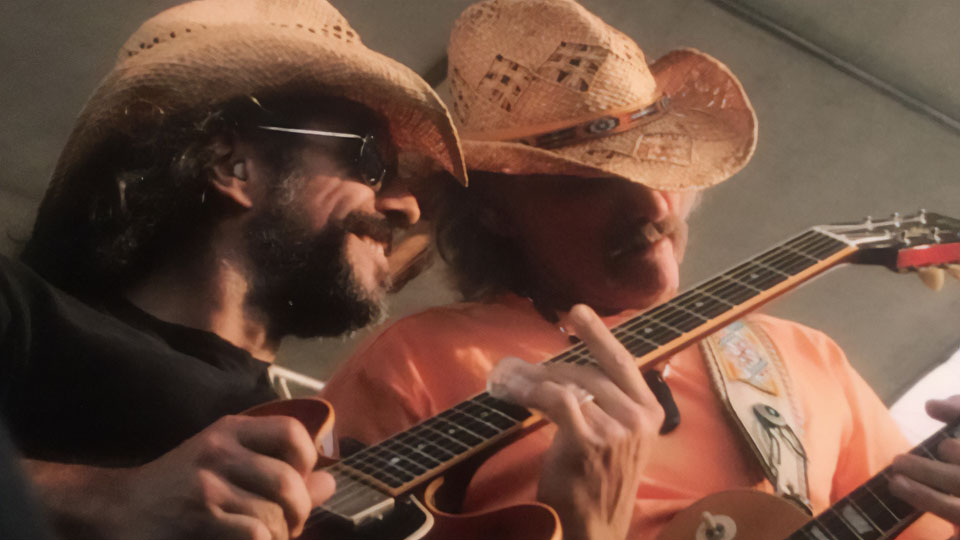

At our very first show, a private event at B.B. King’s Blues Club & Grill in New York City, I went up onstage before sound check to plug in and get the sound together. Dickey came out, stood next to me, plugged in and said, “Let’s play High Falls together.”

As we started to play the opening harmonized lines, he stopped and said, “You should play the parts a little more delicately. Think of our guitars harmonizing in the same way that the Everly Brothers sing.” It was such a beautiful way to describe the sound he was looking for, and I knew immediately what he meant. That one piece of advice changed the entire way I looked at playing harmonized parts with him for all of the songs.

I’ve been asked many times what it was like to work with Dickey. He was a great artist, and as such was very sensitive to every aspect of the music and the contributions of each member of the band.

He could be very impressionistic in his descriptions of what he was looking for. For example, for the last section of the final harmonized lines in Jessica, he said, “For this part, imagine leaves falling gently in the breeze, drifting back and forth as they drop down from the sky.” It was such a beautifully clear image, such a great mindset to have, and we all understood the nature of the sound he wanted.

On the first tour, we spent a lot of time sitting together on the bus, and he would talk about his feelings regarding leaving the Allman Brothers Band. He often became very emotional about it.

The music of the band he helped create, and the relationship between the band and the audience, meant everything in the world to him. There was a lot of frustration.

But he would never say anything negative about anyone in the band. He always referred to Gregg Allman as “Gregory,” and he would say, “Gregory is one of the greatest singers I have ever heard. The man has a golden voice.”

I used Duane Allman’s slide for every gig for the next six years

In 2011, we had just returned from a Rock Legends cruise and were sitting in his music room – it was just Dickey, his guitar tech Carlos Rodriquez and me. We were talking about songs to add to the set, and I said, “People always ask for Pony Boy; it’s such a great tune.” Dickey said, “Oh, I played that on an acoustic resonator guitar, and I don’t think I even remember how to play it.”

He then picked up a resonator guitar that was next to him and proceeded to play the intricate slide guitar part of Pony Boy… perfectly. It appeared to be absolutely effortless. Carlos and I had our jaws on the ground.

He then looked at me and said, “I gave you one of Duane’s slides, right?” I said, “No, you did not!” He walked to the other room and within a few minutes came back holding out a glass Coricidin bottle.

He said, “I could only find one — here you go.” I said, ”Don’t give it to me if you only have one!” He said, “There are some others here somewhere. You don’t have to use it if you don’t want to.” I said, “Yes, I most definitely want to.” I used Duane Allman’s slide for every gig for the next six years.

Dickey was a complex person. He was very passionate about music and could be intense about what he wanted and expected from the band. Dickey set the bar very high and led by example. These are the things that made him who he was and made him such a great bandleader. He wanted and expected everyone to play their best, even better than they thought they could. The result was that everyone’s level of musicianship grew by leaps and bounds.

I am forever indebted to Dickey Betts for the opportunity to play with him and spend time with him. He blessed the world with his incredible music, and his great legacy will be celebrated for decades to come.